PANGYO, GYEONGGI PROVINCE -- On a warm Monday morning in July, a rather unusual scene played out at Pangyo Techno Valley in Seongnam, Gyeonggi Province. The South Korean industrial complex is best known as the "Silicon Valley of Asia" -- it is valued for its role in innovation and technology start-ups, focusing on biotech, information technology, among others. Consisting of many high-rise, shimmering buildings that give off futuristic vibes, the complex is certainly not known as the go-to place among Koreans for public rallies and protests. But on July 16, it became a place for a rather rare protest, organized by refugees from Democratic Republic of Congo.

“We don’t want voting machines,” they shouted. “Congolese don’t want voting machines!”

The Congolese-born men and women, some 20 of them, were protesting against Miru Systems Co. Ltd., a South Korean firm located in the industrial complex in Pangyo. While most Koreans are unaware, the firm has been under scrutiny in DR Congo for signing a deal with the country to provide voting machines for their long-awaited elections scheduled Dec. 23.

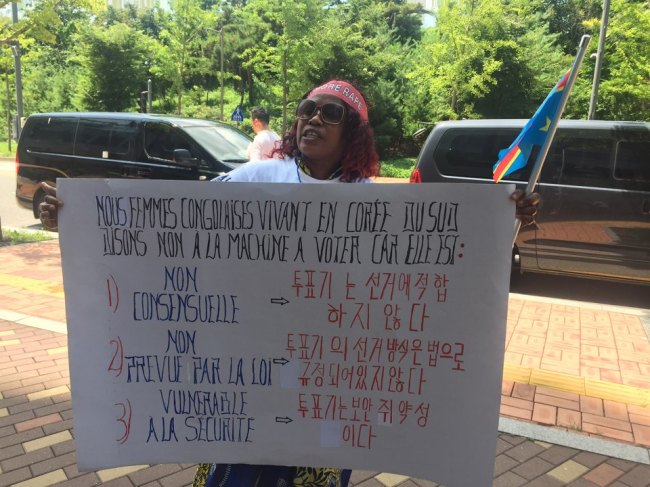

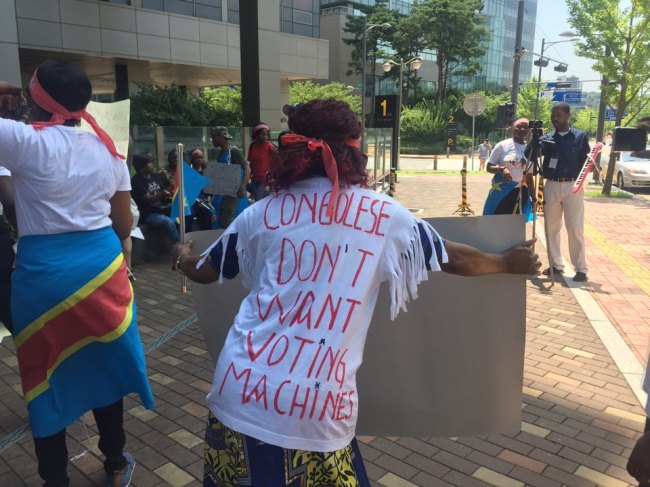

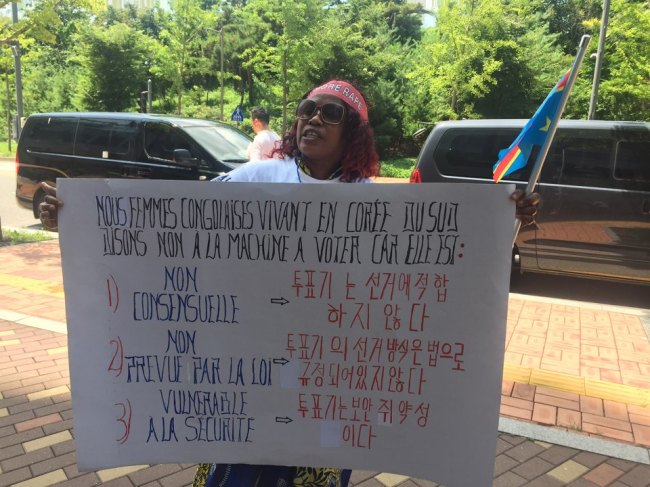

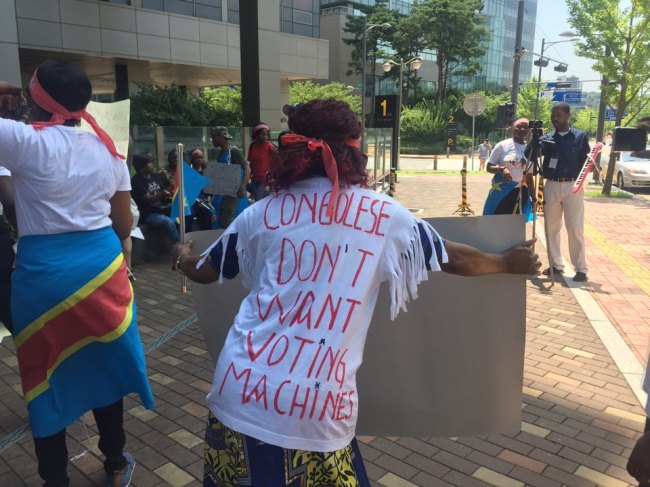

|

Men and women from the Democratic Republic of Congo, many of whom are in Korea as asylum seekers, protest Miru Systems at Pangyo Techno Valley in Pangyo, Gyeonggi Province, on July 16. (Claire Lee/The Korea Herald) |

The upcoming election seeks to end the central African nation’s troubled political crisis that have involved deadly protests. Much of the violence that has plagued the country is linked to its President Joseph Kabila, who has illegally stayed in power beyond his constitutionally mandated two-term limit by deliberately delaying elections. The South Korean firm is supplying some 100,000 machines to DR Congo under the $150 million deal. Meanwhile, nearly two thirds of the 77 million people in DR Congo live on less than $1.90 per day, according to the World Bank Group.

Since the deal was signed between Miru Systems and Congolese authorities earlier this year, many in Congo have been voicing opposition to voting machines. They claim the machines carry a high risk of undermining the reliability of the long-awaited vote, especially as millions of people there are illiterate and do not have access to electricity.

|

Men and women from the Democratic Republic of Congo, many of whom are in Korea as asylum seekers, protest Miru Systems at Pangyo Techno Valley in Pangyo, Gyeonggi Province, on July 16. (Claire Lee/The Korea Herald) |

|

Men and women from the Democratic Republic of Congo, many of whom are in Korea as asylum seekers, protest Miru Systems at Pangyo Techno Valley in Pangyo, Gyeonggi Province, on July 16. (Claire Lee/The Korea Herald) |

Most of the protesters at Pangyo had been forced to flee Congo to avoid possible persecution for their political beliefs or activism. Bwelungu Nombi Henry, an asylum seeker and pastor who arrived in Korea from Congo some 10 years ago, said organizing such a public protest in his home country may have cost him his life. Since 2015, nearly 300 people in Congo have been killed and hundreds more arrested for protesting Kabila’s election delays, according to Human Rights Watch.

Bwelungu said even among the Congolese diaspora, anti-Kabila activists have been poisoned by government agents on missions in the past.

“Congolese people have died before and after every election (in the past),” he told The Korea Herald. “Now with the voting machines more people will die. I have the right to prevent it.”

Firm at center of controversy

Miru Systems, founded in 1999, has been certified as an exceptional small and medium-size enterprise, both by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups and Gyeonggi Provincial Government.

“We have 20 years of know-how in electronic voting system. Digital is a 21st century democratic language. Technology is neutral,” the firm’s English-language website reads.

“A secure electronic election system could further develop democracy. In response to increasing demand for alternatives to manual voting practice, we provide the best electronic voting system that is user-friendly, secure, transparent, and accurate.”

In South Korea, the firm has been supplying optical scan ballot sorting and counting machines -- an electronic vote counting device -- to the National Election Commission of Korea since 2014. The device was used in the country’s presidential election last year.

Overseas, however, the company has been linked to a number of corruption allegations. Miru Systems’ $150 million contract with Congo’s Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI) was partially arranged by A-Web, a Korean nongovernmental organization to connect Korean tech firms to electoral commissions worldwide.

Kim Yong-hi, a former secretary-general of A-Web, is currently under investigation by prosecutors on allegations of embezzlement and bribery, as well as unethical lobbying of high-ranking officials in the electoral commissions of foreign countries to sign deals for electronic voting systems with Miru Systems only. The countries were supposed to select a firm for such a system through an open bidding process.

Notably, prior to joining A-Web, Kim had been serving as secretary-general of South Korea’s National Election Commission. He was appointed in 2014, the same year the NEC selected Miru Systems as the new supplier of the country’s electronic vote counting device for all elections for public offices. Another local firm supplied the device from 2002 to 2014.

According to the office of Rep. Yun Jae-ok of the main opposition Liberty Korea Party, the South Korean government had spent 43 billion won ($38.11 million) in support of A-Web from 2014-2016, the same years Kim served as the head of the NEC.

Crucial elections overseas

According to Miru Systems’ website, the company has supplied its machines to Kyrgyzstan, Russia and El Salvador, as well as Iraq and Congo. Experts point out that the countries that have signed deals with Miru can be considered struggling democracies.

“The question is this. Why are these machines only being used in countries with a bad record of democracy?” Abudlla Hawez, an Iraqi journalist, posed to The Korea Herald.

“I think this makes the machines questionable and not trustworthy given that elections are controversial in these countries, and that people actually want to steal the results. And the machines (by Miru) haven’t been used anywhere where elections are done (in a fair and appropriate manner)."

Miru’s machines have especially caused a controversy in Iraq, for one of the most significant elections in recent years, on top of the upcoming election in Congo.

Last year, the firm signed a $100 million deal with Iraq’s election watchdog to supply its vote counting machines. Miru Systems’ machines were employed at the parliamentary election in May, but electoral complaints and fraud claims arose, with critics arguing that the machines may have been manipulated to favor certain candidates.

The election had been considered to be a crucial one since it was Iraq’s first general election since the country declared victory over the Islamic State (ISIS).

In June, Iraq’s parliament passed a law ordering a nationwide manual recount of the votes.

Hawez said that in Iraq, staff were not fully trained on the use of the machines and the system was introduced in a rush. At the same time, civil societies and the UN warned the country against using the machines, saying they had not been tested in Iraq and therefore carried a risk.

“With this electronic voting system, the number of people who have lost faith in the democratic process in Iraq is in an all-time high,” he said. “This is why the turnout for the election was about 45 percent, an all-time record low.”

As for Congo, the country’s CENI said it would be impossible to stage elections on schedule without the machines supplied by Miru Systems, claiming the country faces logistical challenges in setting up polling stations and counting votes given its lack of infrastructure, including roads.

Still, a number of countries, including the US, and international NGOs have warned Congo against using the machines. The US said deploying “an unfamiliar technology for the first time during a crucial election is an enormous risk.” Human Rights Watch added that using the machines “creates new opportunities for fraud and the way votes are tallied,” and that many Congolese will “need to be shown how to use the machines, preventing them from casting a secret ballot.”

"You can always re-use the machines"

To these concerns, Sim Sang-min, the director of Miru Systems’ business division, said the machines are very easy to use, even for illiterate voters.

“There will be photos of each and every candidate onscreen,” Sim told The Korea Herald. “Once a candidate is chosen onscreen, the machine will allow the voter to print out the ballot paper, check if everything went correctly, and then put the paper in the ballot boxes. It basically operates as a ballot marking device,” Sim said.

“It seems like some critics think the entire voting process will be done electronically, unaware of the fact that the machine also involves using ballot papers.”

As to allegations by two prominent Congolese NGOs that using the machines would cost three times as much as a paper vote and that it would undermine transparency, Sim said the machines would save costs in the long run. “You can always reuse the machines,” he told The Korea Herald.

Asked about Congo’s political situation, Sim said the company does not intend to interfere with Congolese politics.

’There is no law, no justice’

Manumbunu Marie Claire Makelo, one of the Congolese women at the Pangyo demonstration on July 16, was wearing a red headband that read “No more rape,” alongside female colleagues.

“The color red represents blood of the people in Congo,” Makelo said. “So many people have died. So many women have been raped. There is no law, there is no justice in my home country.”

Makelo fled to South Korea some three years ago, feeling it unsafe to live in Congo after her husband, a soldier, was killed by a colleague. To this day, she still doesn’t know why her husband was killed. “Such unexplained deaths are not uncommon in Congo,” she said.

Congo remains one of the most troubled nations in the world. The UN has labeled the country “the rape capital of the world.” In 2011, 48 Congolese women were estimated to have been raped every hour. In June, a report by the UN Human Rights Council revealed boys are being forced to rape their mothers, while women are forced to choose gang rape or death, among other atrocities, in the conflict-ridden Kasai region of Congo.

The Congolese protesters in Korea said by signing a deal with the corrupt Congolese government, Miru Systems is complicit in the ongoing violence plaguing the central African nation.

Although Kabila is not eligible under Congolese law to seek a third term, they said, he has yet to announce whether he will indeed step down, fueling speculation he may attempt to revise the country’s constitution to run again.

In April, the Korean government released a statement on the situation through its embassy in Kinshasa, saying the use of Miru Systems’ machines “had failed to gain support from international agencies.”

The statement added, however, that the Korean government has “no legal right to forcibly discourage a private Korean firm from exporting its products.”

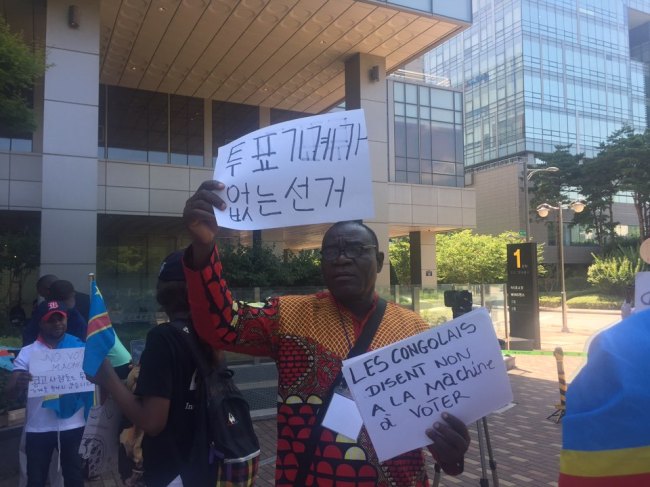

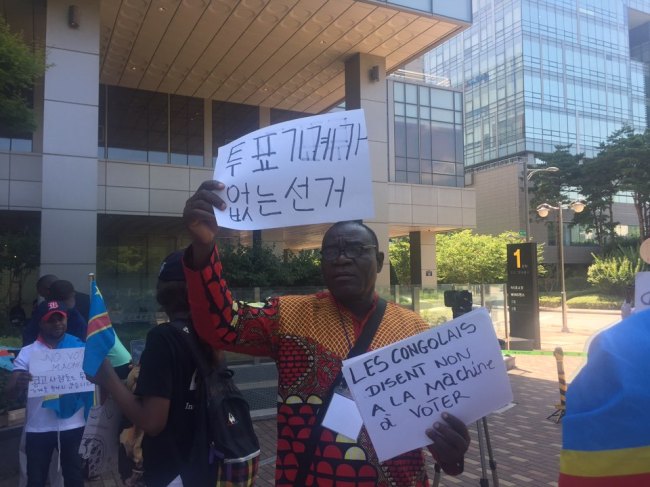

|

A Congolese protester holds a sign that says "Election without Voting Machines," written in the Korean langauge. (Claire Lee/ The Korea Herald) |

|

Men and women from the Democratic Republic of Congo, many of whom are in Korea as asylum seekers, protest Miru Systems at Pangyo Techno Valley in Pangyo, Gyeonggi Province, on July 16. (Claire Lee/The Korea Herald) |

As Miru Systems and the CENI would not cancel their deal, the Congolese refugees in Korea submitted a statement to the company on July 16, requesting the company not supply the machines to their home country. The same statement was also submitted to the National Assembly and the Justice Ministry, as well as the National Election Commission, Bwelungu said.

“We believe the voting machine will be a source of post-election conflict in Congo,” the statement said. “We wish the use of paper ballots that is the fairest way for our country to have election.”

After the demonstration on July 16, Bwelungu said he received a missed call from Congo that he could not identify. On the same day he also got a call from a person whom he identified as a spy. “I could not sleep that night,” he said.

Bwelungu said the group’s activism is also aimed at warning Miru Systems and the Korean government of unexpected consequences. By not canceling the contract with CENI, he said, the company may be putting Koreans living in Congo in danger. “We believe this can raise a conflict between Congolese and Korean residents in Congo,” he said.

Following the submission of their statement, Bwelungu said he and his fellow activists have been invited to meet with the general secretary of the National Election Commission of Korea later this month.

“I feel indebted to those who live in my home country,” Bwelungu told The Korea Herald. “I cannot physically be with them, so this (activism) is the least I can do for them.”

By Claire Lee (

dyc@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)