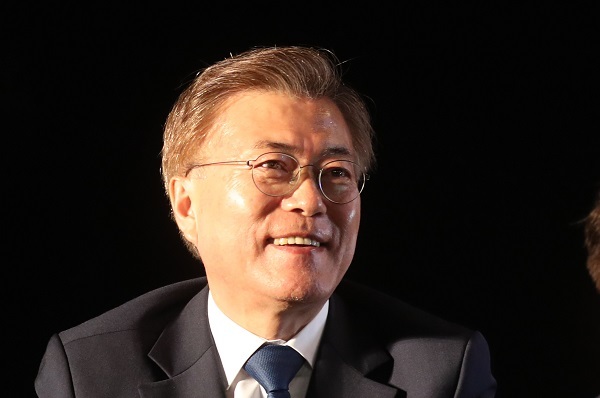

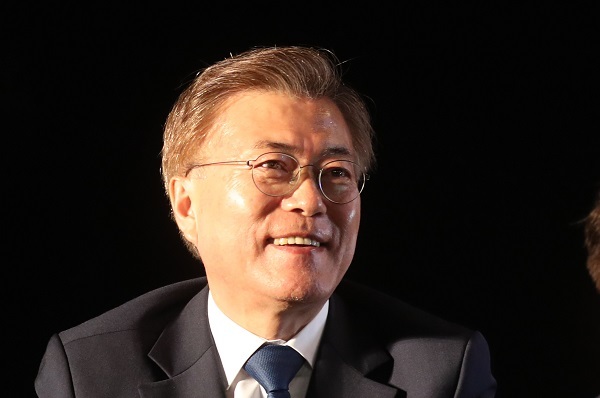

President Moon Jae-in faces an uphill battle in navigating through a bleaker-than-ever diplomatic security landscape with diminishing strategic space in the face of North Korea’s rapidly evolving threats.

Fresh off the grueling snap election, he now has to rapidly switch gears as the new commander in chief to manage the volatile situation on the peninsula while regrouping institutions that have been in tatters in the wake of his predecessor Park Geun-hye’s impeachment.

|

President Moon Jae-in (Yonhap) |

Moon, who served in top posts in the Roo Moo-hyun administration, is widely expected to return to the late liberal leader’s approach of pursuing greater political and economic cooperation with the North and greater balance between the US and China.

The old playbook, however, has grown far more difficult to practice than read over the past 10 years.

Having detonated a fifth nuclear device last year, Pyongyang claims to be on the brink of mastering the technology for an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of striking the US mainland. Washington, faced with what appeared a looming sixth test last month, floated military action and staged a series of show of force. China, a top partner in trade, investment and tourism and a key stakeholder in multilateral talks aimed at disarming the North, has been taking crushing economic retaliation over Seoul’s decision to host the US’ Terminal High Altitude Area Defense system. Following a brief letup, relations with Tokyo have been strained yet again over a girl statue that signifies Korean women forced into sex slavery during World War II.

And a perhaps more explosive feature in the game is that Moon is encircled by a league of leaders who assert their respective agenda like no other -- take Kim Jong-un of North Korea, Donald Trump of the US, Xi Jinping of China and Shinzo Abe of Japan.

If Moon moves to carry through contentious election pledges like a restart of the inter-Korean Kaesong industrial park without adequate coordination, he may well face headwinds from not only the US and other neighbors, but also the public and opposition camp wary of security threats. His Democratic Party of Korea holds only 120 seats in the 300-strong National Assembly, whereas the far-right Liberty Party Korea is on course to jack up its slice to 106 seats. The center-left People’s Party has 40 and the conservative Bareun Party controls 20 seats.

“Given that North Korea’s nuclear and missile threats are much more advanced than in the past and it claims to be a nuclear weapons state, the public sentiment would not be so favorable if the new government disregards this and pursues dialogue and exchanges with the North,” said Kim Hyun-wook, a professor at the Korea National Diplomatic Academy in Seoul.

“First and foremost it would be vital to coordinate policy and cooperate with the US, which takes the lead in the nuclear and missile issues, in order to respond better to North Korean threats.”

Moon-Trump chemistry

In an interview with The Korea Herald last month, Moon said South Korea should “take the lead” on peninsular issues, instead of being a “spectator” wishing the US and China luck in their talks.

While calling Kim Jong-un an “irrational” leader and Trump a “savvy businessman,” the candidate pledged to engage in direct negotiations with the former on the nuclear problem and strike a better deal with the latter than others would have done otherwise.

|

US President Donald Trump (Yonhap) |

Analysts say the top priority for the Moon government is to foster rapport with Trump, while formulating its own recipe for tackling the nuclear conundrum, one that is meticulously thought-out yet has room for maneuver.

As Seoul has grappled with the political turmoil and leadership vacuum, the Trump administration embarked on a North Korea policy overhaul and consulted it with China and Japan through summits.

Critics have pointed out that South Korea may be losing its voice in a discussion in which it has the biggest stake. The concerns were fueled further by Trump’s recent demand Seoul pay $1 billion for the THAAD battery.

“The monthslong leadership void incurred substantial diplomatic damage, and now it’s imperative to bring it back to normal,” said Kim Yeol-soo, a professor in political science and foreign affairs at Sungshin Women’s University in Seoul.

He stressed the need for an early summit with Trump, where Moon could lay the groundwork for an “emotional bond” and mutual policy understanding. There are some lessons from Abe who has apparently managed to give an impression he could help shore up the US economy and create jobs in line with Trump’s “American First” mantra, while infusing Tokyo’s stance on the sex slavery rows with Seoul, Kim said.

“We are in the middle of the global pressure and sanctions campaign against North Korea, so any move to resume Kaesong or Geumgangsan tours would spell serious trouble for the new government,” the professor said.

“What’s more urgent is to put US ties back on track and then hold summits with Japan and China, such as on the margins of the Group of 20 summit (in Hamburg, Germany), rather than rush to mend the tense inter-Korean relationship.”

Park Ihn-hwi, an international studies professor at Ewha Womans University in Seoul, echoed the view, but emphasized that Seoul should be armed with its own, concrete North Korea policy before dealing with Trump.

As part of his election promises, Moon said he would resolve the nuclear issues through a “step-by-step, comprehensive approach” that blends sanctions and denuclearization negotiations. It is intended to start with a moratorium on all nuclear activities and then progress to a complete closure of the program, which would also entail an inter-Korean military mechanism and a peace treaty.

“Whether it be on sanctions or dialogue, it’s essential to build exquisite logic with which to confront both the US and China and solicit people’s support at home,” Park told The Korea Herald.

“Without that, the new leadership will yet again fail to maintain balance between the two superpowers, and the society will remain divided over foreign policy.”

THAAD dilemma

In the election campaign’s final stretch, the surprise deployment of key THAAD parts and Trump’s bombshell demand for payment was seen as an unexpected boost for Moon, who has said the next administration should overhaul the issue “from square one.”

Now in office, the president has to make the final call, but this time the once favorable factors could prove more vexing than he may have expected.

|

(Yonhap) |

The transport of a radar, launchers and other core components of THAAD to Seongju, North Gyeongsang Province, took place in the early hours of April 26, inciting protests from residents and other activists. Trump’s payment remarks came the following week.

The developments appear to have tilted the scale, hardening the position of not only the public, but also Moon himself.

As speculation surged over North Korea’s sixth nuclear test and military tension with the US flared up last month, Moon’s on-the-fence stance on THAAD became a source of criticism from other contenders. The souring sentiment eventually led him to say in an interview with the Chosun Ilbo daily that he would have no option but to press ahead with the deployment to counter Pyongyang’s continuing nuclear provocations and military buildup.

But following the payment controversy, he returned to his initial reserved stance, criticizing the former government for rushing through the deployment.

Voters have also grown more skeptical. In a recent poll by Research and Research, nearly two-thirds of respondents said the next government should renegotiate the THAAD deployment or its terms with the US.

In contrast, a Gallup Korea poll conducted in mid-January showed 51 percent of those surveyed were in favor of the deployment. Last summer, the figure reached nearly 56 percent.

As an election pledge, Moon vowed to seek the National Assembly’s approval for the THAAD installment, which would likely pass under the current seat composition. Yet it could also risk criticism the measure was to evade his own responsibility amid spiraling controversy.

“I think that once it is put to a vote, it wouldn’t be difficult to pass because there are lots of conservative and centrist lawmakers who support it,” a diplomatic source said, requesting anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter.

“By winning the parliamentary endorsement, the next government may secure some legitimacy in continuing the deployment, but it will have to present its own position in one way or another before sending it to the floor, so no free lunch most likely.”

Choi Jong-kun, an international relations specialist who has been advising Moon, said the new leadership will conduct a comprehensive “review” on THAAD.

“It’s a matter of adjustment and legality, not concessions,” he said in an interview with The Korea Herald, referring to the involvement of the Status of Forces Agreement, on which the two countries have already agreed terms for the deployment.

“For President Moon, it’s no tricky issue because the assembly will decide as a legal process of the democratic country and a constitutional requirement. Of course, he may have a preference but would take a prudent, constructive attitude so that the cost issues don’t hijack all alliance issues,” said Choi, a professor in political science and international studies at Yonsei University in Seoul.

Historical tension with Japan

The president is also tasked with balancing territorial and historical disputes and a security partnership with Japan.

Moon has vowed to renegotiate the December 2015 settlement, which drew robust backlash from victims and the public alike. “It’s unacceptable. In line with the view of the majority of the people, it must be renegotiated,” he said in an interview with The Korea Herald, calling the settlement “wrong” in terms of both content and process in the run-up to the announcement.

|

A statue memorializing wartime sex slaves in South Korea (Yonhap) |

More recently, Seoul and Tokyo have engaged in another string of spats over a new statue memorializing wartime sex slaves and Tokyo’s renewed claim to the Korean islets of Dokdo.

Tokyo has been protesting a new memorial set up by civic groups in December in front of the Japanese consulate-general in Busan, saying it runs counter to the accord that says it will work to “properly resolve” the statue issue via consultations with related organizations. In January, Japan recalled its Ambassador to Seoul Yasumasa Nagamine and Busan Consul-General Yasuhiro Morimoto, only to return them last week, and declared a moratorium in negotiations over a bilateral currency swap deal designed to stabilize the Korean currency in a time of financial crisis.

“Given the complexity and sensitivity of the comfort women issues, the new government needs to separate its approach toward historical and security issues,” Kim of Sungshin Women’s University said, calling for a summit with Abe to promote understanding.

By Shin Hyon-hee (

heeshin@heraldcorp.com) and Yeo Jun-suk (jasonyeo@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)