|

People run away from police firing tear gas during a protest held in front of the Seoul City Hall in this file photo from June 1987. (Herald DB) |

After weeks of massive protests, the South Korean public finally got what it demanded.

In late June of 1987, the junta hoisted a white flag and proposed a constitutional reform for direct presidential elections.

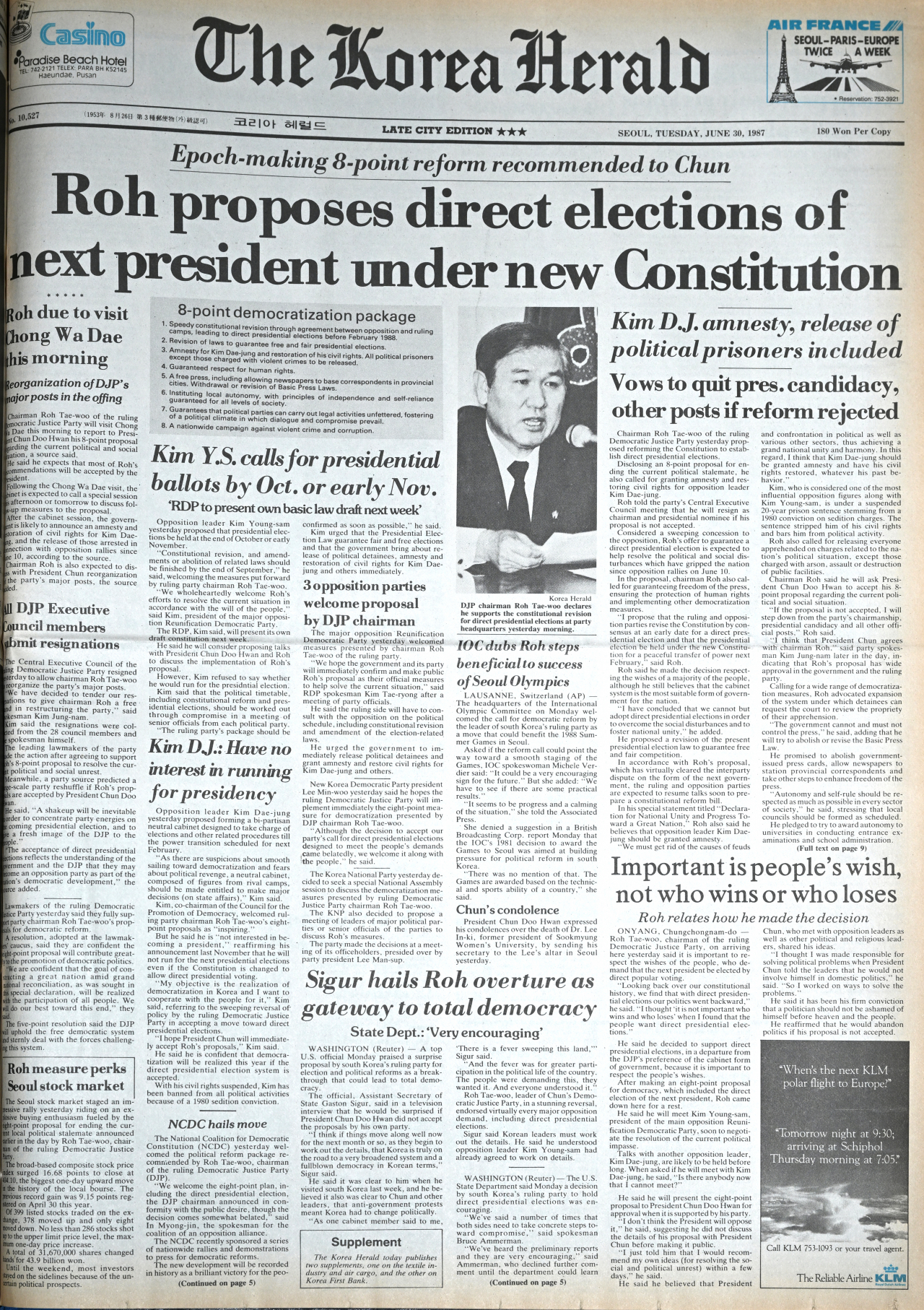

“Roh proposes direct election of next president under new Constitution,” reads the front-page story of The Korea Herald's June 30, 1987, edition, signaling the dawn of a new era for a nation that had been under dictatorship for decades.

Roh in the headline is the late former Gen. Roh Tae-woo, who was dictatorial President Chun Doo-hwan’s closest friend, right-hand man and successor apparent. Roh at the time was also chairman of the then-ruling Democratic Justice Party.

His open proposal of an eight-point reform to Chun, as covered in the article, is recorded as one of the most important political moments in Korea’s modern history, widely touted as a victory for the people.

However, while it laid the foundation for a democratic Constitution, the reform did not instantaneously transform South Korea into a truly democratic nation.

In December that year, South Koreans went to the polls in the nation’s first direct presidential election since 1967. The man elected was none other than Chun’s partner-in-crime, Roh. It wasn’t until the eventual election of the runner-up Kim Young-sam in the 1992 election that the military regime and its leaders got their comeuppance, and the country confronted the legacies of the dark era brought on by the dictatorships.

It was a reminder that things would not be all sunshine and roses after a groundbreaking reform. But at least in the early summer of 1987, things looked like it would be, especially considering the perilous journey the young country had undertaken to reach that point.

|

The June 30, 1987, edition of The Korea Herald |

Groundbreaking compromise

The year 1987 was among the most turbulent years for South Korea's political and social landscape.

Public patience had reached its breaking point under Chun's iron-fisted rule, and in January, the regime's torture, killing and subsequent cover-up of a student activist provoked an eruption of public fury.

Yet, Chun wouldn’t budge. In April he ordered a halt in all talks on constitutional changes, rejecting the people's demand for direct presidential elections.

Millions of citizens took to the streets in what was later called the June Democratic Struggle to demand that the military strongman step down. Less than a month into the protests, the junta government finally yielded, as Roh -- the regime's de facto second-in-command -- suggested the reform that Chun eventually accepted.

The top story of The Herald shows that both the international community and the opposition welcomed the decision, particularly one that granted amnesty to the ruling party's rivals, including democracy fighter and former presidential candidate Kim Dae-jung.

Kim, along with Kim Young-sam, was one of the most high-profile politicians in the opposition, and had been targeted on several occasions by the administrations of Chun and his dictator predecessor, Park Chung-hee. This included a death sentence on false accusations of treason and insurrection, with relation to the May 18, 1980, Gwangju Uprising.

On July 1, 1987, The Herald reported that Chun was "certain to endorse Roh's 8-point democratization formula,” and that the opposition had formed a seven-man panel for constitutional amendment. The ninth amendment of the Constitution was finalized and proclaimed by October, and it remains the last amendment to date.

|

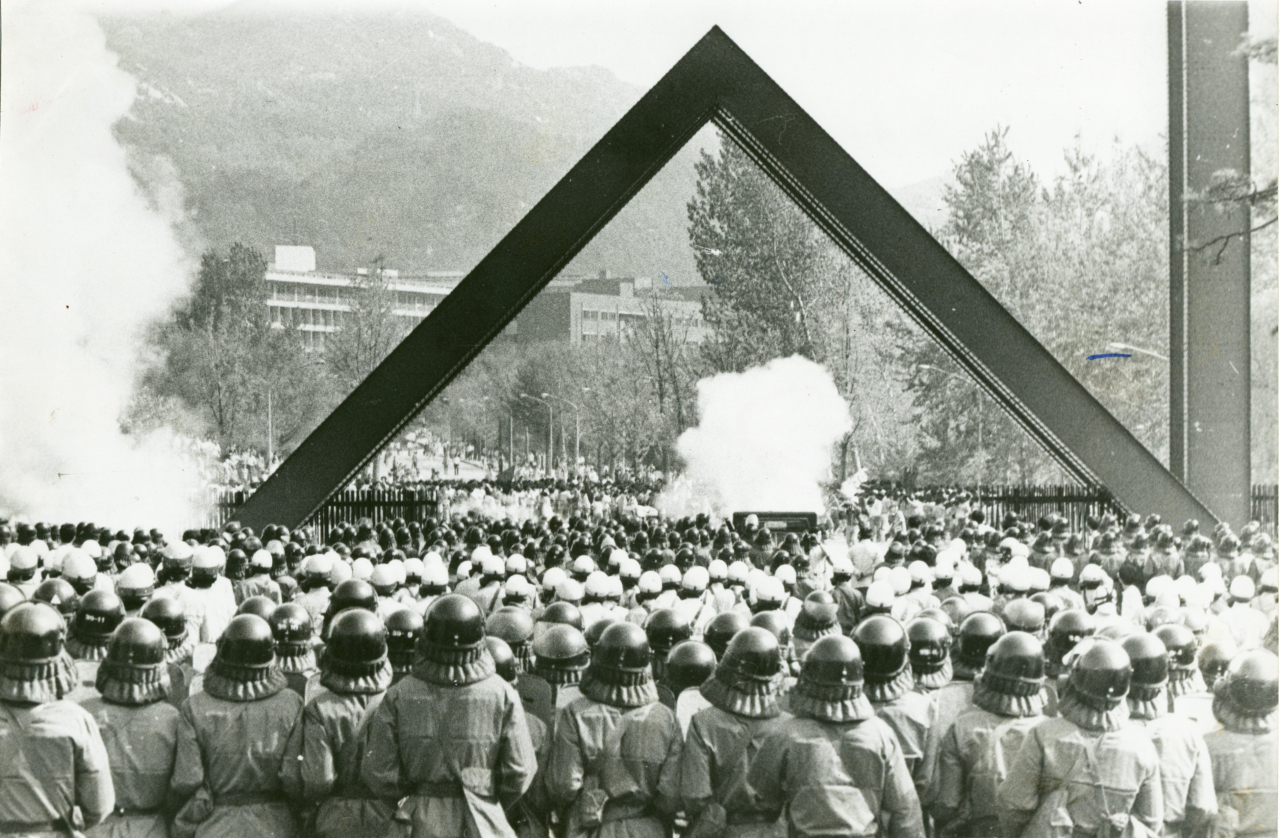

Student protesters at Seoul National University face off with the police in front of the university's front gate in Gwanak-gu, southern Seoul, in this May 7, 1986 file photo. (Herald DB) (Courtesy of the Korea Democracy Foundation) |

|

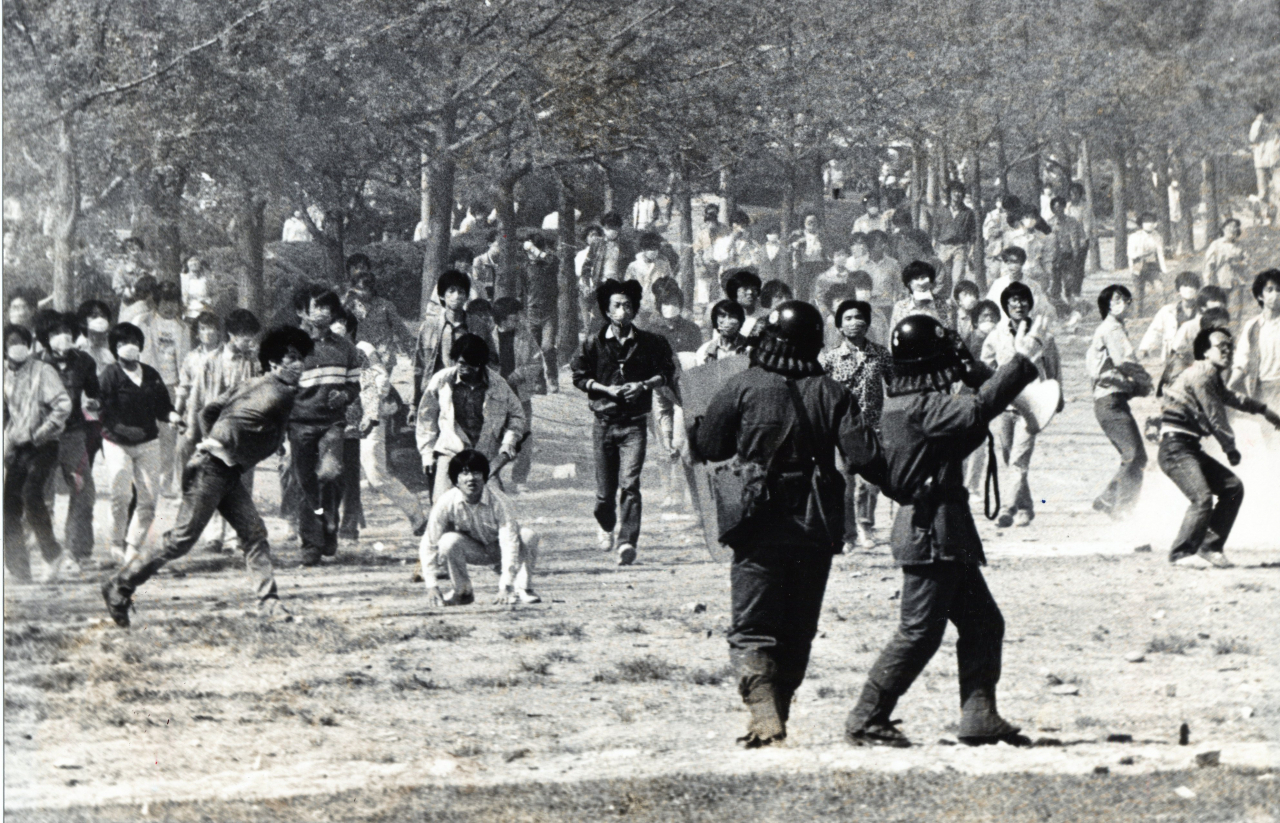

Students of Yonsei University participate in a pro-democracy protest in May 6, 1986, in this file photo. (Herald DB) |

Several testimonies have emerged since then, presenting conflicting accounts regarding the origins of the June 29 proposal.

Lingering questions persist about whether the compromise truly stemmed from Roh's personal "determination" or if it was a strategic move by Chun to place Roh in the spotlight, allowing his trusted aide and friend to assume power and safeguard his interests.

Among them are a compilation of handwritten memos by Kim Yong-gab -- Chun's senior secretary for civil affairs at the time, which strongly indicate the significant involvement of Chun in the process.

One memo dated June 18 -- a little over a week into the massive, nationwide wave of pro-democracy protests -- details Kim’s report to Chun, which implies that the junta knew that the end was near.

Kim shared his view of the political situation with the president: It would be impossible for the administration to win back the public's trust, or for the ruling party to pursue political actions.

As for a direct election, Kim said that it would present a chance for Chun to be “recorded as a great, peaceful president in the nation's history,” since it would be the first time a South Korean presidency was passed on to the next president peacefully through a proper election.

Path to democracy littered with tribulations

The minutes of the meeting by the National Coalition for Democratic Constitution -- an umbrella group of opposition politicians, civic activists and student groups working against the Chun regime -- show that the coalition viewed the June 29 Declaration as “the military dictatorship’s defeat” but that it is only a “20 percent victory” and they must keep the regime in check.

But while Koreans relished their victory and anticipation for a long-sought democracy, signs of fissures in the panopposition coalition were apparent. One of the stories in the June 30 edition was titled, “Kim D.J.: Have no interest in running for presidency,” and detailed how Kim Dae-jung wanted to form a “partisan-neutral Cabinet” with Kim Young-sam. But as the nation would eventually find out, the two Kims would fail to reach a compromise in a united campaign against Roh.

|

Roh Tae-woo, then-chairman of the ruling Democratic Justice Party, announces his constitutional reform proposal that includes a direct presidential election in this June 29, 1987, file photo. (The Korea Herald) |

When the smoke cleared on election day, Dec. 16, 1987, the military dictator's party had retained its leadership with Roh winning 36.6 percent of the votes. Kim Young-sam won 28 percent and Kim Dae-jung won 27 percent, leaving many to wonder, “What if?”

The two Kims eventually became successive presidents of South Korea. Kim Young-sam served first in 1992, and then Kim Dae-jung in 1997.

Aftermath

Under the Kim Young-sam administration, the two military generals who ruled the country -- Chun and Roh -- were arrested and tried for their involvement in the 1979 military coup that gave Chun power, the bloody crackdown by the government on the pro-democracy protests in Gwangju in 1980, along with other allegations of corruption.

Chun was sentenced to death and Roh to lifetime in prison, but the two would be pardoned in 1997 by then-President Kim Young-sam following the proposal of President-elect Kim Dae-jung.

Some conservative politicians, including Rep. Chung Jin-suk of the current ruling People Power Party, have attempted to paint Chun as a leader who put aside his own rights for the people’s demand. Rep. Chung made the remarks while paying respects to him last year on the one-year anniversary of his death. But to this day, Roh and Chun remain among the most unpopular presidents in the country's history.

In October of 2021, days after Roh's death, Gallup Korea conducted a survey on 1,000 adults about what they thought of Korea's former presidents. Some 73 percent of the respondents disapproved of Chun, compared to Roh's 52 percent. The two were the two least respected leaders.

The 1987 revision of the Constitution, still intact today, restricts the presidency of South Korea to a single term lasting five years. It was a measure to prevent the emergence of another dictator in the country.

However, as democracy matures and a peaceful transition of power becomes the norm, there is talk about revising it to allow the nation leader to seek a reelection.

Although there is consensus among the public that it is time to revise the Constitution, the process of amendment has proven to be arduous so far, with rival parties engaging in political calculations to advance their own interests.

|

People read newspaper extras carrying the news of the June 29 Declaration by Roh Tae-woo in this June 29, 1987, file photo in Myeong-dong, Seoul. (Herald DB) |