|

People walk across the Gwanghamun Square in Seoul last month amid clear skies with less fine dust concentration. Air quality in terms of fine dust and ultrafine dust concentration significantly improved this year compared to year earlier from the government‘s rollout of seasonal management system and from the coronavirus pandemic disrupting operations of air pollutant-emitting factories in and out of the country. (Yonhap) |

From Mumbai to Beijing to Madrid, the global coronavirus pandemic has brought back clear skies and visibly cleaner air, as a sharp slowdown in human activity has allowed Mother Nature the much-needed time to heal some of her wounds.

Seoul has been no exception. Spring skies were noticeably clearer, compared to those of past years when citizens were advised to wear high filtration masks due to toxic haze blanketing the country for days.

“Weather was so nice this spring that I totally forgot about fine dust problems,” said Byun Jee-hyuk, a resident in Seoul’s southern district of Gangnam.

“Pity that I couldn’t spend much time outside as I was scare of getting infected with the coronavirus,” the 27-year-old added.

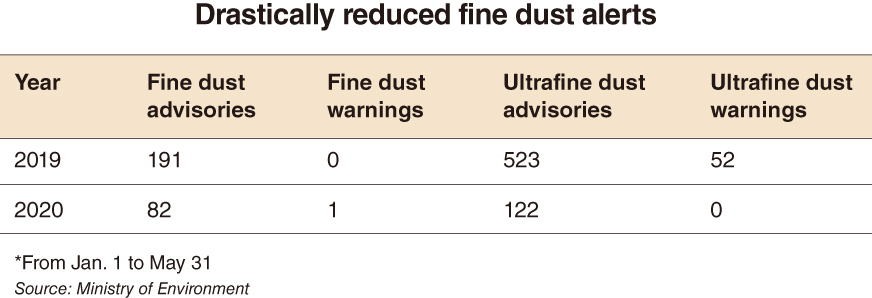

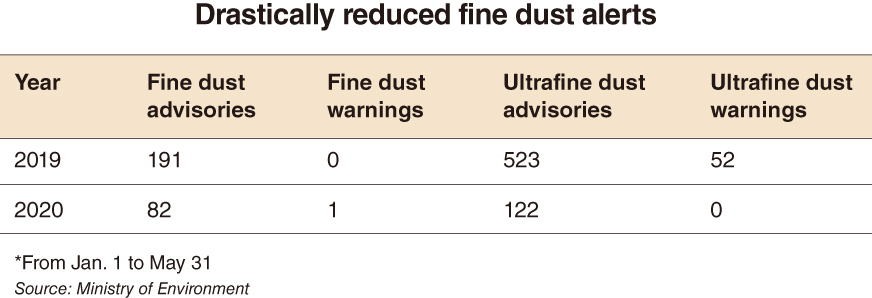

The respite from air pollution is evident in official data.

In the first five months of 2020, the country issued 82 fine dust advisories, 122 ultrafine dust advisories and only one warning for fine dust. In the same period last year, 191 fine dust advisories, 523 ultrafine dust advisories and 52 ultrafine dust warnings were issued. No ultrafine dust warnings have been issued this year.

COVID-19’s silver lining?

Byun, like many Koreans, seemed to believe that the improvement is largely due to epidemic-induced stoppages of industrial areas in neighboring China, which is the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide gas.

“Factories in China stopped for some weeks early this year, and it seemed to me that’s what mainly accounted for our air quality to be so much better this year so far,” he said.

Part of that is true, but Korea’s rigorous enforcement of regulations and programs targeting air pollution also have had a considerable effect in clearing fine dust levels, the Ministry of Environment says.

In a bid to reduce fine dust concentrations in the country during the winter months, when air quality tends to be worst, the government in December launched a set of programs including restrictions on the operation of outdated diesel vehicles, coal power plants, construction sites and other major sources of airborne pollutants.

The seasonal air quality management also entailed a fee hike for public parking lots to encourage the usage of public transportation, as well as more frequent roadside cleanings.

How effective those efforts have been in this year’s improvement in air quality is unclear as of yet, said Kim Jong-ho, an environmental engineering professor at Hanseo University.

“Although it’s too early to say which one played a greater role, it looks clear to me that both external and internal factors deserve credit,” he said.

The external factor, as unforeseen and unprecedented as it has been on a global economic scale, has made Korea’s own efforts less noticeable.

“We would have to wait for the next fine dust-heavy season to grasp how all those efforts are turning out,” he added.

For lasting effect

All this, however, may be short-lived, Kim and other experts warned.

Fine dust concentrations could spike once the virus crisis is over and economies around the world race to make up for the losses. Green initiatives could be pushed aside.

“After the pandemic is over, factories, both in South Korea and China, might run at operating rates exceeding pre-COVID-19 levels to make up for the losses accumulated,” Kim said.

“While they won’t be able to run past their maximum capacity, factories could be running for more hours, and that will be detrimental to the ecosystem.”

Mindful of that, environmentalists are calling for more substantial measures to put the country firmly on the path to a greener economy.

Bolder steps are needed to shift away from fossil fuels to bring about a lasting impact, they said.

“The government started shifting away from coal and fossil fuel vehicles, and that’s good, but we are still not happy with the current level of measures in targeting air pollution,” said Hwang In-chul, climate energy team manager at environment activist group Green Korea.

“The measures must be bolder,” to shift away from traditional energy sources to more sustainable ones, he added.

Even though Korea has been focusing on increasing its proportion of renewable energy sources, coal-based power production still accounted for 41.9 percent of all power produced in the country as of 2018.

Renewable energy accounted for 6.2 percent of all energy produced in the country the same year, up 0.6 percentage point from a year earlier, and the government is eyeing to boost that figure to 20 percent by 2030 and to between 30 and 35 percent by 2040.

Environmentalists also believe that the country should also be more open to eco-friendly vehicle options and shun traditional ones using gasoline and diesel.

“Companies like Tesla are opening new ways for eco-friendly vehicles to be available as price-competitive, practical options,” said Son Min-woo, a clean air campaigner at the Korean unit of global nongovernmental organization Greenpeace.

“The government has been doing well, but what we need at this point are measures and big projects toward changing our society from carbon-based to renewable-based. And maintaining eco-friendly practices with transportation means is just one of many (measures) that are needed for that to be achieved.”

By Ko Jun-tae (

ko.juntae@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)