|

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un (left) and his younger sister Kim Yo-jong (Herald DB) |

To the North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, his younger sister Kim Yo-jong is a very special figure.

Kim Yo-jong assists Kim Jong-un at close range for official events. She is intimately involved in important international affairs and wields great influence over the politburo.

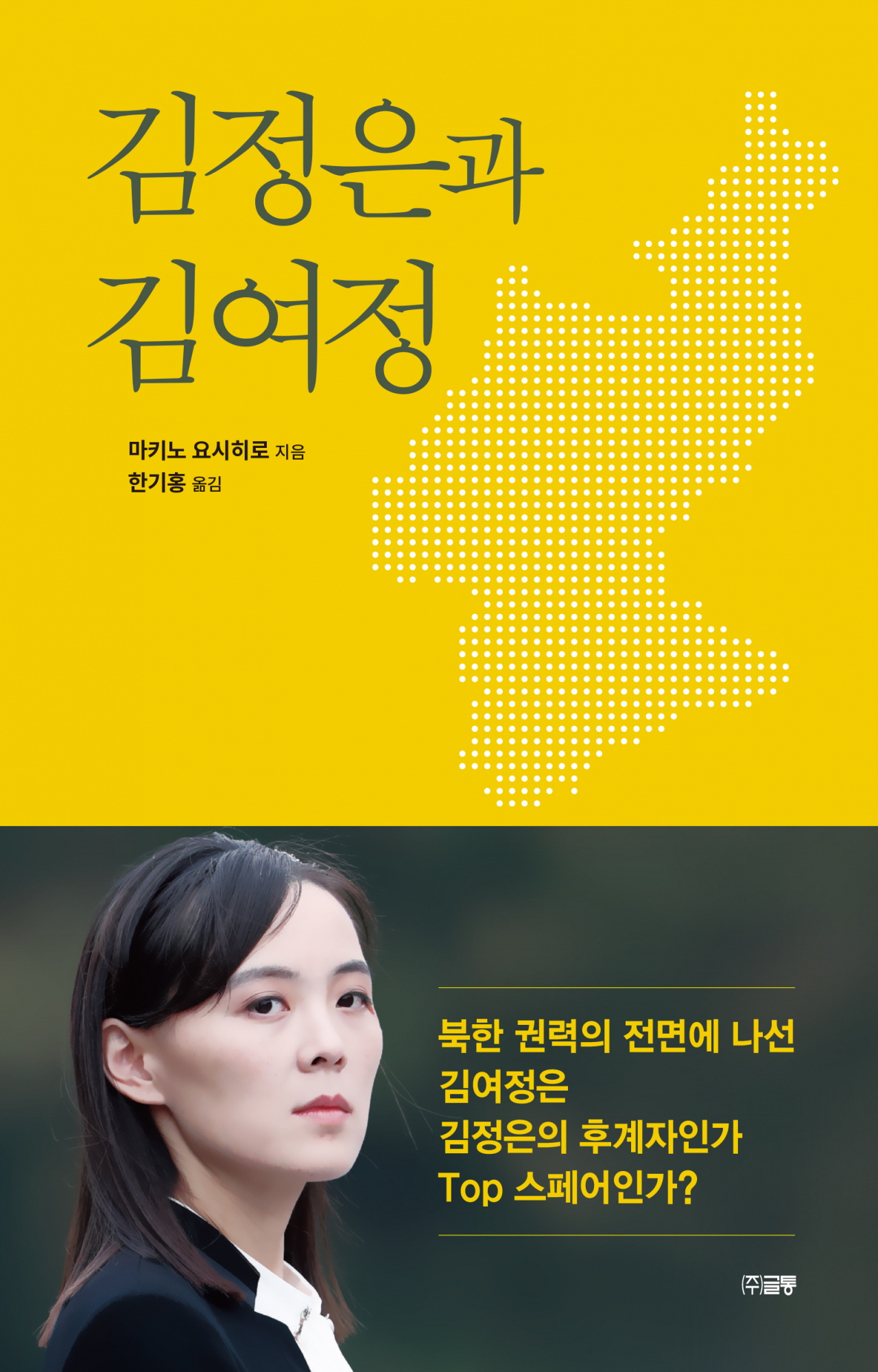

Is Kim Yo-jong a successor to Kim Jong-un? Or a top spare for the Kim dynasty? asked Yoshihiro Makino, a reporter and former Seoul bureau chief of the Asahi Shimbun, one of the four largest newspapers in Japan, in his recently published book titled “Kim Jong-un to Kim Yo-jong.” The Korean edition hit shelves on Dec. 23.

The 326-page book covering North Korea from the 1990s to today offers an interesting inside look at the North Korean leader's family, particularly Kim Yo-jong.

According to the book, Kim Jong-un frequently took women to Koryo Hotel in Pyongyang in the mid-2000s. Angered by the son's behavior, Kim Jong-il grounded Kim Jong-un, but, undeterred, the younger Kim continued to frequent the hotel with women. When Kim Jong-il became furious, it was Kim Yo-jong who intervened and reconciled the father and the son.

Makino also writes that it was Kim Yo-jong who persuaded her father to distribute mobile phones and begin 3G mobile service. Kim Jong-il was reluctant to do so because a mobile phone could be used to track his movements in real-time. But the daughter convinced the then leader that a digital information society will lead to North Korea's development.

The Japanese reporter explains in detail why Kim Jong-un cannot reveal his mother Ko Yong-hui’s identity; the power struggle between Ko and Kim Jong-nam, the eldest son of Kim Jong-il and half-brother to Kim Jong-un; important female figures in North Korean politics; the breakdown of the US-North Korea summit in Hanoi; why and how Kim Jong-nam was assassinated at Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Malaysia, in February 2017.

The book says that when a succession plan was being drawn up after Kim Jong-il suffered a stroke in August 2008, Kim Yo-jong appealed to her father that she wanted to be involved in politics.

Kim Jong-il’s sister, Kim Kyong-hui, however, opposed her niece's participation in politics because she knew that her brother didn’t want women to overshadow men and male supremacy remained strong in the society.

|

“Kim Jong-un to Kim Yo-jong” by Yoshihiro Makino (Geultong) |

The book discusses Kim Yo-jong’s political style, how she made her way to the political forefront after Kim Jong-il’s death and why she has become a special figure to the current North Korean leader. Mainly, Kim Jong-un has no one to trust and is in an unstable health condition, Makino writes.

The author also highlights how successive South Korean administrations dealt with North Korea.

The Lee Myung-bak administration (2008~2013) once asked Kim Jong-nam to seek asylum in Korea but Kim declined. The Park Geun-hye administration (2013~2017) planned a clandestine operation to eliminate Kim Jong-un after North Korea’s fourth nuclear test in January 2016, but the plan was never implemented as Kim tightened his defenses.

Makino worked as a correspondent in South Korea for the Asahi Shimbun from 2007 to April 2019 and specializes in North Korean issues.

In the author’s note, Makino shares news from the Korean Central News Agency, the state news agency of North Korea, that specifically call him human trash and his articles unfounded. In June 2018, during the Moon Jae-in administration, the reporter was banned indefinitely from entering Cheong Wa Dae. He heard from acquaintances that the administration officials were upset with his articles that were critical of the government.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)