|

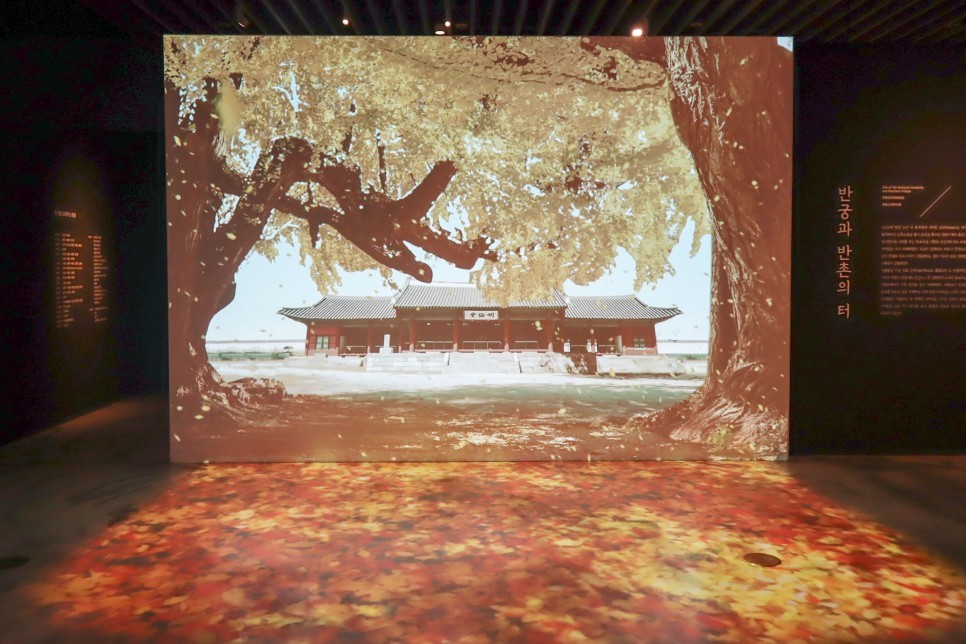

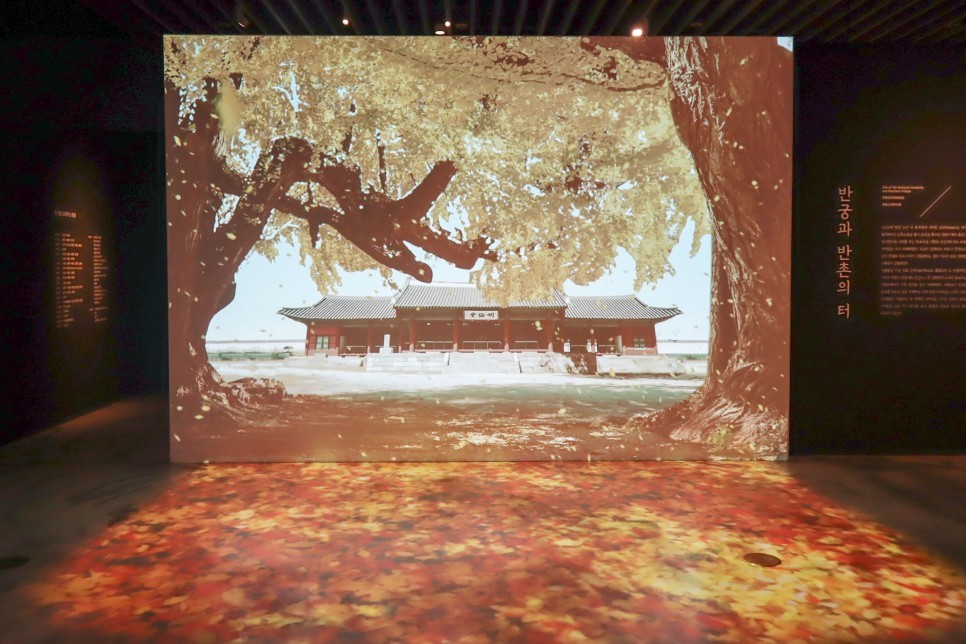

A screen at the start of the exhibition “Sungkyunkwan National Academy and Its Surrounding Village, Banchon” displays Sungkyunkwan’s Myeongnyundang Lecture Hall (Seoul Museum of History) |

“Sungkyunkwan National Academy and Its Surrounding Village, Banchon,” an exhibition running at the Seoul Museum of History, shows Koreans’ obsession with education, which dates back to the Joseon period (1392 to 1910).

The first part of the exhibition showcases the lives of elite students of Sungkyunkwan National Academy, which served as both as a center of higher education and a symbol of Neo-Confucian culture. The academy trained around 200 top students from around the country, who studied for at least 300 days to pass the state exam and become government officials.

“Our exhibition aims to show unique aspects of Seoul. It tells stories about the students and it is also an opportunity to peek into the lives of state-owned slaves called Banin,” In Ji-min, the show’s curator, told The Korea Herald.

The slaves of Sungkyunkwan lived in Banchon, a village surrounding the national academy. The academy and the village were divided by a stream called Bansu.

Visitors can see that Banin are distinct from other state-owned slaves of Hanyang, which is now Seoul. They were originally from Kaesong -- the capital of the Goryeo Kingdom, which preceded the Joseon Kingdom -- and were often described as people with a strong sense of righteousness who were not afraid to express themselves. Moreover, despite their status as slaves, the Banin took great pride in assisting students and serving the national academy.

The Banin originally only served students of the national academy, but in the latter part of the Joseon era, their role expanded.

For instance, in the mid-17th century, some Banin were granted the exclusive right to operate butcher shops, allowing them to earn money like merchants. In return, they were obligated to pay taxes to the government and also donate money to Sungkyunkwan.

Some Banin also became innkeepers, hosting civil service exam takers from outside the capital. Banin would provide services for the students such as serving food and doing laundry. The relationship between the exam takers and the hosts was tight, and those who passed the exam would return to the inn and reward the slaves with money.

Banin also provided a space for entertainment for Sungkyunkwan students. In Banchon, the students could play games like go, which were strictly forbidden at the academy.

Since students were not allowed to study religions other than Confucianism, some students gathered in Banchon and studied Roman Catholic texts together.

To make the exhibition more entertaining, the museum uses digital screens. For example, three giant digital screens near the end of the exhibition display a short video about the slaves of Banchon.

“The short film ‘Story of Banchon’ was created by the museum to more effectively show the relationship between Banin and exam takers,” In said. “It was also created to appeal to young visitors.”

The exhibition, which opened Nov. 8 last year, will run through March 1. Opening hours are from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. on weekdays, except for Mondays, and 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. on Saturdays, Sundays and holidays. For more information about the exhibition, visit the museum’s website at museum.seoul.go.kr.

By Song Seung-hyun (

ssh@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)