The inter-Korean military agreement that was hailed as a “nonaggression pact” when it was signed just a year ago has become a “merely nominal” agreement as its first anniversary approaches Thursday.

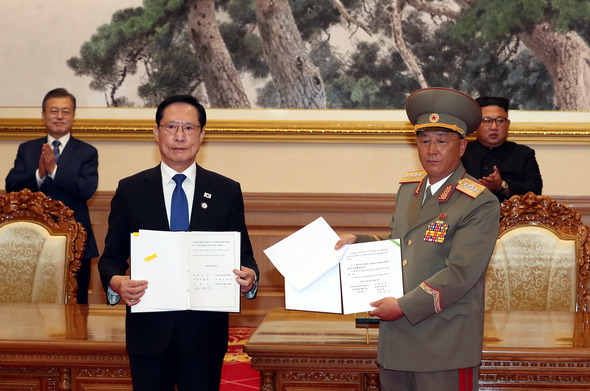

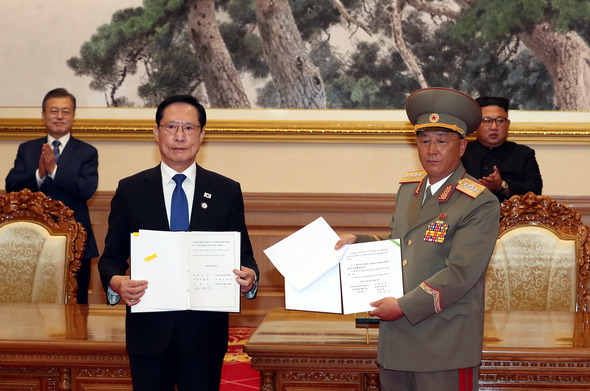

The defense chiefs of the two Koreas signed the Comprehensive Military Agreement on Sept. 19, 2018, in Pyongyang on the sidelines of the third summit between South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

|

South Korean Defense Minister Song Young-moo and North Korean Minister of the People’s Armed Forces No Kwang-chol stand before reporters after signing the Comprehensive Military Agreement on Sept. 19, 2018. (Yonhap) |

It was not the first bilateral military agreement between the two sides. But the CMA, which created buffer zones around the borders to prevent skirmishes, was hailed by the administration and the ruling party as a breakthrough. National security director Chung Eui-yong called it a virtual nonaggression pact that would eliminate military clashes on the Korean Peninsula.

Although there have been no military clashes in the past year, the implementation of the agreement lost steam after the second summit between US President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un ended without a deal earlier this year.

In fact, Pyongyang has used the bilateral pact to reproach Seoul, while it remains unresponsive to the South’s efforts to see to its joint implementation. Pyongyang has also launched short-range projectiles into the East Sea on more than 10 occasions this year, its weapons capable of reaching all parts of South Korea.

Experts and government officials here say it is highly unlikely that the communist regime will move to implement the military pact of its own volition.

“North Korea has prioritized the denuclearization negotiations (with the US). Since the North gained a direct channel for dialogue with the US, it appears largely uninterested in implementing the military agreement with the South,” Cho Nam-hoon, a senior research fellow at the Korea Institute for Defense Analyses, said Monday at the National Assembly at a seminar hosted by Rep. Ahn Gyu-baek, head of the National Assembly Defense Committee.

Sluggish progress

The scope of the military pact that North Korea agreed to was broader than many here had expected, and in the initial months after it was signed the North appeared eager to fulfill its pledges.

The two sides created “buffer zones” around the border areas on land, air and sea. All live-fire artillery drills and field training exercises at various levels have been banned within 5 kilometers of the Military Demarcation Line. Specific areas were set around the de facto maritime borders, banning similar military drills, and “No Fly Zones” were designated to prevent aircraft from flying too close to the border.

|

South Korean soldiers are seen at Arrowhead Ridge as they build a tactical road across the Military Demarcation Line inside the Demilitarized Zone in Cheorwon, Gangwon Province, South Korea, on Nov. 22, 2018. (Yonhap) |

The two sides also removed a number of guard posts close to the border and completely disarmed the Joint Security Area in the border village of Panmunjom, where troops from the two Koreas face each other.

The North also followed through with the accord to remove land mines that had been left buried for decades, to facilitate the joint operation to recover war remains in the DMZ.

Pyongyang’s disinterest, however, became evident at the turn of the year, as its denuclearization talks with Washington became bogged down.

Little progress has been made toward establishing the Inter-Korean Joint Military Committee that was to oversee the implementation of the military pact. The committee was to be the two Koreas’ channel for “consultations on matters including large-scale military exercises and military buildup aimed at each other.”

According to the South’s military officials, while the North openly denounces the South’s joint military exercises with the US, it has not responded to Seoul’s call to form the committee.

On April 1, the agreed date for the joint recovery project inside the DMZ, South Korea kicked off the excavation work on the southern side of the Military Demarcation Line without the North.

The envisioned plan to allow free movement inside the JSA has also been put on hold.

Despite the North’s apparent lack of commitment to the inter-Korean military pact, the South Korean government has largely chosen to keep quiet.

Listing some of the achievements made regarding the CMA, Defense Minister Jeong Kyeong-doo acknowledged that it would take time and effort to implement.

“It is (almost) the anniversary of the CMA, but the situation is tough. It is hard to overcome the competition and conflict that have been ongoing for the past 70 years,” Jeong said at Monday’s seminar.

When Pyongyang fired short-range projectiles into the East Sea for the 10th time this year on Sept. 10, claiming it was part of a weapons testing and development program like those that all countries pursue, Seoul refrained from saying it violated the CMA.

“The Sept. 19 military accord remains valid. There has not been a single clash between the South and the North around the border areas,” Vice Defense Minister Park Jae-min said Sept. 5 at a plenary session of the Seoul Defense Dialogue.

|

North Korean Lt. Gen. An Ik San (second right) shakes hands with his South Korean counterpart Maj. Gen. Kim Do-gyun during a meeting inside the Peace House at the border village of Panmunjom, South Korea, on July 31, 2018. (AP-Yonhap) |

Prepare for Plan B

For now, North Korea appears to lack interest in making further efforts to implement the inter-Korean accord. At the same time, it claims South Korea is violating the military pact, citing the recent joint South Korea-US military exercises and the deployment of F-35A stealth fighter jets.

“North Korea is misusing the CMA as a tool to denounce South Korea. While the implementation of the bilateral accord is sluggish because of its lack of commitment, the North puts the blame on the South,” Moon Sung-mook, a senior researcher at the Korea Research Institute for National Strategy in Seoul, told The Korea Herald.

“The government maintains that the Sept. 19 military agreement has played a crucial role in preventing military clashes with the North. But there would have been no such clashes anyway, if the two sides had just stuck to the existing Armistice Agreement,” Moon said, referring to the pact signed in 1953 ending the Korean War, which requires both sides to “ensure complete cessation of hostilities and of all acts of armed force in Korea until a final peaceful settlement is achieved.”

North Korea has often violated the Armistice Agreement, Moon said, recalling the naval battles near the border island of Yeonpyeongdo in 1999 and 2002.

Moon, formerly a colonel who participated in working-level military talks in the past, also said the Seoul government should raise a stronger voice against North Korea’s military actions, which may threaten the security of South Korea.

Conservatives who oppose the liberal Moon Jae-in administration’s approach to the North argue that the CMA should be scrapped.

Yet experts believe that the CMA does have merits. For example, it has set the basic rules for arms control on the Korean Peninsula, according to Cho Sung-ryul, a senior research fellow at the Institute for National Security Strategy.

“Past instances show that the smallest military clash between the South and North can lead to a collapse of any confidence-building efforts that had been made previously. So the conventional weapons control (agreed to in the CMA) will contribute to the denuclearization efforts,” Cho told The Korea Herald.

In the meantime, Seoul should maintain a strong defense posture, enough to defend itself against Pyongyang’s conventional weapons, Hong Hyun-ik, a chief researcher at the Sejong Institute, said.

By Jo He-rim (

herim@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] For Korean automakers, Chinese EVs may loom larger than Trump’s tariffs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/14/20241114050537_0.jpg)

![[Graphic News] Tainan predicted top destination for South Koreans in 2025](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/13/20241113050807_0.gif)

![[Herald Review] Cho Seung-woo takes 'Hamlet' crown](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/14/20241114050593_0.jpg)