At a glance, the daughter of the newly appointed Justice Minister Cho Kuk has led a charmed life. Her wealthy, highly educated parents with powerful and respected jobs have given her an elite background and the privileges that come with it.

Cho’s 28-year-old daughter graduated from a prestigious foreign language high school. In her second year in high school, she was improperly listed as a primary author in a paper published in a medical journal. She then gained admission to a prestigious university. During her college years, she received a certificate her mother, a professor at Dongyang University, is suspected of having forged to help her get into a medical school.

|

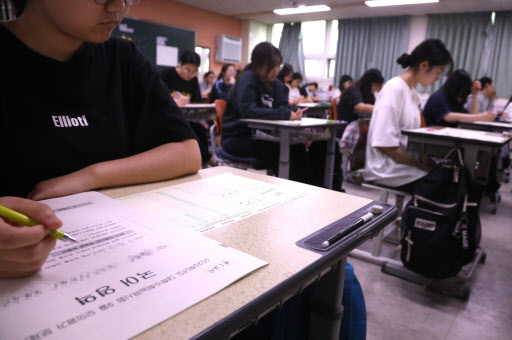

Students at Sangam High School in western Seoul take mock College Scholastic Ability Test on Sept. 4. (Yonhap) |

The advantages Cho’s daughter enjoyed allegedly on the back of Cho’s connections and social status has rekindled a debate in Korea over the fairness of the current college admissions system, leading President Moon Jae-in to order a “comprehensive review” of the system earlier this month.

“It seems weird that Cho’s daughter has all these ‘specifications’ – such as internship experience and being listed as a primary author in a journal – that are difficult for ordinary students to have,” said Ryu Gyeong-seok, who started at a university in Seoul in 2015.

Specifications, usually shortened to spec, is used in Korea to refer to qualifications and other achievements and experiences that can be listed on a resume to increase the chances of, for example, landing a job or a place at university.

“Extracurricular activities that we can record on our school report card seem to be decided by parents’ occupation, financial capacity and connections,” said Ryu, who was admitted through an admissions track called “susi” that takes into consideration a number of other factors in addition to school grades in offering admissions. “Jeongsi,” the other admissions track, admits students based on college aptitude test scores. Cho’s daughter was also admitted to the university under the susi track.

While susi was designed to widen the path to college, it has been open to abuse, as demonstrated by the case of Cho Kuk’s daughter.

To make the system fairer, the government seeks to close the loopholes in the college admissions system.

Critics, however, say the only way to objectively measure an applicant’s qualifications is to go back to expanding the traditional admissions track – evaluating students based on their college aptitude test scores.

Suneung vs. susi

Following a nationwide debate last year, the government said that up to 30 percent of total university applicants will be accepted through the College Scholastic Ability Test – called suneung – and the rest through the non-standardized track, starting in the academic year 2020.

In Korea, whose Confucian tradition places a premium on education, a college degree has widely been considered to guarantee upward social mobility. This led to notoriously fierce competition for a place at top universities, as one’s future – from employment to marriage prospects –was deemed tied to one’s degree.

|

A student fills in a College Scholastic Ability Test application form at an education support office in western Seoul on Aug. 22. (Yonhap) |

Nearly 70 percent of high school graduates in Korea aged between 25 and 34 were enrolled in tertiary education institute as of 2018, ranking first place for the 11th consecutive year among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development member states.

After liberation from Japan in 1945, the government only set the date and subjects of the college entrance exam, giving much leeway to universities in selecting their freshmen class. This, however, gave rise to admissions irregularities and fanned costly private tutoring.

The nationwide annual college-entrance exam came into being in 1982, but which was criticized for promoting rote-learning and forcing students into cram schools.

The government then adopted suneung system in 1994 designed to measure students’ ability more comprehensively – taking into account students’ school records as well. But this did not lessen the intense pressure on students and reliance on private education.

How much suneung should be weighed in college admissions has been a key source of debate.

For the past decade, Korea has moved away from suneung and expanded the weight for things other than standardized tests in college admissions, in hopes that students would be able to spend more time finding their own interests and talents rather than preparing for mostly multiple-choice tests.

Public opinion is largely divided into two -- those who favor the standardized exam testing students on subjects including English, mathematics and Korean history, and those in favor of the non-standardized path of screening university applicants.

“Cho’s daughter is a typical case of privilege,” said a university student, 24, who wanted to be identified only by his surname Jeong. “The early admissions track has much room for the rich and the powerful to employ expedient options. I think suneung is the fairest option.”

According to a survey of 501 adults by local pollster Realmeter released on Sept. 5, 63.2 percent of the respondents said he standardized track of college admissions is more “desirable.”

“It is impossible to make susi system fair and transparent because it is based on qualitative and subjective measurements,” said Lee Jong-bae, who heads a civic group campaigning for fair society.

“For suneung, students themselves take the exams, though they could get help from private education in preparing for the exam,” he said. “For susi, it is difficult for students to be convinced about the result because it is unclear how the students are evaluated, by what standards.”

The young were more likely to support suneung, with 72.5 percent of those aged between 19 and 29 supporting the standardized track.

Lee Jae-won, 24, who believed one’s yearslong academic efforts at middle and high schools could pay off, also felt “deprived” in the wake of the scandal.

“But I oppose the unified way of evaluating students through suneung. That would be a step backward,” said Lee, who attends a prestigious university in Seoul.

“I think the system should be fixed so that external forces other than students’ academic ability are kept out of the admissions process.”

‘Hierarchy among schools, jobs should be curbed’

In response to Moon’s call for a review of the college admissions system, the Education Ministry has launched discussions on fixing the system. Any changes in the system will be in place for students applying for colleges starting in 2024.

Moon’s order, however, has also sparked concerns that it would result in an unsustainable quick fix.

|

Students march at Korea University campus in Seoul on Aug. 23 in protest against Cho Kuk, whose daughter faces allegations of university admission irregularities. (Yonhap) |

Jo Sung-chul, a spokesperson for Korean Federation of Teachers’ Associations, said that the admissions system should not be “swayed” by a president’s words.

“If there are problems, they should be fixed gradually and in the long term, given that even small changes in the college admissions system have great impact on the whole society,” he said. “Such changes to ensure fairness could only result in the elite class (who are fast to adapt to the changes.)

University student Jeong asked for “consistency” in education policies.

“For a student, it is unfair and I am angry that the college admissions system frequently changes. It is too confusing,” he said. “At the very least, education policies should have consistency, and not be used politically.”

Jun Kyong-won, director of ChamGyoyook Research Institute, said that removing some sections – such as a list of awards, certificates or personal statements – in the non-standardized admissions scheme could help enhance fairness.

“Also, the universities must meet their public accountability by making public the information on the applicants they accepted based on types of high schools they graduated and cities they came from, for example,” he said. “That way, they would consider the public good more when selecting applicants.”

More fundamentally, a fair university entrance system could start with the removal of hierarchy in high schools and fixing corporate recruitment systems, which usually favor graduates from prestigious universities, he said.

In Korea, there are autonomous and special-purpose high schools that are considered elite schools likely to send more students to top-tier universities. They have been criticized for contributing to the disparity in academic achievement among students.

“In the long term, every student should be evaluated on an absolute grading system, so that they can be relieved from academic pressure and stress,” Jun said.

By Ock Hyun-ju (

laeticia.ock@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)