|

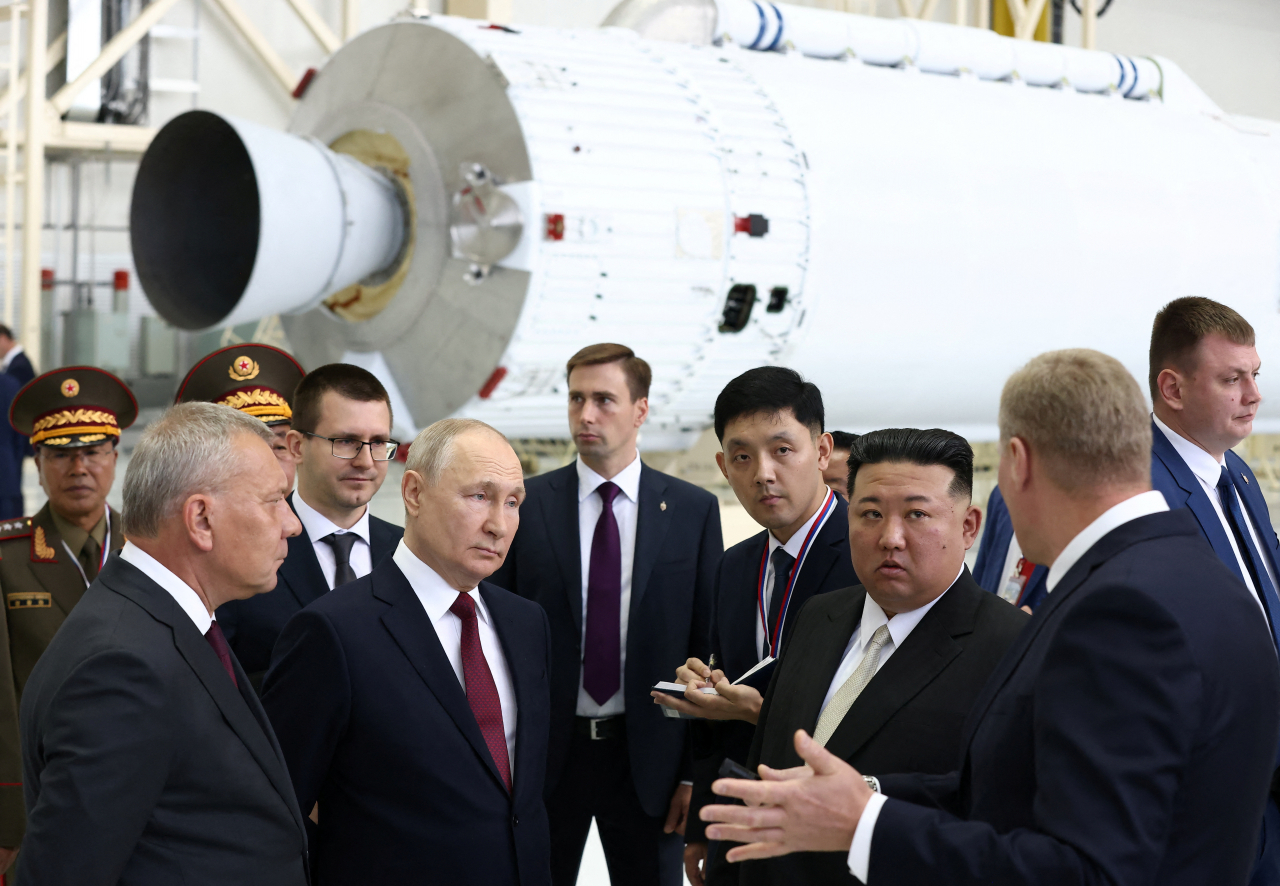

Russia's President Vladimir Putin (center left) and North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un (center right) visit the Vostochny Cosmodrome in the far eastern Amur region, Russia on Wednesday. (Reuters-Yonhap) |

Vostochny Cosmodrome, Russia's massive spaceport that is about 5,500 kilometers east of Moscow, drew international attention on Wednesday, as the leaders of two isolated countries, North Korea and Russia, met in a high-profile summit there.

The spaceport sprawls across 551.5 square kilometers of land -- outsizing South Korea's state-run Naro Space Center by over 100 times. It began operation as the main spaceport there in 2016, replacing Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, which had been the main launch site for the Soviet Union since the 1950s.

As the space center symbolizes Russia's ambitions to space exploration, President Vladimir Putin holding the summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un there raised the possibility of the two forging technology cooperation as well as an arms deal.

The summit was held at a time when North Korea is desperately looking for a breakthrough in weapons development, as the reclusive Kim regime is halfway through its five-year plan to achieve military goals for defense science and weapons systems.

"North Korea lags behind in the technology for military reconnaissance satellites and tactical submarines as it pursues its five-year military goals," said Lim Eul-chul, a professor at Kyungnam University’s Institute for Far Eastern Studies in Seoul.

"North Korea has long envisaged Russia's advanced technology in those fields, and the prolonged war between Russia and Ukraine allowed North Korea to leverage opportunities to make room (for negotiations with Russia)."

Photos revealed by North Korea's state-run Korean Central News Agency showed that among the North Korean delegation are Pak Thae-song, a key North Korean official dedicated to the development of a spy satellite, as well as Kim Myong-sik, who is responsible for tasks related to the development of a tactical nuclear-armed submarine.

This cadre, along with Putin's revelation of his plans to visit the mega spaceport earlier this week, raised speculations that cooperation between the two countries over space technology could be on the agenda of the summit.

The summit bodes well for Kim's ambition to obtain technology or information related to space projectiles. Putin told reporters Wednesday that Kim "showed great interest in space and in rocket engineering" and that North Korea is "trying to develop space," when asked whether Russia would be willing to assist North Korea with building a space satellite ahead of their talks.

North Korea earlier this year in May and August had attempted to send a space launch vehicle twice, but neither achieved orbit. This triggered condemnations and additional sanctions from South Korea, Japan and the United States. The three countries have viewed North Korea's failed launch as a violation of United Nations sanctions.

Nonetheless, immediately after the second failed attempt, North Korea's space authorities expressed their intention to fire a third space projectile in October.

|

A Soyuz-2.1b rocket booster with a Fregat upper stage and lunar landing spacecraft Luna-25 blasts off from a launch pad at the Vostochny Cosmodrome in the far eastern Amur region of Russia, Aug. 11. (Reuters-Yonhap) |

Despite the setting, experts said the technological support Russia gives North Korea for its satellite program is likely to be limited.

Neither the Soviet Union nor Russia have ever transferred any cutting-edge space technology to its allies, said Park Won-gon, a professor of North Korean studies at Ewha Womans University.

But Park added that North Korea's large stockpile of ammunition that is compatible with Russian weapons, such as 152-millimeter artillery shells, could still help the North get what it wants to overcome crises such as a food shortage.

"From North Korea's perspective, exchanging (its artillery ammunition) for food, energy resources and fertilizers could be practically important options," he said.

Lim of Kyungnam University said that now is unlikely the time for North Korea to seek shortsighted solutions to handle its satellite problems.

Kim's visit to the Vostochny Cosmodrome could "lay a cornerstone for institutionalized mid- to long-term cooperation between North Korea and Russia over space development," Lim said.

"Given the massive scale of the Vostochny Cosmodrome, Kim's visit to the spaceport site would still mean a lot to him."

North Korea has put two space satellites into orbit -- not necessarily for military purposes -- out of seven since the regime proclaimed the first launch of an artificial satellite in 1998. It sent Kwangmyongsong 3-2 into orbit in 2012 and Kwangmyongsong-4 in 2016.

The Kwangmyongsong-4 fell to the Earth in late June and is currently not in orbit, according to space satellite tracker N2YO. Also on Sunday, Marco Langbroek, an astronomer and lecturer of aerospace engineering at Delft Technical University in the Netherlands, forecast that the Kwangmyongsong 3-2 would reenter the Earth in "no more than a mere week" on X, formerly known as Twitter.

North Korea has yet to disclose any satellite images or records of transmissions from any of the two satellites.

This has often drawn speculations that North Korea has actually been conducting engine tests potentially powerful enough to launch an intercontinental ballistic missile that could reach as far as the United States, under the guise of space satellite launches.

In addition, South Korea, Japan and the US regarded the 2016 launch of Kwangmyongsong-4 as a missile launch because it was too light to be regarded as a functional space satellite. Technically, the rocket used to launch the space satellite can also be compatibly used to launch a missile.

As for the May launch of what North Korea claimed to be a space satellite on a carrier rocker Chollima-1, however, the South Korean Joint Chiefs of Staff has described the object retrieved from the Yellow Sea as "North Korea's proclaimed space projectile," despite evidence that Chollima projectiles were powered by the technology used to fire ICBMs, and that they adopted components that were used in the ICBMs.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)