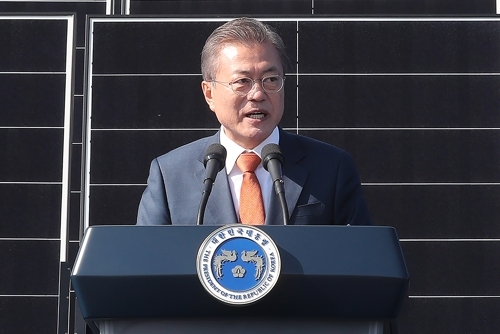

Clean energy, new jobs and a revitalized local economy. President Moon Jae-in’s Green New Deal is billed to serve all these purposes.

Yet, its push for solar energy runs the risk of fattening the pockets of Chinese manufacturers, who in recent years have swamped the local market with cheap solar cells.

An investigation by The Korea Herald has revealed that none of the companies involved in the government-led 5 trillion won ($4.5 billion) project to build a solar farm on the reclaimed land on the country’s west coast have guidelines or incentives to use Korean-made cells.

The Saemangeum photovoltaic project, if completed as planned in 2025, would have a capacity of 2.8 gigawatts. The first stage of the construction for 0.5 gigawatt will begin in the first half of this year, according to the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy.

Of the initial batch of 0.5 gigawatt, the city of Gunsan in North Jeolla Province and public utility firm Korea Midland Power will each build facilities capable of generating 0.1 gigawatt on the ground. Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power, the state-run body that runs the nation’s nuclear reactors, will build a 0.3 gigawatt floating solar power plant.

Less than four months left before the groundbreaking deadline given by the ministry, none of the three parties -- all public entities -- could provide a straightforward answer as to the use of local cells. Converting sunlight into electricity, photovoltaic cells, or solar cells, are the very basic element for a solar energy facility.

“There is no clause in the bidding term that mandates the use of Korean-made cells,” an official at Gunsan said. The city has selected preferred bidders including Korean solar cell manufacturer Hanwha Q Cells and is in the process of choosing the final candidate.

Korea Midland Power gave a similar answer.

“Komipo (Korea Midland Power) is in the process of selecting a developer and it hasn’t been decided yet whether to use Korean solar cells for the project. Also, when we negotiate with bidders, there is no such guideline to demand the usage of Korean cells,” an official there said.

In response to the same question, Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power replied: “It hasn’t been decided whether to require bidders to use a certain ratio of Korean-made cells for the project.”

The domestic solar power industry expressed their frustrations on the absence of such guidelines.

They said the Saemangeum project is a glaring example of how the government is neglecting efforts to nurture the domestic industry, despite touting the Green New Deal’s effects on boosting the local alternative energy sector and creating new jobs.

“President Moon is allowing Chinese cells to dominate even the state-led projects,” said an official from one of the major Korean solar power companies. It draws a stark contrast from what the US is doing to protect its solar industry, the official added.

The penetration of Chinese cells, 10-20 percent cheaper than locally-produced ones, is not a problem only confined to Korea.

The US, under former President Donald Trump, had imposed an “America first” tariff of 15 percent on solar cells and modules from China, which the new Biden administration has so far left untouched.

The Korean government, positioning itself as a champion of fair and open trade in the era of trade wars and sanctions, has no such protection in place for local firms.

There is no readily available data on the share of foreign cells in the market, as the Energy Ministry has so far counted imported cells assembled into modules here as local products.

In October last year, Rep. Han Moo-kyung from the main opposition People Power Party revealed that foreign cells controlled 91.6 percent of the local market as of 2019, according to an analysis he conducted. In the same year, Korea imported 5,666 metric tons of solar cells from overseas, which are enough to manufacture 3.3 gigawatts of solar modules. Korea installed 3.6 gigawatts of solar modules in 2019.

In the same year, official data from the ministry-affiliated Korea Energy Agency puts the ratio of domestic solar modules and Chinese modules in Korea at 78.4 percent to 21.6 percent. As of the first half of 2020, the gap narrowed to 67.4-32.6 percent, allowing Chinese products to breach a 30-percent mark for the first time.

After complaints from industry players for not providing a correct picture of the market, from this month onwards, the agency will begin categorizing solar modules based on the origins of the cells as opposed to their assembly locations, it said.

When asked to respond to the dominance of Chinese cells and the prospect of the Green New Deal further benefiting Chinese cell makers, an energy ministry official said: “The ministry doesn’t have the authority to force private companies to use Korean-made solar cells.”

As for public projects, such as the Saemangeum solar farm, the government could have public utility companies prioritize local goods over imported ones, but that, too, runs the risk of violating international rules set by the World Trade Organization, the official added.

By Kim Byung-wook (

kbw@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)