Gone are the days when the leaders of the US and North Korea exchanged “love letters” -- or threats of “fire and fury.”

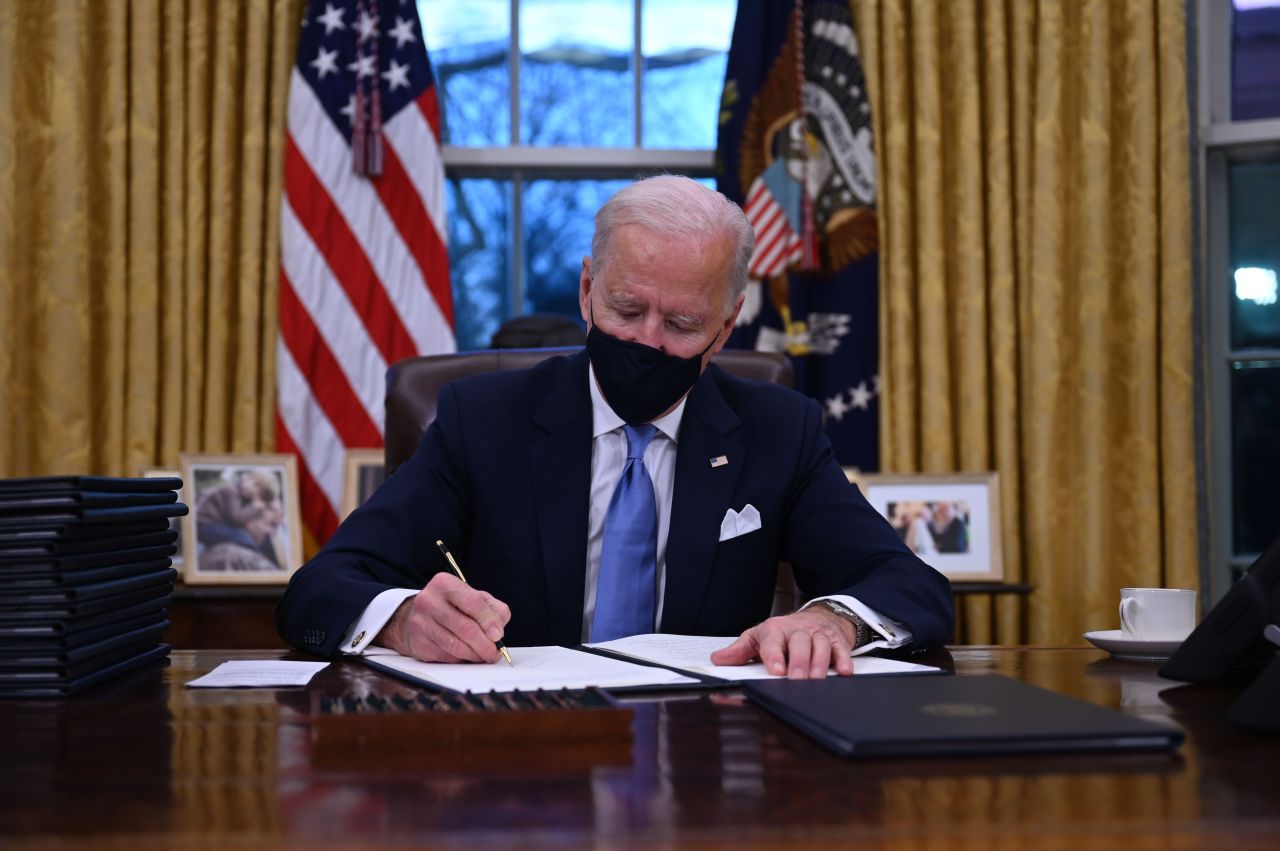

US President Joe Biden took office Wednesday, and the world is now watching Biden to see what actions he will take -- not just unraveling years of Donald Trump’s policies, but how US foreign policy will formulate under the new leader, who declared that “America is back, ready to lead the world.”

North and South Korea are also keeping a close eye on the new administration. Policymakers in Seoul and Pyongyang are trying to figure out how Biden’s White House will approach the Korean Peninsula, where tensions still linger. Many also wonder how the leaders of the three distinctly different countries will fare through the uncertain times ahead.

Biden-Moon: When two liberal presidents meet

“America is Back,” South Korean President Moon Jae-in wrote on Twitter on Thursday, congratulating Biden on his inauguration. Moon struck a hopeful tone, and in a separate congratulatory message sent to Biden he expressed hope of meeting the US president in the near future to build “trust and friendship” and share a “candid dialogue” on issues of mutual concern. Moon vowed cooperation with Biden to bolster the alliance and achieve peace on the Korean Peninsula, as well as to tackle other global challenges, including public health and climate change.

Many observers expect Biden and Moon’s relationship to be as cordial as it can be, underpinned by shared values and objectives. The two won’t necessarily be best friends anytime soon, but after four years of Trump’s alliance-bashing, go-it-alone diplomacy, Seoul appears to be looking forward to a sense of normalcy in bilateral relations and to more predictable policy.

“Biden and Moon can be expected to have professional, even warm exchanges,” said Leif-Eric Easley, associate professor of international studies at Ewha Womans University in Seoul. “Close coordination between their policy teams will be even more important.”

“I think Biden and Moon share a common progressive agenda, both want a strong US-ROK alliance and want to work together on climate change, battling COVID-19 and finding a path forward on North Korea,” said Harry Kazianis, senior director of Korean studies at the Washington-based Center for the National Interest.

“Chemistry between Biden and Moon will be fairly good,” said Ahn Byong-jin, a professor at the Global Academy for Future Civilizations at Kyung Hee University. He added that Biden’s respect for the late President Kim Dae-jung could extend to President Moon, whose life path and policy align closely with Kim’s.

Many are optimistic that Biden’s promise to restore the country’s alliances are a boon for Moon and will allow him to settle some thorny bilateral issues that went unsolved during the Trump era, such as the stalemate in defense cost-sharing talks. Biden’s Defense Secretary nominee Lloyd Austin has vowed to seek an early conclusion to the negotiations, which determine how much Seoul should pay for the upkeep of the 28,500-strong US Forces Korea.

However, friction may come from the different timelines of the leaders in Washington and Seoul, noted Easley.

“Moon is approaching his last year in office and may not be as interested in aligning long-term strategies on China,” he said. “Biden will not be in a hurry to cut deals with North Korea.”

As he comes close to completing his term in May 2022, Moon, who staked his legacy on efforts to invigorate inter-Korean relations, is determined to make some kind of North Korea breakthrough in his remaining time. But his ambition could clash with those of Biden, who just entered office and has a different set of priorities.

The new US president faces mounting challenges on the domestic front that require his immediate attention -- the pandemic, the economic downturn and political divisions, to name a few -- as well as pressing foreign policy matters with China, Russia and Iran.

Moon’s other concern is the possibility of a rift between the two allies, as his push for engagement with the North has not always put him on the same page with Washington, whose major policy objective remains the eradication of the North’s nuclear program. The Biden administration, with key security posts filled with Obama-era veterans, is expected to continue its hard-line stance and dial up pressure on North Korea for denuclearization, observers say.

“A common approach for the DPRK might be difficult as Biden may not want to risk any early political capital or even time on North Korea as Kim does not seem likely to want to engage or give up his nukes,” said Kazianis. “Biden has enough problems on his plate, why add North Korea to that mix if Kim stays quiet, at least for now?”

He stressed that Moon’s task is to convince Biden that Washington should use up what little foreign policy bandwidth it has on Korean Peninsula issues.

Mindful of such concerns, Moon on Monday urged Biden to build upon the achievements from the 2018 Singapore summit agreement between Trump and Kim, in which Pyongyang agreed to complete denuclearization in exchange for security guarantees from Washington. But at a time when Biden is moving swiftly to undo Trump’s legacy, it is uncertain whether the agreement from the first-ever US-North Korea summit will survive.

Meanwhile, Seoul officials have expressed hope for close cooperation with Washington in dealing with Pyongyang, now that both countries have liberal presidents for the first time in two decades. The last time this was the case was during the administrations of former President Kim Dae-jung, known for his “Sunshine Policy,” and President Bill Clinton, from 1998 to 2001 -- widely recognized as a period when the allies worked together and achieved significant progress with the North.

But this could be wishful thinking, says Park Won-gon, professor of international politics at Handong Global University. “The situation has changed since then, especially as the North’s nuclear program has advanced drastically since the Clinton era,” he said “Also, considering Biden, who has witnessed Pyongyang breaking the ‘Leap Day Agreement’ in 2012 as Obama’s vice president, his position toward the regime since has hardened and he is unlikely to trust Pyongyang.”

Biden-Kim: No more flashy summits, personalization

The leaders of the US and North Korea aren’t exactly off to a good start. During the election campaign, Biden called Kim a “thug,” while Pyongyang has previously labeled Biden a “rabid dog.”

Name-calling between the two countries is nothing new. At one point, Trump called Kim “little rocket man,” while Kim slammed Trump as a “mentally deranged US dotard,” before a dramatic turnaround resulted in an unprecedented three summits and the pair eventually “fell in love.”

Such an about-face is less likely to be replicated with Biden, who has criticized Trump’s North Korea policy, saying his headline-grabbing summits only legitimized North Korea and failed to stop the regime from developing more missiles.

Soo Kim, a policy analyst at Rand Corporation and a former CIA analyst, said “personalization” will no longer be a fixture of US-North Korea interactions under the Biden administration. “I would expect to see the US administration keeping a healthy distance between the two leaders -- for the sake of credibility and leverage over the North Korean regime,” she said.

Washington will likely take a more “measured approach,” and try to keep the relations with Pyongyang from going “off the rails,” Kim added. “This likely means no summitry, but also no flagrant statement to stoke tensions with the Kim regime, either.”

Many believe the era of summit diplomacy is over for now under Biden, who said he will meet Kim only on the condition that Pyongyang agrees to draw down its nuclear capacity.

“I don’t see any sort of summit happening anytime soon, letters or a personal connections like Trump and Kim as Biden is much more of a traditionalist when it comes to national security,” said Kazianis. “I see Biden wanting working-level talks and a concrete agreement before walking into a summit -- something Kim might not like as he has gotten used to getting summits without having ironclad deals already negotiated.”

Rand’s Kim agreed, adding that the Biden administration is unlikely to accord Kim Jong-un a summit without having seen “North Korea take measurable and credible steps towards denuclearization and a reduction of tensions on the Korean Peninsula.”

“Kim’s speech at the party congress has made it crystal clear he intends only to build his nuclear arsenal,” she said. “So, prospects for a Biden-Kim summit in this arrangement seem pretty slim.”

During the latest ruling party congress, Kim Jong-un called the US the “foremost principal enemy” of his country, saying the North’s policy toward Washington “will never change, whoever comes into power,” in an apparent message directed to the incoming Biden administration.

He also vowed stronger nuclear deterrence and maximum military power, as well as laying out a wish list of advanced weapons it will procure, a message of defiance against Washington, experts say.

“This is to declare the North a de facto nuclear state and demand the US recognize Pyongyang as a nuclear power. Pyongyang will only consider arms control talks with Washington in the future, but has no intention of denuclearizing,” said Park.

Rand’s Kim expects the North to continue to dial up the pressure on the Biden administration.

“How quickly Pyongyang will increase the pressure remains to be seen and will be determined by Washington’s stance,” she said.

But Pyongyang did not completely shut the door to diplomacy with Washington and has put the ball in Biden’s court, demanding the US withdraw its “hostile policy” first.

One of the regime’s significant gestures may be its recent announcement that it plans to reduce its carbon and greenhouse gas emissions, joining global efforts to tackle climate change, according to professor Ahn.

“Pyongyang is appealing to Biden administration of its interest in climate change and positioning itself as a normalized nation, in mind of Biden’s focus on climate change,” said Ahn. “If the North wants to be recognized as a normal state and to develop trust with the Biden administration, it would need to provide a detailed roadmap to improve human rights as well. Because Biden will definitely require Kim to tackle the North’s humanitarian issue.”

By Ahn Sung-mi (

sahn@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)