|

Kim Whan-ki archive, including the artist’s painting supplies and a guitar he played, are on display at Whanki Museum. (Park Hyun-koo/ The Korea Herald) |

The following is part of a series that explores museums dedicated to Korea’s well-known contemporary artists that bear their name. --Ed.

If you are interested in Korea’s modern fine art, you may be familiar with Kim Whan-ki’s masterpiece “05-IV-71 #200 (Universe),” a piece that recorded the highest-ever price for a Korean artwork sold at an auction by fetching 13.2 billion won ($10.8 million) at a Hong Kong auction last year.

Born in 1913, Kim was a pioneer of Korean abstract paintings. Paintings that fill large canvases -- “05-IV-71 #200 (Universe)” measured 2.5 meters-by-2.5 meters -- with dots and lines, have become his signature works.

Kim experimented with this way of painting in the late 1960s while staying in New York and developed it through 1974 when he passed away.

“(…) the lines I paint; would they have gotten closer to the sky? The dots that I paint, have I painted as any as the stars twinkling in the sky? When I close my eyes, the mountains and rivers of my homeland appear brighter than the rainbow … ,” Kim wrote in his diary on Jan. 27, 1970.

Standing in front of a large canvas of dots, one is overwhelmed by the force the painting gives off, conveying the sanctity of nature and Kim’s longing for his hometown, a small rural town in South Jeolla Province.

|

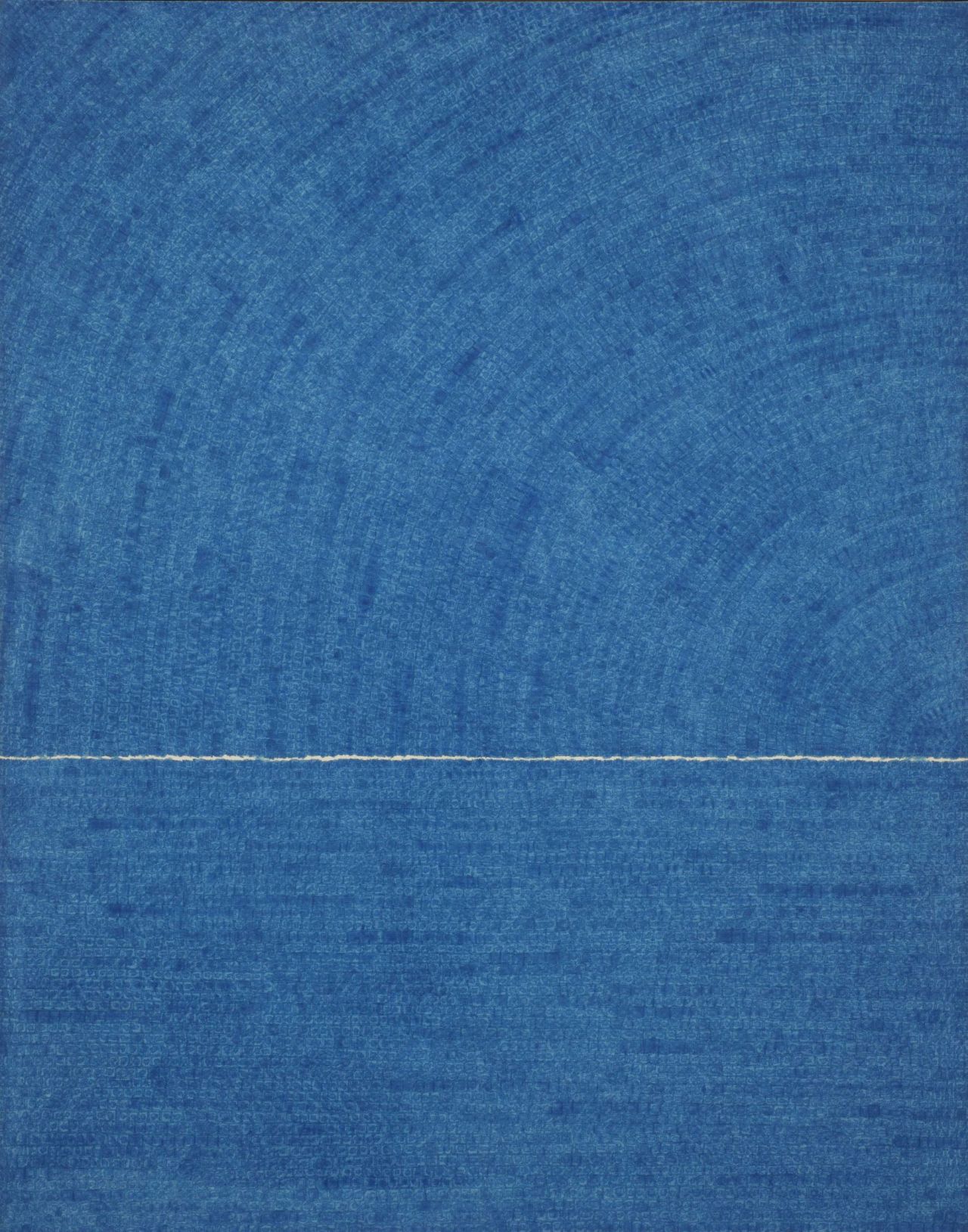

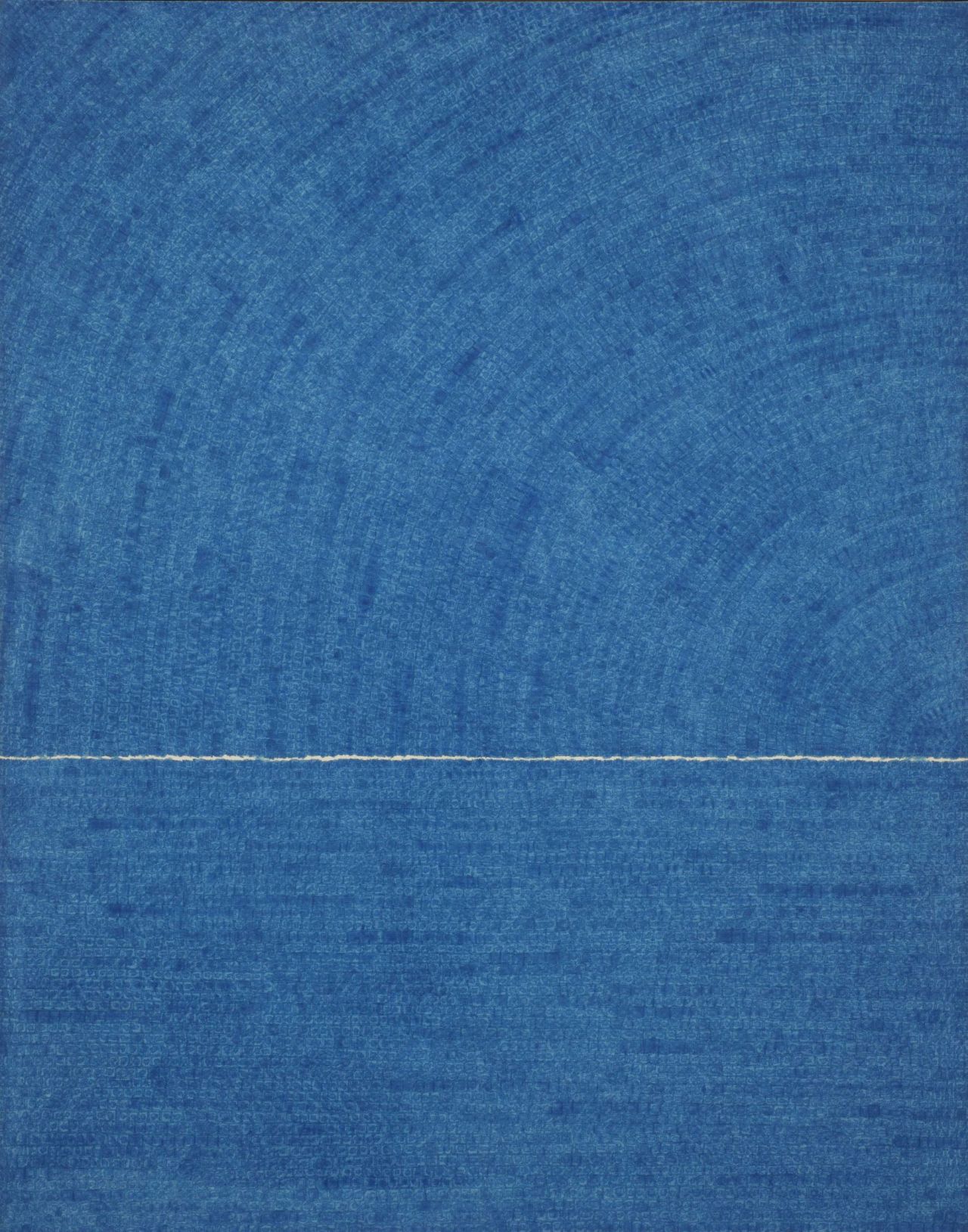

“Air and Sound (I) 2-X-73 #321” by Kim Whan-ki (Whanki Foundation and Whanki Museum) |

Kim’s dotted paintings led the way to “dansaekhwa,” which is also known as Korea’s monochrome paintings. Unlike western paintings, dansaekhwa is characterized by a painting process that accompanies the practice of controlling or emptying one’s mind.

Created through a process of repetition based on meditation and discipline, Kim’s dot paintings took some three months to create, said Paik Seong-lee, a curator of Whanki Museum in Buam-dong, Seoul.

In a diary entry dated March 28, 1973, Kim writes: “Technique is trivial, what makes art is depth of spirit.”

Initiated by Kim, dansaekhwa began to flourish in the 1970s and has come to represent Korean art in the international art market in recent years.

Earlier in his career, Kim also led an avant-garde art group called “Sinsasilpa” in Korea, introducing abstract paintings to the country in 1947 -- two years after Korea was liberated from Japan. Kim, who finished college in Japan, tried to include Korea’s traditional subjects in his abstract paintings such as a moon jar, one of his most beloved subjects in his early years.

A note he wrote in 1964 shows how Kim agonized over the identity of Korea’s modern paintings: “One-third of the 20th century was blocked by Japan, and Korea finally started its own modern art. But 90 percent of those who practice modern art in Korea cannot be trusted because they just bring in Japanese elements.”

Life-time supporter Kim Hyang-an

Whanki Museum, located on a hill in Buam-dong, central Seoul, is largely the result of efforts by Kim Hyang-an, his wife and life-long partner in his artistic endeavor.

“Without Hyang-an’s support, Kim’s artistic spirit would not have existed,” Park Mee-jung, director of Whanki Museum told The Korea Herald on May 21 during an interview conducted at the museum.

|

A photograph of Kim Whan-ki and his wife Kim Hyang-an is hung on the wall inside Whanki Museum. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

Hyang-an encouraged the artist to go abroad to broaden his experiences as an artist, leading to his stay in Paris from 1956 to 1959. In 1963 he moved to New York, where he died of stroke in 1974 at the age of 60. Those years abroad were invaluable in forming Kim’s own artistic philosophy.

It was during his Paris years that he began exploring a poetic approach to his paintings, which became the foundation of his later works -- the dot paintings.

“While staying in Paris, Kim thought deeply about how he could impress people from both the West and Asia, and began to pursue a poetic approach in his art using simple things such as dots and lines,” Park said.

|

Park Mee-jung, director of Whanki Museum, poses in front of Kim Whan-ki’s artworks. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

In a January 1957 diary entry, Kim wrote: “What I felt is the spirit of poem. There seems to be a song in art. There are powerful songs in the works of great masters.”

His wife founded Whanki Foundation in 1979 in New York, five years after Kim’s death to prevent the artist’s works from becoming randomly scattered and to promote his artworks internationally.

In 1992, Hyang-an established Whanki Museum, Korea’s first museum dedicated to a single artist. The museum houses some 2,000 of Kim’s artworks and archives, permanently preserving his works in Seoul as the artist had wished. The Whanki Foundation moved to Seoul in 1989.

“Art museum is the content. No matter how beautiful the building may be, if it has poor contents and does not give deeply impress the visitors, an art museum is nothing,” Hyang-an wrote in a message dated Sept. 23, 1993. She died in 2004.

Kim, who once taught at Hongik University in Seoul, was very interested in guiding young artists. That interest is reflected in the annual Prix Whanki award organized by the museum with the aim of supporting promising young artists. The winner of the award, open to young artists of all nationalists, is given an opportunity to hold a solo exhibition at the museum.

|

Whanki Museum located in Buam-dong, central Seoul (Park Hyun-koo/ The Korea Herald) |

Designed by architect Woo Kyu-seung, the museum building that reflects elements of nature, such as mountains, moon and clouds that Kim considered important, is worth a visit on its own. In fact, some 40 percent of the museum visitors come to see the architecture of Whanki Museum, according to the museum.

Currently shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the museum will reopen June 6 with a new exhibition titled “The Poetics of Kim Whan-ki.” The exhibition showcasing some 200 works by the artist will run until Oct. 11.

By Park Yuna (

yunapark@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] How Gopizza got big in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/20/20241120050057_0.jpg)

![[KH Explains] Dissecting Hyundai Motor's lobbying in US](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/20/20241120050034_0.jpg)