|

Nam June Paik Art Center in Yongin City, Gyeonggi Province (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

The following is part of a series that explores museums dedicated to Korea’s well-known contemporary artists that bear their name. --Ed.

There is a street named Paiknamjune-ro, in Yongin City, Gyeonggi Province, where Nam June Paik Art Center, the only art center in the world dedicated to the artist who founded the video art genre, stands majestically.

With its facade of reflective printed-glass, the building looks like a grand piano, an instrument Paik loved as a music major in college. The building was co-designed by two German architects, Kirsten Schemel and Marina Stankovic.

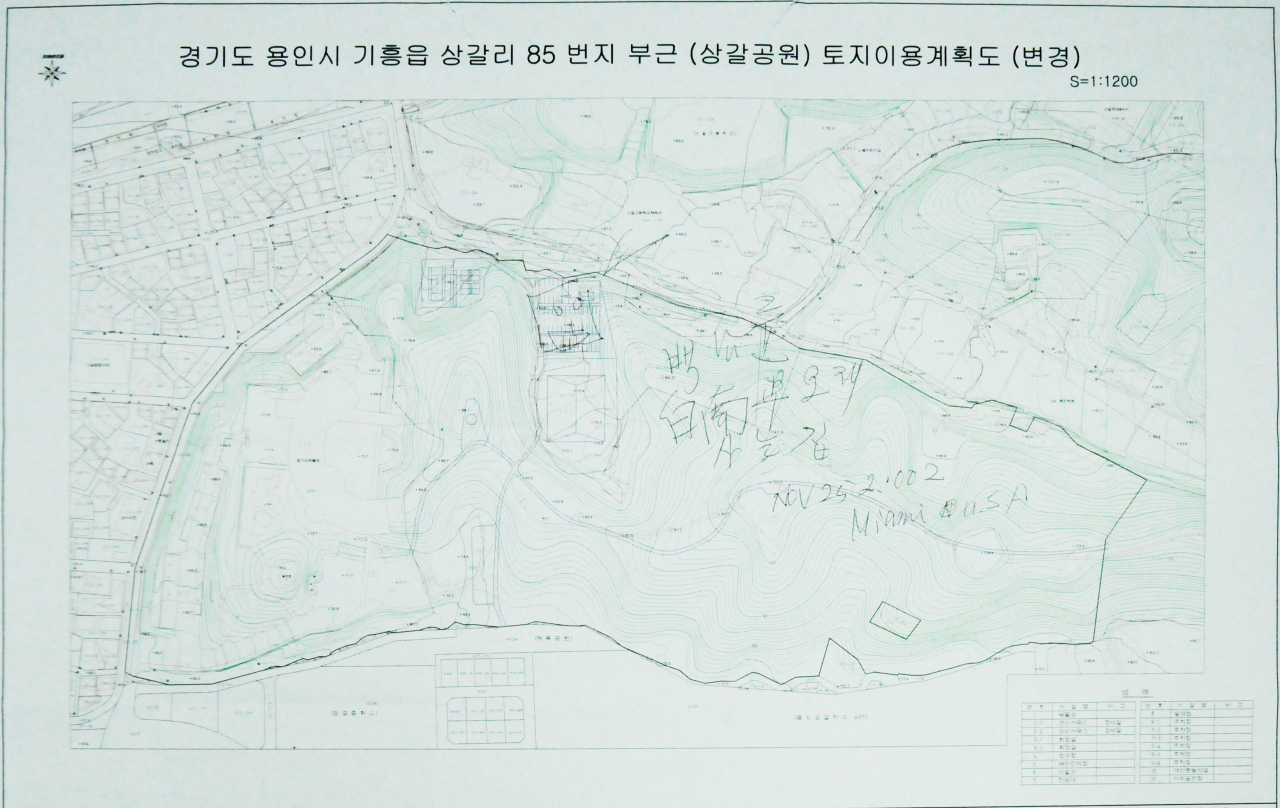

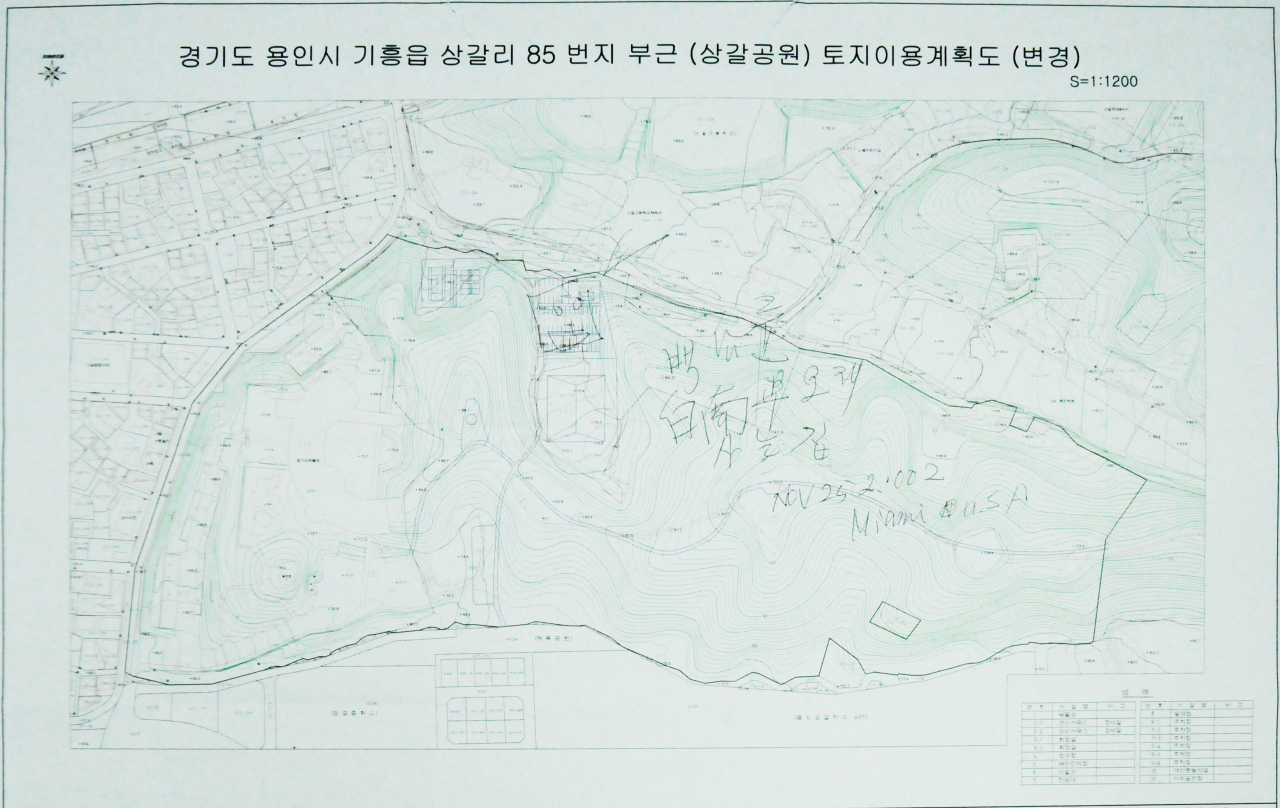

“The house where the spirit of Nam June Paik lives on,” the artist wrote on the blue print of the art center in 2002, the year it was decided that it would be built in the city.

“Not many people know that the art center was built in discussion with Paik while he was alive,” Kim Seong-eun, director of Nam June Paik Art Center told The Korea Herald on May 19. “In 1999, then Gyeonggi Province Gov. Lim Chang-yul met Paik in New York, which led to the establishment of the art center a few years later.”

The Korean-born artist, however, died of a stroke in January 2006 in Florida, US, at the age of 73. The ground breaking for the center would take place later that year, before its opening in October 2008. After his death, the art center faced difficulties with copyright issues involving Paik’s collection, but “those who were in charge of running the art center solved the problem wisely,” Kim said.

Building a video art center appears to have been Paik’s long-time wish well before discussions began on the Nam June Paik Art Center, according to director Kim.

|

Nam June Paik’s signature onsite plan of Nam June Paik Art Center (courtesy of Nam June Paik Art Center) |

In an essay Paik wrote after John Cage, his beloved avant-garde composer, died in 1992, Paik includes his will in a witty way: “I will write down my (will) so that I cannot retract it later … financially 40 percent (of my money) should be spent for a modest video computer arts museum. It should open in 2010 (I may or may not be alive) and close in 2032 (I will be 100 years old).”

The will included in the essay, however, is not official, and closing of the video computer arts museum he mentioned does not mean the closing of Nam June Paik Art Center because it was written before the art center was founded, Kim explained.

“Many of Paik’s writings and drawings convey his sense of humor, which is often reflected in his artworks as well,” Kim said.

The annual budget of the art center, which hosts a yearlong exhibition of the artist’s works and six other special exhibitions related to Paik’s philosophy, including “Nam June Paik Art Center Prize Winner’s exhibition,” comes from Gyeonggi Province and amounts to around 3 billion won.

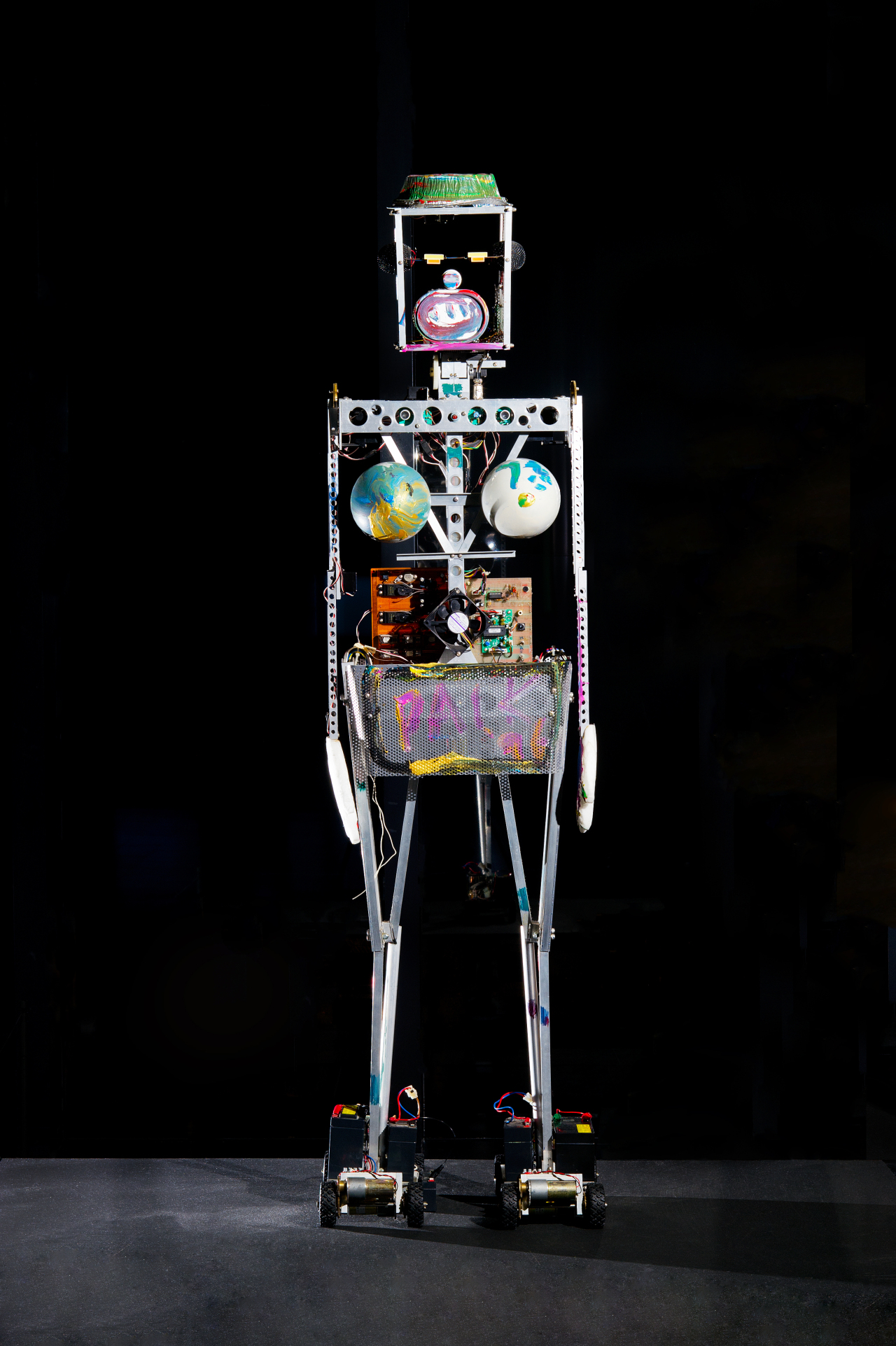

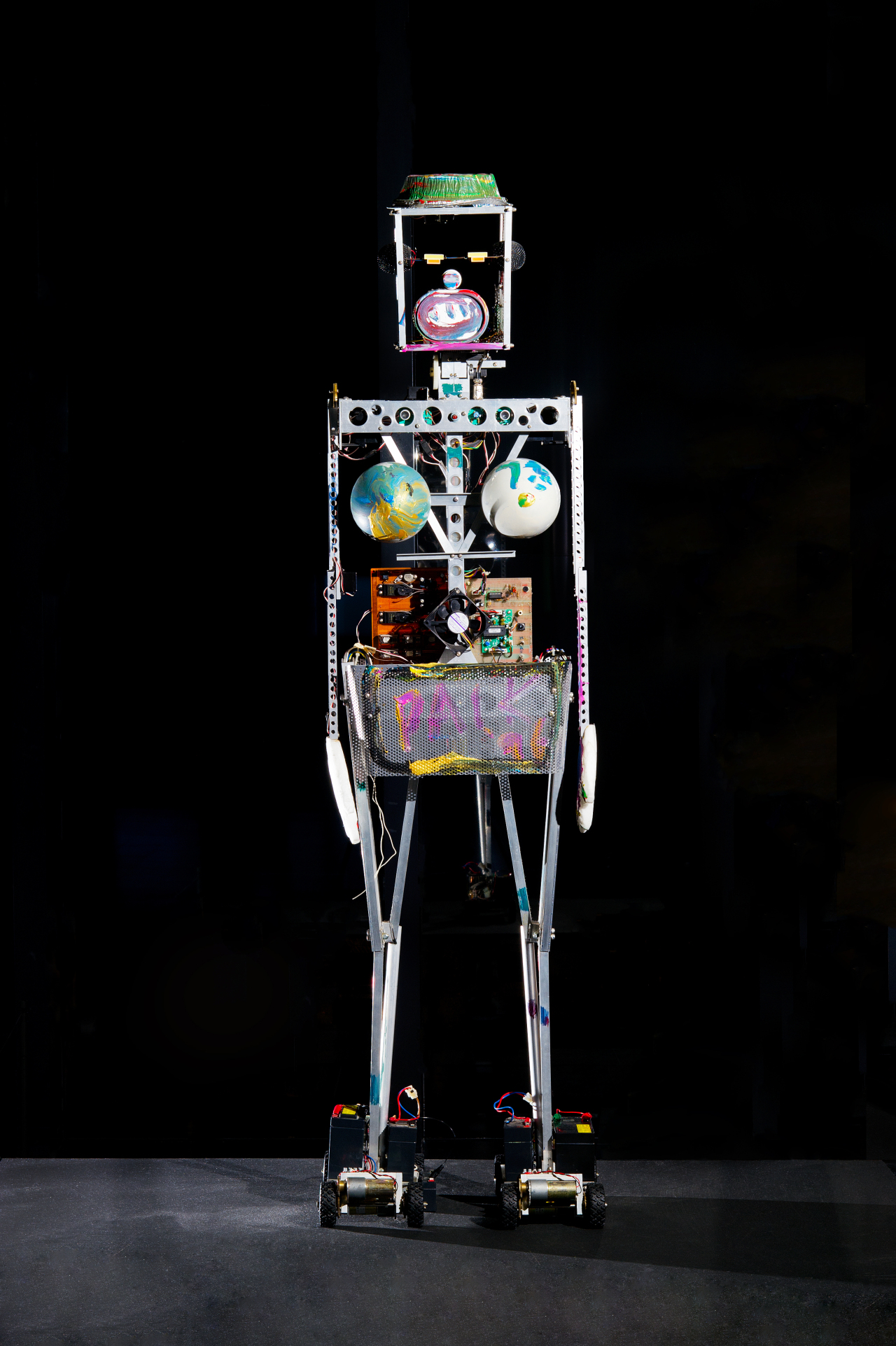

Born in Korea in 1932, when Korea was under Japanese colonial rule, Paik studied in Japan and Germany where he fell into avant-garde art, influenced by American composer John Cage. Paik also became involved with the Fluxus art movement, an experimental movement that aimed to break the mold of traditional art. He was fascinated by new technologies and the TV set, which was a relatively rare electronic appliance in the early 1960s.

|

Paik Nam-june’s “Robot K-456” at Nam June Paik Art Center (Courtesy of Nam June Paik Art Center ⓒ Nam June Paik Estate) |

Paik studied electrical engineering on his own for years in order to merge TV sets into his art, proving how art and technology can coexist in harmony at a time when people were unfamiliar with the convergence of the two different fields. In 1963, Paik presented the world’s first video art exhibition, “Exposition of Music -- Electronic Television” in Germany.

While some criticized the new medium, or were wary of the negative impacts of the new technology, Paik emphasized the positive functions, sending the message that technology, nature and humankind can go together.

The art center is home to some 119 artworks by Paik, including the artist masterpieces “TV Garden,” “TV Fish,” and “The Rehabilitation of Genghis-Khan.” It also houses 2,285 video footage by Paik stored in analogue media such as VHS tapes that Paik used.

After the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the center for near three months, it recently reopened with the exhibition, “Nam June Paik TV Wave,” that displays his experiments with and exploration of television, showcasing his works from the 1960s to the 1980s.

|

Installation view of “Nam June Paik TV Wave” at Nam June Paik Art Center (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

Included in the exhibition is “Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer,” that was created in collaboration with Japanese engineer Shuya Abe in 1969. Paik wanted to show how TV could be manipulated as a piano by anyone. The synthesizer was later used in Video Commune, a live broadcast on WGBH in Boston in 1970.

Nam June Paik Art Center had worked with Abe in 2011 to recover the functionality of the synthesizer.

As the world’s sole art center dedicated to Paik, director Kim said it has a responsibility to promote discussions on how to conserve Paik’s artworks whose now outdated monitors are gradually becoming obsolete. A total of 296 monitors that form parts of Paik’s works at the art center are cathode-ray tube monitors.

|

Kim Seong-eun, Director at Nam June Paik Art Center, poses at the art center. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

“We have three back-up monitors for each CRT monitor, which means the artworks with CRT screens have at least a 10-year life span,” director Kim said. “For now, we are trying to secure as many CRT monitors as possible, but we need a long-term plan on how to conserve his artworks because we can’t stick to CRT monitors forever when they are becoming rare due to the low demand.

“The problem with today’s monitors with new technology is that they are too flat to embody an aesthetic sense. But many years from now and as technology advances, I expect monitors with curved screens will come out. That way we can keep the Paik’s original works, replacing the CRT monitors with monitors with new technology. Until then, we are acquiring CRT monitors in diverse ways,” she said.

Last year, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea decided to keep Paik’s “The More the Better,” the largest video art at MMCA Gwacheon, in its original form by repairing broken CRT monitors, instead of replacing them with those with new technology such as LCD and OLED monitors. The three-year restoration project kicks off this year after more than two years of discussion.

“I think having a thorough discussion on restoration is important, because we cannot find an answer to how to conserve Paik’s artworks in a single discussion. It is an important matter,” Kim said.

By Park Yuna (

yunapark@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] How Gopizza got big in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/20/20241120050057_0.jpg)

![[KH Explains] Dissecting Hyundai Motor's lobbying in US](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/20/20241120050034_0.jpg)