|

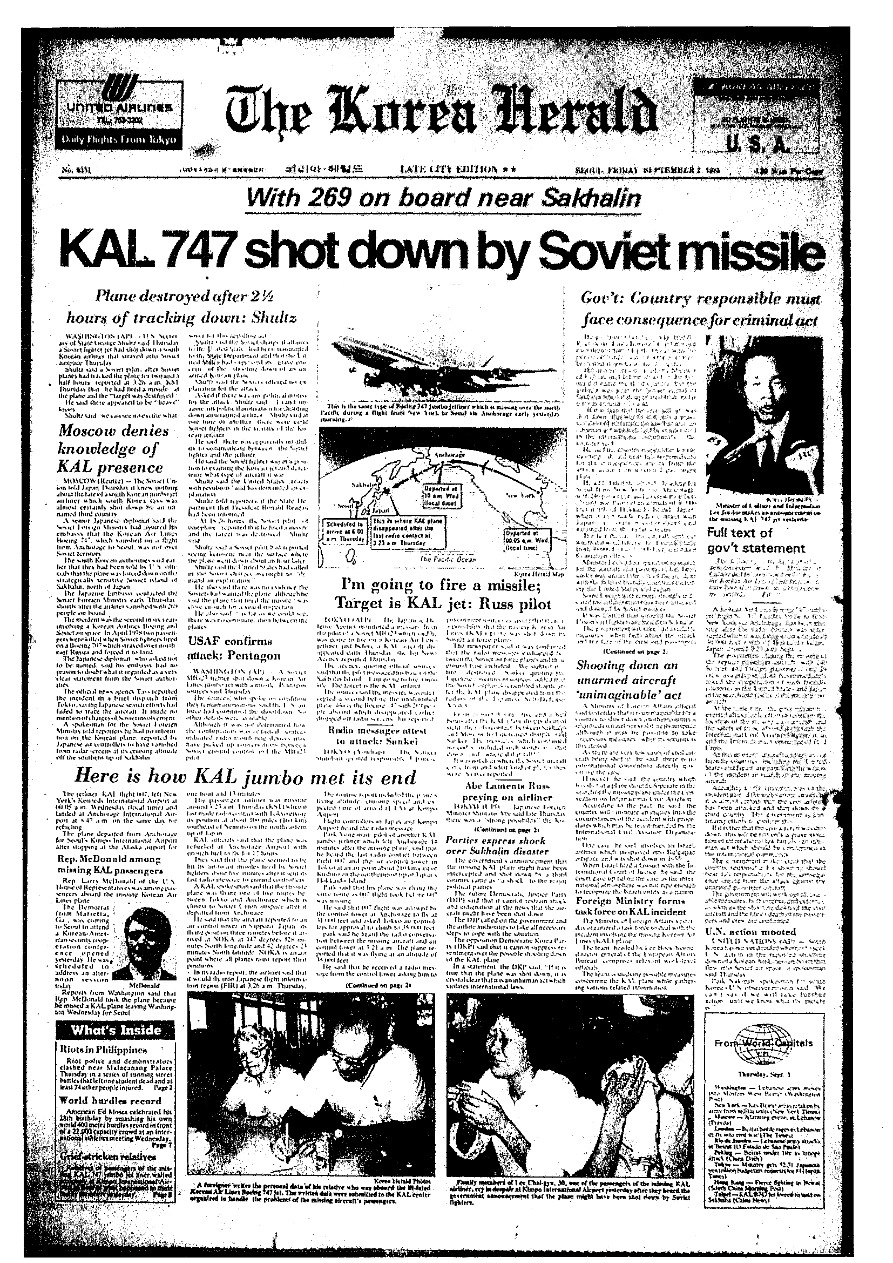

Sept. 2, 1983 issue of The Korea Herald. |

On early Sept. 1, 1983, a Soviet interceptor shot down Korean Air Flight 007 en route from New York City to Seoul via Anchorage. All 269 passengers on board were killed as the aircraft crashed into the sea near an island west of Sakhalin, Russia.

The Soviets had mistaken the Boeing 747 airliner for a US spy plane as it drifted off course and flew through prohibited Soviet air space.

It was one of the deadliest events of the late Cold War.

The Soviet Union initially issued a short statement saying that, as an unidentified aircraft intruded its airspace, its fighters tried to get it to land but it didn’t. Eight days after the incident, the Soviets admitted to shooting down the aircraft, claiming it was inevitable as there was a possibility that it was a US reconnaissance plane.

A similar incident had happened five years before in 1978.

Korean Air Flight 707 with 110 passengers onboard flew off course and into Soviet airspace on its way from Paris to Seoul via Anchorage. It was shot by the same type of Soviet fighters, and made an emergency landing. Two passengers were killed and 13 were injured.

As for KAL007 in 1983, the Soviets recovered its black boxes and remains shortly after the aircraft fell into the sea, but didn’t release them until nine years later, after the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991.

In 1992, Russia’s new president, Boris Yeltsin, made public the Soviet memos discussing the shootdown and subsequent sea search for the wreckage, releasing the black boxes later that year.

Flight into danger zone

It was a time when the US Air Force RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft, which looked like civilian aircraft, regularly patrolled near Soviet territory to spy on the Soviet defense system. But they normally didn’t cross the Soviet border.

The US was expecting the Soviet Union to conduct a missile test later that day, and this missile was projected to land near the Petropavlovsk Navy Base.

KAL007 flew at a magnetic heading of 245 degrees shortly after leaving Anchorage, most likely due to navigational error, making it appear to be on direct course to this nuclear submarine base.

When the aircraft entered Soviet airspace, Soviet commanders ordered Sukhoi Su-15 fighters from a nearby air base to intercept the plane.

The KAL007 pilots, unaware that the Soviet fighters were flying alongside them, called the Tokyo Air Traffic Control to seek permission for a step-climb, or a series of altitude gains to improve fuel economy during the end phase of a long flight.

When the KAL007 began moving higher, the Soviets perceived it as the American spy plane taking action to avoid their plane reach, and decided they weren't going to let it leave the Soviet airspace.

Gennadi Osipovich, the pilot of the Soviets’ Sukhoi Su-15 fighter that fired the air-to-air missiles, later said he could see the Boeing 747 plane with double-decker windows which military cargo planes don’t have.

“I didn’t understand why. What kind of plane is this? But I didn’t have time to think. I had to do my work. I signaled the international code to the pilot of that plane that he violated our airspace, but there was no response from his side,” Osipovich said in an interview in 1988.

At 3:26 a.m. Tokyo time, Osipovich fired two air-to-air AA-3 missiles, fragments of which hit the rear of KAL007, destroying three of its four hydraulic systems.

The plane reportedly flew another 12 minutes before crashing into the sea off the island of Moneron, west of Sakhalin.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) said in its initial investigation in 1983 that the violation of Soviet airspace was accidental.

The report included a Soviet government statement that “no remains of the victims, the instruments or their components or the flight recorders have so far been discovered,” which later turned out to be untrue according to Yeltsin’s release of the Soviet memos in 1992.

In addition to adopting a resolution condemning the Soviet Union for the attack, the ICAO made an amendment to the Convention of International Civil Aviation that reads: “The contracting States recognize that every State must refrain from resorting to the use of weapons against civil aircraft in flight and that, in case of interception, the lives of persons on board and the safety of aircraft must not be endangered.”

In 1993, the ICAO revised its report based on new evidence from Russia including transcripts of communication among Soviet air defense command centers on Sakhalin Island.

“The USSR command center personnel assumed that KE 007 was a US RC-135 aircraft. KE 007’s climb from FL 330 to FL 350 during the time of the interception over Sakhalin Island was interpreted as being an evasive action, thus further contributing to the USSR presumption that it was an RC-135 aircraft," the ICAO report reads.

“No attempt was made by the USSR to contact the crew of KE 007 by radio. ... It was not possible to assess the distance of the interceptor aircraft from the intruder nor their relative positions when the interceptor's lights were flashed and the cannon fired.”

The ICAO said that “the time factor became paramount as the intruder aircraft was about to coast out from Sakhalin Island,” and therefore “exhaustive efforts to identify the intruder aircraft were not made.”

Tragedy’s aftermath

South Korea, which at that time had no diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and was not a member of the United Nations, could only rely on information delivered from its allies -- the US and Japan.

The Seoul government initially issued a statement saying the KAL flight was brought down by “a third country.” After the US government confirmed that a Soviet fighter shot it down in a press conference, then-President Chun Doo-hwan made an announcement on Sept. 2 about what had happened, denouncing Moscow for the atrocity and called on it to take responsibility.

The Sept. 2, 1983, issue of The Korea Herald carries multiple articles titled “KAL 747 shot down by Soviet missile;” “Moscow denies knowledge of KAL presence;” “Gov’t: Country responsible must face consequence for criminal act;” “Here is how KAL jumbo met its end;” and “Lost passengers’ kin in utter despair.”

Headlines on the Sept. 3 issue include “UNSC session today on KAL tragedy;” "Chun: Downing KAL jet utterly inhumane act;” “KAL incident touches off waves of raw rage, grief,” “Nationwide rallies decry Soviet atrocity;” and “General public calls for strong int’l sanctions against Soviets.”

On Sept. 7, a joint memorial service for the deceased was held in Seoul. Some 100,000 people gathered at the tearful ceremony which was broadcast live nationwide.

|

Crowds rally at the joint memorial service for the victims of KAL007 at the Seoul Stadium on Sept. 7, 1983. |

|

Bereaved families mourn at the joint memorial service. |

|

Bereaved families mourn at the joint memorial service. |

Although there were no official diplomatic ties, there had been unofficial contact between South Korea and the Soviet Union, which were stalled for months following the shootdown.

Korea also boycotted international sports events in the Soviet Union.

But while it called on Moscow to take responsibility, Seoul couldn’t afford to antagonize the entire Eastern European bloc ahead of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, so it decided not to ban the entry of the Soviet delegation for the 70th Conference of the Inter-Parliamentary Union held in Seoul in October 1984. Unofficial talks between the two countries were resumed.

Among the passengers of KAL007 were 62 American citizens, including Congressman Lawrence P. McDonald. The US had the second-highest number of casualties after South Korea, while Japan had 28 victims.

Part of the Ronald Reagan administration’s response to the incident was the extension of the Global Positioning System, originally developed for military use against the Soviet Union, to wider civilian use. The GPS tech assisting civilian air traffic was a key step toward safer flights.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)