The Korea Herald is publishing a series of interviews with the lineup of speakers who will discuss solutions to the climate crisis at the H.eco Forum, which is scheduled to be held virtually on June 10 under the theme “We Face the Climate Clock.” -- Ed.

South Korea pledged to go carbon-free by 2050 in October last year -- an ambitious goal for the world’s seventh-largest emitter of carbon dioxide.

But the question remains: How?

To lay out a detailed road map and ensure progress toward achieving the country’s climate targets, Korea launched a 97-member presidential commission on May 29.

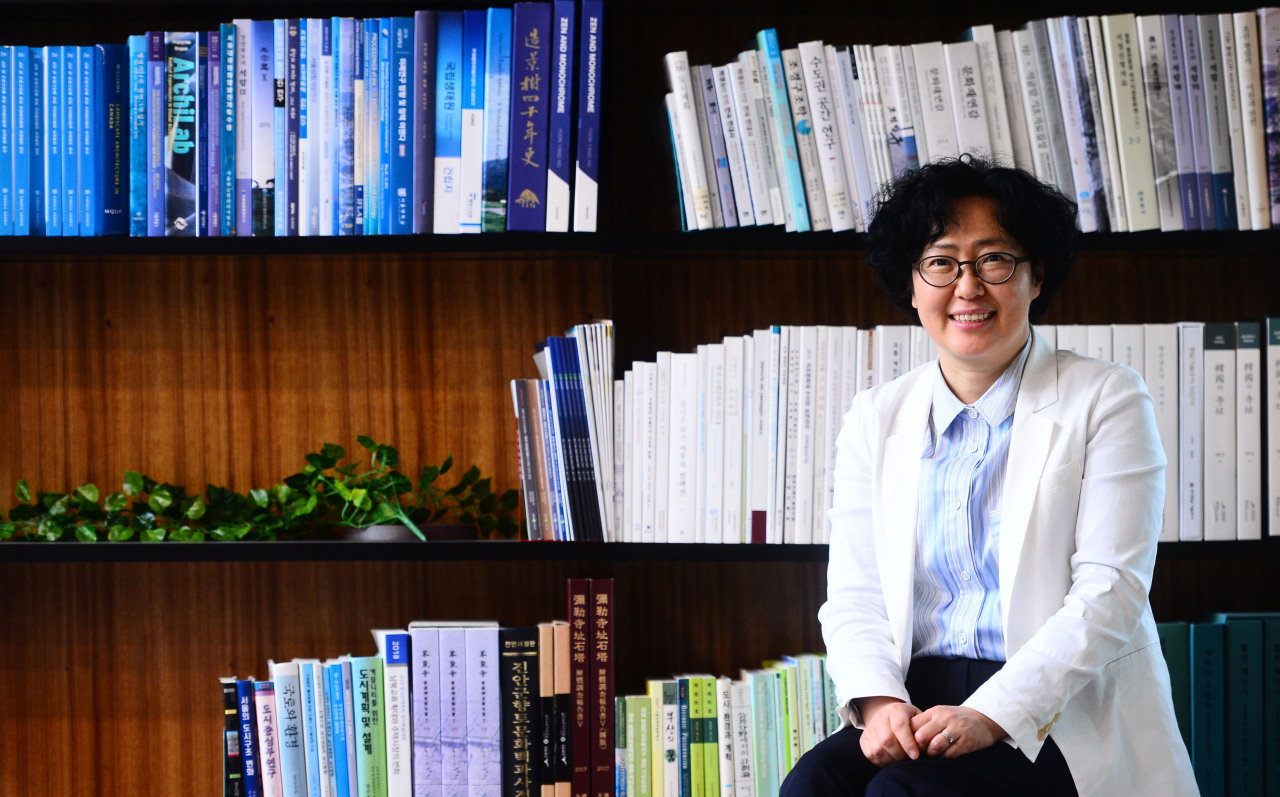

“For an export-driven country like Korea, going carbon-free by 2050 is no longer a question of whether it is possible. We must make it possible and figure out how,” said Yun Sun-jin, co-chairperson of the 2050 Carbon Neutrality Commission, in an interview with The Korea Herald.

As of April, Korea was one of 131 countries that had either set its emissions reduction target at net zero by midcentury or were considering it, amid a growing sense of urgency about the need to keep global temperatures from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius.

“The global economic order and rules are changing. If Korea doesn’t adapt to the changing rules quickly, our economy, our businesses will be adversely affected. That will affect all of us,” she said.

With countries around the globe increasingly considering the introduction of carbon taxes and other carbon-cutting measures, taking a path toward net zero emissions is “not only a matter of our environment, but a matter of our economy and our survival,” Yun added.

The new commission’s most important role is to convince Koreans why climate change is everybody’s problem, why we must cut emissions and how much it costs to meet the climate targets, she added.

Yun, who also teaches at the Graduate School of Environmental Studies at Seoul National University, will be one of the speakers at the H.eco Forum in Seoul on June 10. She will speak about Korea’s road map to net zero emissions.

Co-headed by Yun and Prime Minister Kim Boo-kyum, the commission, comprising 18 government officials and 77 members from the private sector, is the control tower for the country’s carbon neutrality drive.

The commission aims to find common ground among relevant ministries, industries, academia and those affected by the impact of climate change, including laborers and the younger generation. It is responsible for setting out a road map and a timeline for its tasks, mapping out policies, monitoring the implementation of those policies and assessing Korea’s progress in reducing carbon emissions.

For now, one of its priorities is to seek a consensus among different stakeholders and gain endorsement for the country’s climate goals and action plans -- which will, of course, cost money and bring drastic changes to every sector of the country’s economy.

Korea plans to set out different scenarios by the end of June for achieving net zero emissions. Then, within this year it will submit the updated version of the Nationally Determined Contribution and raise its greenhouse gas reduction targets.

“I am aware of civic groups’ criticism that the government is short on details to achieve its climate goals, but we are just beginning our net zero journey,” she said, admitting that the country’s green energy transition was just starting.

It is not an easy task for Korea, she added, as the nation is one of the world’s most carbon-intensive economies and relies heavily on its fossil fuel-powered manufacturing industry. Renewables only accounted for about 6 percent of the country’s electricity production as of 2019.

The focus should be on increasing that figure and lowering the price of renewables, she said.

One of her suggestions is that communities in small cities and in the countryside, which now face shrinking populations, take the lead in the country’s energy transition by hosting renewables infrastructure and providing renewable energy to cities. That way they can generate economic profits and revive regional economies, according to Yun.

To put its ideas into action, the commission, which was set up under the presidential office without any legal framework, should be given legal authority, Yun said.

“There must be a legal basis for the commission’s existence and its role so that the country can consistently and stably advance toward carbon neutrality despite a change of administration,” Yun said, adding that the commission would need the authority to set carbon budgets, oversee progress in cutting emissions and hold accountable those who fell short of meeting the country’s climate goals.

After a public hearing in February, a draft bill was submitted that could serve as the backbone of the country’s climate response. It is still under review in the parliament, and Yun hopes to see it pass later this month.

By Ock Hyun-ju (

laeticia.ock@heraldcorp.com)