|

(Yonhap) |

In light of two brutal child abuse cases that grabbed major headlines of Korean media outlets, many angry Koreans are calling for tough penalties on parents who abuse their children under the pretext of discipline.

Earlier this month, police arrested a stepmother in her 40s after her 9-year-old stepson died days after having been found unconscious inside a suitcase. According to the police, the boy was locked up inside the suitcase -- measuring 44 centimeters across and 6 centimeters wide -- for seven hours.

Less than two weeks later, a 35-year-old man was arrested in Changnyeong, South Gyeongsang Province, for brutally tormenting his 9-year-old stepdaughter with his wife, the biological mother of the girl. They allegedly tied the girl up with a metal chain and burned her feet with hot metal chopsticks.

In both cases, the suspected aggressors cited parenting as an excuse for their violence, describing their acts as corporal punishments that had gone too far. Angered citizens fear the court may buy that, as seen in past abuse cases by parents.

In South Korea, spanking has been an acceptable parenting method for a long time, with many people using or familiar with the expression “the cane of love.”

“Many adults in Korea have grown up with some form of corporal punishment, which allowed the tradition to last,” said Lee Yung-hyeock, a professor of police science at Konkuk University.

“More and more people are finding ways to parent without resorting to smacking, but that doesn’t mean that corporal punishment is on track to completely disappear.”

It is this acceptance of corporal discipline that puts children at risk of violence at home, Lee stressed.

“Whether they started beating their kids with the intention of parenting or just physically abused them with corporal punishment as an excuse, we don’t know,” Lee added.

“But what we do know is that letting corporal punishment serve as an excuse for those brutal acts makes more room for children to be in danger of being physically abused, at times even to death.”

According to government data, a total of 132 children were found to have died from child abuse from 2014 to 2018. The yearly count has been mostly in an upward trend from 14 in 2014 to 16 in 2015, 38 in 2016, 38 in 2017 and 28 in 2018.

The number of child abuse cases compiled by the Welfare Ministry stood at 24,604 cases in 2018, more than four times the 5,578 cases recorded 10 years earlier. The statistics only reflect the trend in reported cases, not the actual cases, and could have been affected by the increase in efforts to detect violence.

The Justice Ministry, after the two recent child abuse cases, said it was studying a revision of the Civil Law, which stipulates the parents’ right to discipline their children. Although Article 915 does not say anything about the use of physical force as a means of discipline, it has been interpreted by some as giving legal grounds for corporal punishment.

Taking a step further, the ministry said it is considering including a ban on corporal punishment in the planned amendment to be submitted to the National Assembly by the end of August.

Banning spanking, however, could face hurdles as public opinion is divided on the issue.

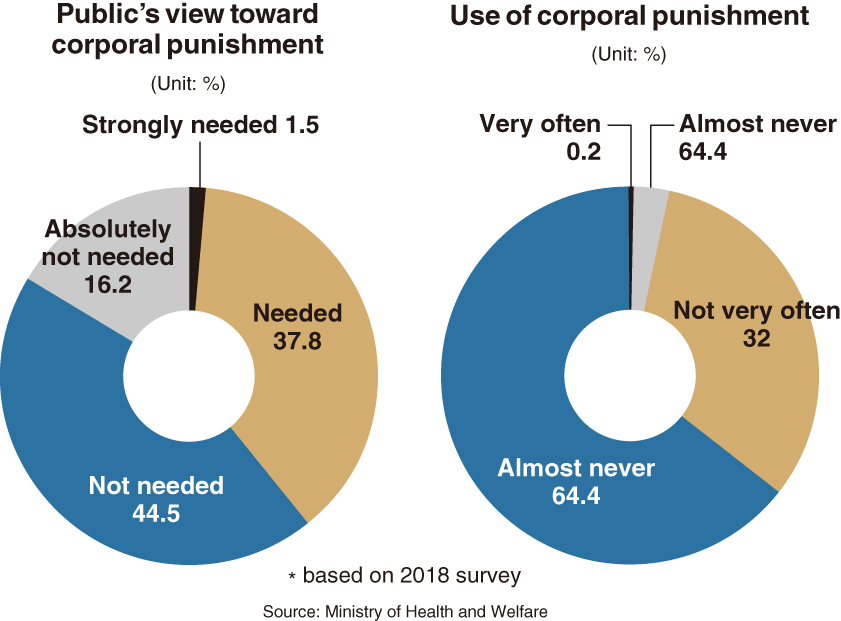

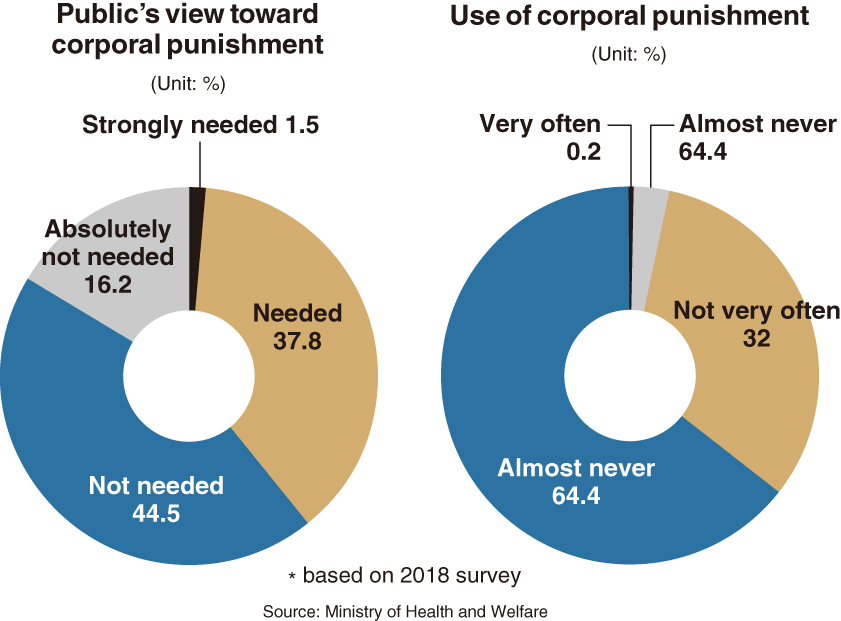

A 2018 survey by the Ministry of Health and Welfare found that nearly 40 percent of parents with underage children looked favorably on corporal punishment as something necessary for good parenting, while the rest were against the use of violence.

A few high-profile cases aside, Korean society as a whole is much more lenient toward parents who abuse their children than other countries, says Na Sang-min, a manager at Save the Children Korea.

“The public sentiment in favor of corporal punishment has waned in the wake of the recent well-known cases, and while that is a good news, there needs to be a legislative support for child abuse to be strictly restricted and to protect the rights of children,” said Na at the local chapter of the child charity group.

Under Korean law, those who commit child abuse and put the victim in a critical condition can be sentenced to more than three years in prison. If the victim dies, the penalty can be raised to more than five years in prison. Suspended prison sentences are possible for both cases.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child has also been one of the forces urging Korea to outlaw any use of physical force on minors. At the moment, 54 countries around the world have legally banned corporal punishment of children, it says.

Some experts say it takes a whole system, not just a single law change, to bring about a real change in the way Korean parents discipline their children.

The government, together with public and private groups and institutions, should build a system to protect children from abusive parents, enable early detection and intervention if and when abuse occurs and educate parents on how to better interact with their children.

“While banning corporal punishment, the government should actively educate and promote non-violent ways of parenting, and this is not a job solely in the hands of the Ministry of Justice,” said Park Myung-sook, a child welfare professor at Sangji University.

“On a greater scope, the government should invest more to bring about a change in people’s perception toward corporal punishment while educating both parents and children on ways to interact with each other.”

For this year, the Korean government assigned 28.5 billion won for child abuse prevention initiatives of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, which accounts for just 0.03 percent of the ministry’s annual budget of 82.5 trillion won.

Police science professor Lee warns real change will be hard to come by without a stronger national commitment.

The country has had shocking child abuse cases before, each time the public erupted with anger. But no lasting change came out from them, as attention quickly faded.

“By next month, there’ll be probably no one talking about those cases, and everything will remain the same as before, like it has been the way for decades in Korea. A flicker of interest doesn’t mean much.”

By Ko Jun-tae (

ko.juntae@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)