ASTANA, Kazakhstan -- Hurriedly taking turns with his wife to feed their hyperactive 1-year-old son, Alexander Lee seemed restless, yet happy to be consumed by his family.

I met Lee, a reporter at Kazakh TV of Korean ethnicity, at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s summit in Astana in June, when I covered several key events at the time as a journalist. When I came back to Astana for a second time in late August, he was one of the first people I got in touch with.

“I moved here in 2011 after living in many cities around the world, and I can see a lot of changes that have taken place over the last seven years. Astana changes every day, every week, every month and every year,” he told me at a family restaurant a stone’s throw from the glistening landmark Bayterek Tower in downtown Astana, Kazakhstan’s sleek new capital.

“The city’s outlook constantly evolves with new buildings, people and events. Recent additions include a Ferris wheel and an aqua park with swimming pools for children and families. But the most important change happens in the mentality of people that live here,” he added.

|

Visitors at Expo 2017 Astana in Kazakhstan take part in an interactive activity at the Nur Alem Kazakh Pavilion in the center of the expo site in late August. (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

The Expo 2017 Astana on the outskirts of the city -- themed on future energy -- received positive reviews from the New York Times, the Economist and other prominent media outlets for its informative, engaging programs and architectural innovations. (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

Astana, a stylish administrative capital bisected by the Ishim River in northern Kazakhstan, is a city thriving on the myriad dreams and yearnings of its 1 million citizens.

Dotted with swank new buildings designed by world-class architects, wide boulevards and fresh greeneries in between -- juxtaposed by clearheaded urban planning -- Astana in many ways feels like Toronto, where I lived for 13 years as a Korean-Canadian before moving to Seoul.

“Astana is a young capital still trying to find its own niche in the international arena,” Lee explained, adding most of its residents have come from other cities and regions over the last 20 years since 1997, when it was designated the nation’s capital. The name “Astana” means “capital city” in Kazakh.

“Living here requires a new mentality, a new consciousness and ethos of being a law-abiding citizen. The city is a concoction of different mentalities, habits and traditions, a multicultural melting pot,” according to Lee.

|

Downtown Astana is strewn with iconic landmarks and skyscrapers, most notably the Bayterek Tower. (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

Downtown Astana is strewn with iconic landmarks and skyscrapers, most notably the Bayterek Tower. (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

As an example, those who drove their cars fast and furiously in the countryside eventually learn to be docile, even genteel behind the wheel in Astana, he said. “To me, this represents the ultimate progress that Astana and the larger Kazakhstan are going through. It isn’t simply about some pretty new buildings. When the people’s mindset is changing, that’s the most important thing for the nation.”

Notwithstanding the new urban culture, Astana was marvelous enough with its nonpareil architecture. Aside from the Bayterek Tower in the city center, one shining landmark is the Khan Shatyr Entertainment Center, a giant transparent tent designed by British architectural firm Foster and Partners in a uniquely neofuturist style. The 150-meter-tall tent has a 200-meter elliptical base spanning 140,000 square meters, with many shopping and entertainment facilities including a water park with an artificial beach, a children’s playground and 37-meter drop tower.

The Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, also designed by Foster and Partners, is another exotic edifice built in the shape of a pyramid. It was constructed to host the Congress of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions, and houses a 1,300-seat opera house, museum of culture, library, research center and futuristic convention halls.

The Hazret Sultan Mosque is the second-largest mosque in Central Asia and is adorned with classical Islamic decorations and traditional Kazakh ornaments.

|

I visited the Borovoe Lake in this picture's background on the eastern foothills of Kokshe Mountain with journalists from Azerbaijan and Belgium and a Kazakh civil servant and diplomat. (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

Schuchye Lake at sunset from the Rixos Resort in the Burabay District north of Astana (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

Schuchye Lake at sunset from the Rixos Resort in the Burabay District north of Astana (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

The Expo 2017 Astana on the outskirts of the city -- themed on future energy -- received positive reviews from the New York Times, the Economist and other prominent media outlets for its informative, engaging programs and architectural innovations. The centerpiece is the Nur Alem Kazakh pavilion in the expo site’s center, which is the world’s largest spherical edifice showcasing Kazakhstan’s vision and plans for sustainable energy.

“We have a long winter here that lasts for six months, so there’s a lot of potential for winter sports and ecotourism,” said Lee, mentioning the Burabay lakes north of Astana. Surrounded by pine trees, the lake area is a pristine ecotourism destination and popular weekend getaway, also known as “the Pearl of Kazakhstan.” The lakes and mountains are laden with occult legends that have been orally handed down through generations.

Lee encouraged Koreans and foreign visitors to come to Kazakhstan for hiking, mountaineering and other leisurely activities across the country’s vast, unoccupied territories.

Both of my visits to Kazakhstan -- covering Almaty, Astana and Burabay -- were full of the warmth and hospitality of the local Kazakhs who accompanied me. I asked Lee, a 35-year-old fourth-generation ethnic Korean, what makes the people so friendly and warm-hearted.

|

Kazakh girls pose at the First President's Park in Almaty (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

The Ascension Cathedral in Almaty (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

“When people are struck by a calamity or hardship and in need, they tend to come together and help one another,” Lee explicated, referring to the Kazakh people’s embrace of Korean, Chechen, German and other refugees who desperately knocked on their doors in the last century following persecution and expulsion from their homelands.

Some 100,000 ethnic Koreans, known as “Koryo-saram” or “Koryo-in,” settled in Kazakhstan in the late 1930s after being driven out of Russia’s Far East by Joseph Stalin. They found a new home in Kazakhstan and have made great strides in diverse fields, forming a key pillar of the country’s vibrant multiethnic society of some 130 nationalities.

“I think the culture of hospitality came into fruition particularly at this point in time (in the late 1930s),” Lee surmised. “Kazakhs, despite being poor themselves, came out and made the move to welcome these people who were pushed to the brink of death. I heard countless stories told from my grandparents and great grandparents how they scraped by in the steppes eating small bits of bread and dried yogurt ‘kurt’ offered by Kazakhs.”

Turning to his shy, reticent Kazakh wife, he added, “This was truly extraordinary. Not every nation could do such things or had the will to do so. When I look at my wife, I feel that her ancestors have been really nice to our people. Because of our special history, those descendants that survived and laid down their roots here feel it is their duty to reciprocate somehow. Perhaps that is what creates this unique harmony among various ethnicities in Kazakhstan today.”

|

The Big Almaty Lake outside Almaty (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

Mountains surrounding Almaty from the Koktobe Hill park and zoo (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

Lee, who manages the Facebook group “Expats in Kazakhstan” with 7,000 members, encouraged young entrepreneurs, professionals and job seekers to come and live in Astana. Life in Astana used to be difficult in the 1990s, he said, as the country was remaking itself following its independence from the Soviet Union in December 1991. But Astana today is modern, dynamic and full of cultural, educational and entrepreneurial opportunities -- a “huge leap from the challenging 1990s.”

“When I read expats’ posts on Facebook, I can see they are really enjoying their life in Astana,” the journalist commented. “It’s safe and cheap to live here, people are friendly and, most importantly, there’s always room to grow and improve. We still have a lot of challenges, but what really encourages me is that our government is willing to deal with them and improve its governance, transparency and efficiency. It is a slow progress, but the changes are really happening.”

Pointing to the loud cries of babies and children in the restaurant, as similarly heard elsewhere across Kazakhstan, Lee added, “If you want to invest in your future, this is the place to be, to make that happen. I feel like I belong here. This is my place, my home.”

|

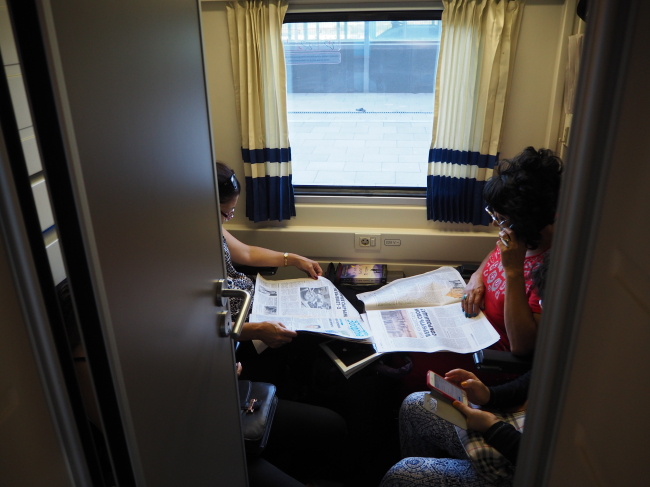

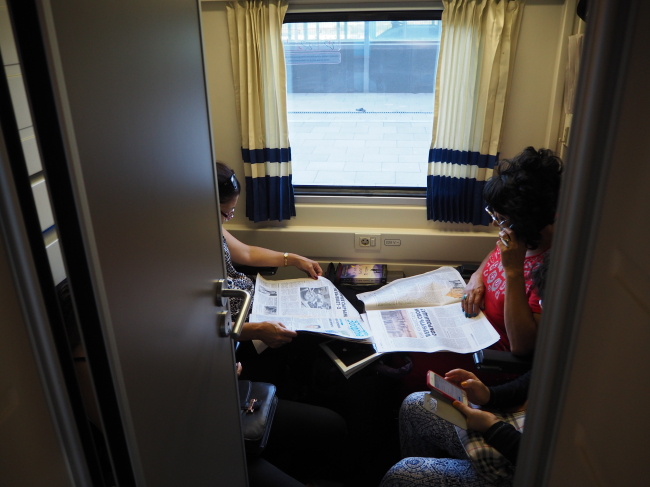

An overnight train from Astana to Almaty on the high-speed Tulpar-Talgo train in late August (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

An overnight train from Astana to Almaty on the high-speed Tulpar-Talgo train in late August (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

During an overnight train from Astana to Almaty on the high-speed Tulpar-Talgo train in late August, I met a German couple from Heilbronn in northern Baden-Wurttemberg.

“When I told my colleagues I was going to travel to Kazakhstan, they looked at me wondrously as if I was flying to the moon. Coming here on a vacation was simply out of their scope of imagination,” said Susanne Sebesteny beside her husband Franz, both of whom work in banking in Germany.

Both were first-time visitors to Kazakhstan and planned to spend 10 days in Astana and Almaty, they said.

“Many Kazakhs couldn’t speak English but they were so open and kind to us. We were able to communicate with a bit of my husband’s Russian knowledge. We felt at home somehow,” Susanne remarked.

|

The view over Almaty from Koktobe at night was mesmerizing to say the least. It's me, the writer of this article. (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

Almaty Central Mosque (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

Similar to ethnic Koreans, Franz, 66, noted that ethnic Germans were scattered across imperial Russia, Ukraine and the Soviet Union from the early 16th century. Their immigration heightened during the reign of Czarina Catherine II, originally from Germany. Most German-Russians came back to Germany in droves following the Soviet Union’s demise in the early 1990s.

“In Russia, they lived as Germans, but when they came to united Germany they were cast aside and discriminated against as Russians,” Susanne, 55, said.

“Discrimination against them has largely dissipated now, but even 10 to 15 years ago they were still seen as outsiders. They had problems in school and at work. It took a long time for them to be fully integrated into the German society,” she said, pointing to Germany’s acceptance of Turkish, Vietnamese, Russian and other migrants and the recent welcoming of refugees from North Africa and the Middle East.

“When I see my colleagues again, I will tell them Kazakhstan was not like the moon, but like a European country busily marching toward a better future. It’s definitely worth visiting here,” she added.

|

A view of rugged mountains from Medeo ice rink outside Almaty (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

Temur (top row, left) poses with his family and relatives at his home on the outskirts of Almaty in late August. I was invited to his home for a feast of Uzbek-Kazakh cuisine. (Joel Lee/The Korea Herald) |

In Almaty, I met Temur, my driver in Astana in June whose main job was as a mechanical engineer at a movie theater. A robustly built 28-year-old, Temur kindly took time to show me in and around Almaty, and later I was even invited to his home for a traditional Uzbek-Kazakh dinner with the company of his family and extended relatives.

Temur’s family, like many in Kazakhstan who came from abroad, previously lived in the small village of Beruniy in the independent republic of Karakalpakstan in Uzbekistan. They settled in Almaty -- the largest municipality in Kazakhstan with 2.5 million people -- in 2003.

“Almaty means ‘the city of apple,’ and is a green city with a long history. It is surrounded by beautiful, tall and craggy mountains,” he said, recommending visits to the Kok-Tobe Hill park and zoo, Medeo ice rink and Shymbulak ski resort, which are connected via cable car, Sharyn Canyon located 200 kilometers east of Almaty, Big Almaty Lake and Lake Kolsai outside the city.

“Kazakh people used to live nomadic lives, with each family huddled together in a yurt,” he said. “As there were not many people around each family except villagers, we warmly welcomed any guests or outsiders. I recommend travelers to Kazakhstan to interact with our friendly people.”

By Joel Lee, Korea Herald Correspondent (

joel@heraldcorp.com)

*** This writer won the fourth international competition "Kazakhstan through the Eyes of Foreign Media" for the Asia, Australia and Oceania part for his article "Ethnic Koreans sow seeds of success in Kazakhstan" published on The Korea Herald in June. As part of the award, staff reporter Joel Lee and other journalists from around the world were invited to tour Kazakhstan in August sponsored by the LOT Polish Airlines, Expo 2017 Astana Railway Company, Kazakhstan Temir Zholy Railway Company, Kazakhstan National Olympic Committee, Ramada Plaza Astana, Rixos Borovoe Hotel and Argymak Transport Company. -- Ed

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)