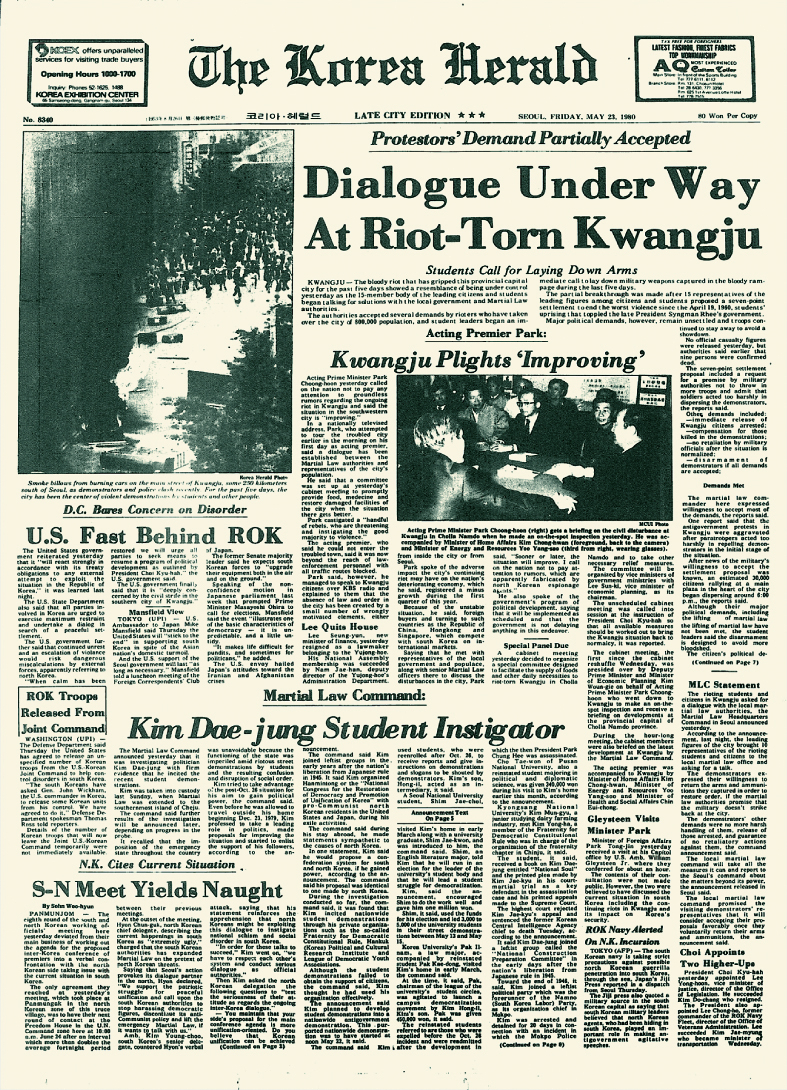

“Dialogue under way at riot-torn Kwangju,” reads the top headline on the front page of The Korea Herald’s May 23, 1980 edition.

It says the “bloody riot that has gripped this provincial capital city” was on the verge of control, with representatives of the demonstrators beginning talks with government authorities. According to the article, authorities accepted several demands by the “rioters who have taken over the city of 800,000,” and the student leaders called out to protesters to lay down the military weapons they seized during the “bloody rampage.”

Acting Prime Minister Park Choong-hoon urged the nation not to pay any attention to “groundless rumors” about Gwangju, adding that the martial law command is investigating opposition politician Kim Dae-jung on suspicion of instigating the student demonstrators. It also appears that nine people were confirmed dead during the “students’ uprising” at the time.

Looking back over four decades later, it is alarming to see how little the truth was reflected on the newspaper page. It is widely recognized now that the blood was on the hands of the government, which has been held responsible for hundreds of deaths during the blood-stained crackdown on pro-democracy protests that went down in Gwangju.

|

Front page of the May 23 edition of The Korea Herald (The Korea Herald) |

From the military turning guns on unarmed civilians to the newspaper failing to grasp the truth, the South Korean system failed in more than one way, the reasons for which can be traced back to the junta and its leader who is still despised by many Koreans today: Chun Doo-hwan.

December coup in 1979, and tension before bloodbath

On Oct. 26, 1979, what had been unthinkable happened. President Park Chung-hee -- a dictator for nearly two decades -- was assassinated by his intelligence chief Kim Jae-gyu. Less than a month after Park’s death on Dec. 12, Army Maj. Gen. Chun Doo-hwan seized control of the military via a coup, paving the way for his eventual rise as the country’s next dictator.

After the coup, the administration of interim President Choi Kyu-hah remained for some time. Although powerless to stop Chun's ascent to power, Choi did manage one significant act -- pardoning or reinstating several of the late tyrant's political rivals, including Kim Dae-jung.

With Park gone and the military junta seemingly fallen, pro-democracy demonstrations erupted across the country, led mostly by college students. Martial law command deployed troops in major cities in early May 1980, which turned out to be prerequisite for the May 17 coup by Chun where he finally gained full control of the nation. Pro-democracy campaigners were arrested again -- including Kim Dae-jung.

The May 16 edition of The Korea Herald devoted a full page to a story titled “Tens of thousands of students demonstrate in nation’s streets” to deliver the news of the situation. According to the article, 40,000 to 50,000 university students took to the streets in the nation’s capital and most populous city, demanding the end of martial law.

Kim's arrest sparked outrage across many regions, but nowhere as severe as in Gwangju and the North and South Jeolla provinces. As a Jeolla native, Kim was highly respected by many residents of the southwestern region, who felt that they had been unjustly discriminated against during the reign of the Gyeongsang-native President Park.

The aforementioned story conveys that an estimated 16,000 people from universities in Gwangju had taken to the streets. The figure is a testament to how angry Gwangju was, considering the city’s population was less than one-tenth that of Seoul.

With the military breathing down their necks, student bodies of 24 universities in Seoul on May 16 agreed to temporarily cease protests on May 16. The May 15 edition of The Korea Herald featured a front-page story titled "Protest march off campus to be dealt with by law," which highlighted the stern warnings issued by the Education Ministry against demonstrations.

But Gwangju was not going to back down. An estimated 30,000 residents and students gathered that day in front of the provincial government office to protest.

According to the May 18 Institute at Chonnam National University, while protests in Seoul and other cities had somewhat subsided, the atmosphere in Gwangju was starkly different. They were still gripped by the joint protests of some 100,000 students across 30 universities that took place at Seoul Station on May 15.

On May 16, ominous scenes began to appear, such as a convoy of military vehicles entering the city via freeway.

|

A May 23, 1980 file photo shows the military in the outskirts of Gwangju, cutting off the road leading to the city. (The Korea Herald) |

Fiasco at Gwangju, but media sings different tune

In 2017 film “A Taxi Driver” about the May 18 Uprising, there is a scene where the protagonist -- after having been through hell in the city -- is baffled at the calm of neighboring townsfolk, who have no idea about the situation happening in Gwangju as they celebrate Buddha’s Birthday.

This bitter irony is reflected in the May 21 edition of The Korea Herald, which devoted nearly an entire page to the merry celebration of the national holiday without so much as a mention of the massacre taking place in Gwangju.

Testimony confirms that paratroopers dispatched to Gwangju brutally assaulted and arrested protesters, but resistance only grew stronger as thousands more joined the demonstrators, who initially were mostly students.

On May 20, the Army enforcing martial law cut off all landline connections between Gwangju and other cities, completely isolating its people from the outside world. The same day, the military opened fire on civilian protests.

While exact numbers are unclear, it is widely believed that the 10-day protests and the bloody crackdown resulted in at least several hundred deaths.

Earlier this month, a grandson of Chun publicly denounced the late dictator as a mass murderer, saying he was to blame for lives lost in Gwangju in 1980. The comment resonated across the nation, as Chun Doo-hwan himself never accepted responsibility or apologized for what happened even to his death in 2021.

None of the military brutality made the headlines.

The May 21 edition told how the UN denounced North Korea’s shooting at the DMZ, how Kim Jae-kyu -- Park’s assassin -- had been sentenced to death and how the Cabinet resigned en masse to take responsibility for the “unprecedented serious disturbance,” but failed to mention that this meant soldiers were killing citizens.

The May 23 edition did not say that the soldiers shot to kill during their standoff two days earlier, as protesters by then had started to arm themselves, and that over 50 protesters were killed, including a pregnant woman.

None of the Korean media were able to report the truth -- the result of media control issued by the junta that had strictly controlled traffic and information in and out of Gwangju. On May 19, reporters from a handful of newspapers across the country campaigned to refuse printing distorted facts about the situation, only to be trampled by Chun in turn.

Park Jong-ryul, a professor of media and communications at Gachon University, said the fight for press freedom by reporters lost its momentum when the junta expanded martial law to the entire nation and several senior members of the Journalists’ Association of Korea were taken into custody.

“The junta’s media control and screening were strengthened after the May 17 measures, particularly concerning reports about the Gwangju Democratization Movement. Censors under the martial law command controlled the media by erasing all stories related to Gwangju,” he said in a recent presentation at the Seoul Press Club about the media crackdown of the 1980s.

According to national media, Gwangju was in a state of anarchy by “rioters,” some of whom were instigated by the likes of Kim Dae-jung and others by North Koreans. The March 20 edition of The Korea Herald carried a statement by then-President Choi about how “some politicians, students and workers have caused anarchic situation where social confusion, disorder, demagogue and destructive acts have become the order of the day.”

With local media silenced by menace, it was German journalist Jurgen Hinzpeter and his sound technician Henning Rumohr who managed to notify the world of what was happening in Gwangju. The aforementioned “A Taxi Driver” tells the story of how cab driver Kim Sa-bok helped the pair sneak in and out of the fortified city.

It is worth noting that many members of the South Korean media continued to fight Chun’s iron-fisted rule well into the 1980s, being tortured and sacked along the way. It was a local reporter who reported the death of a Seoul University student that triggered nationwide pro-democracy protests in 1987, a movement that finally gave the people the right to vote for their own president after Park Chung-hee had taken it from them back in the 1970s.

South Korean journalism has had several moments of pride throughout the country’s history, but May 1980 was not among them. The pages and the stories that remain are a record of how members of the country’s media failed to report the truth, and the shame and horror of the unjust military violence that blocked them from doing their jobs.