South Korea -- with its high-speed internet infrastructure and people quick to learn new technologies -- may seem like it is better prepared than any other country to herald in a new era of e-learning.

But, when the government announced that schools, ready or not, have to go online due to the coronavirus pandemic, many students and teachers were clueless what to expect.

“I just don’t have an idea how online classes will go,” Park Kyung-ah, a mother of two, said. “I don’t think my 9-year-old child can concentrate without me being at home to check on him,” she added.

It has already been a month since her children, aged 9 and 6, last saw their teachers, as all schools, kindergartens and daycare centers in the country were closed due to the spread of the novel coronavirus.

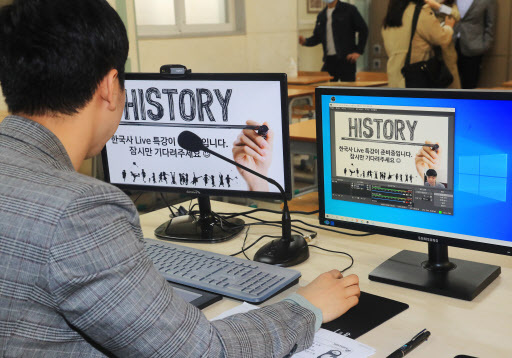

South Korea decided Tuesday to further extend the closure and shift to online classes in the biggest distance-learning experiment in the country’s history.

Online learning will start in stages, starting April 9 for high school students first. The first to third graders of elementary schools will start on April 20.

It is too early to send students back to classrooms, with daily new infections still fluctuating around 100 cases, with a growing number of imported cases from abroad and sporadic clusters of local transmissions, the government said.

Parents and teachers The Korea Herald interviewed all agreed that virus risks are too high for schools to reopen.

Yet, online classes will be fraught with challenges, they said.

“Preparing lunches would be a challenge,” said Park, who has relied on schools to feed and keeping her children safe, like many other households with both parents working. “I think I would have to either take more leave or quit my job.”

Parents can send children to “child care classrooms” set up at designated schools, where a caretaker looks after them during the day, but the service is not widely used amid safety concerns.

According to a survey by the Ministry of Labor and Employment on 500 workers, 42.6 percent of the respondents said they had asked their parents or relatives to look after their children and only 14.6 percent sent their children to “child care classrooms” during the closure of the schools.

And some homes lack the technological infrastructure needed for online learning.

“For a parent like me who has two middle school children, they could go online taking classes without parents,” said Park Ji-young, working mother whose two children attend middle school.

“But I have two children and only one laptop. If they take classes online at the same time, then I will probably have to rent one. I don’t know whether schools are prepared for it,” she said.

To narrow the study gap arising from accessibility to technology, the government said it would provide students in low-income families with smart devices and internet connections starting this week.

According to the Ministry of Education’s survey on 67 percent of schools nationwide, 170,000 students from low-income families did not have smart devices.

The ministry said Wednesday it will lend a total of 316,000 smart devices to the low-income families -- an estimated 230,000 devices ready for use at schools nationwide, 50,000 devices owned by the ministry and 36,000 donated by Samsung Electronics and LG Electronics. The country’s mobile carriers agreed not to charge those using educational websites and digital textbooks.

Parents also worried about children missing out on interacting with their peers in classrooms and learning social skills.

“At this point, it is right to begin a semester online without sending children to school. But my children say they really want to go back to school,” said Lee Geun-young, mother of fifth-grader in elementary school and third-grader in middle school.

“They only liked staying home without going to school at the beginning,” she said.

Confusion is growing among teachers on the front line.

“We haven’t been preparing and haven’t been informed what online learning will be like,” said Park Su-ah, who lives in Goyang, Gyeonggi Province, an elementary school teacher for sixth graders.

“We don’t know whether we should do it in real-time or whether students will just download content ... and I don’t know whether students can concentrate. It is confusing,” she said.

“I am mostly worried that situations faced by families, teachers and schools all vary,” she said. “There are also families without smart devices and teachers who are not familiar at all with the internet or smart education.”

Another teacher based in Daegu, who only gave his surname Noh and teaches first graders in high school, said he is concerned that he has to greet his students starting their high school life online.

“I have not formed any rapport with them as we begin the semester online,” he said. “Students don’t know me and I don’t know them. … I am wondering whether I can offer them classes and assignments customized for their academic level.

The number of students at elementary, middle and high schools is estimated at 5.4 million as of last year -- number of teachers is 497,000.

(

laeticia.ock@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)