|

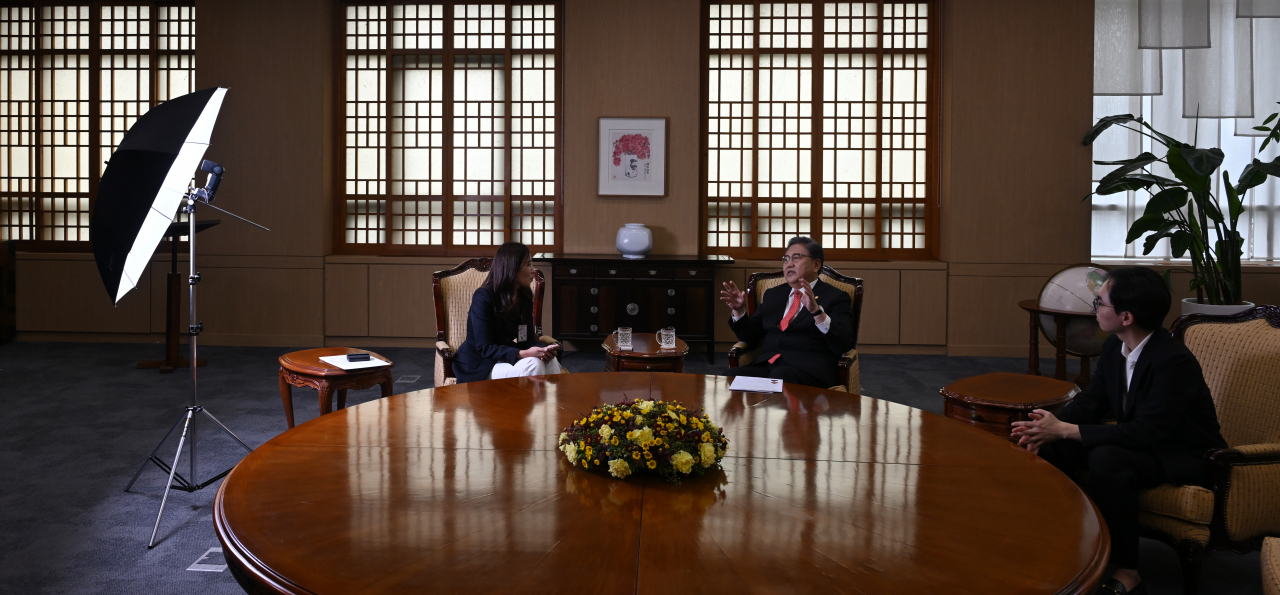

Foreign Minister Park Jin speaks during an interview with The Korea Herald at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Seoul, Sept. 25. (Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald) |

Long before he became foreign minister, Park Jin had set his sights in high school on practicing medicine, just like his father. That was, until a news article changed course for him.

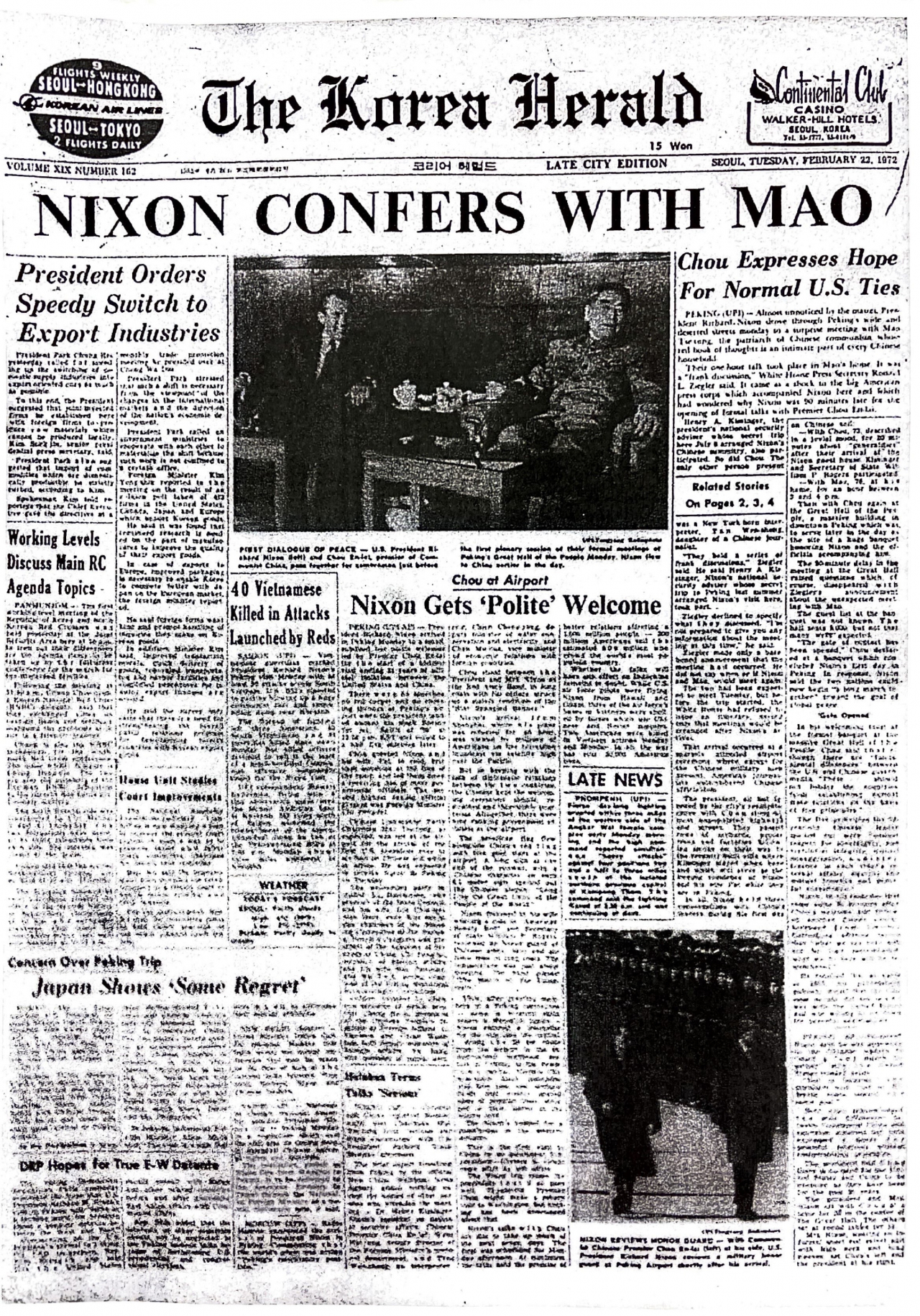

“So my father, who used to read English newspapers every day, handed me this report and the words he underlined were: the US-China detente,” the foreign minister said in a recent interview with The Korea Herald.

Park, 67, was referring to a Korea Herald article of former US President Richard Nixon’s visit to China, the first of its kind, in late February 1972.

The word “detente” changed everything, he said.

“I looked up detente. And I thought to myself: This is diplomacy, I mean ‘real diplomacy,’” Park added. At that moment, he decided to pursue just that. Nixon was impeached before ties could be fully established, but the tour eventually led to the start of full diplomatic relations in 1979, a watershed moment in world history.

Park had a taste of what it was like at diplomacy’s top table in April 1993, when he was former President Kim Young-sam’s young press secretary interpreting a discussion with Nixon. Park reached the top of his profession in May last year, when President Yoon Suk Yeol took office and named him foreign minister.

A four-term lawmaker who had previously chaired the National Assembly committee on foreign affairs and unification, Park is the chief architect behind Yoon’s Indo-Pacific strategy.

The plan, revealed in December, focuses on making South Korea a “global pivotal state,” one that looks after its own as well as global interests, while upholding the rules-based international order.

|

A copy of The Korea Herald’s front page on Feb. 22, 1972, on the US-China detente. South Korean Foreign Minister Park Jin described the report as what led him to pursue diplomacy as his career. (Korea Herald file photo via National Library) |

Looking beyond North Korea

The grand initiative, Park underscored, starts with South Korea increasing curbs on North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, with backing from countries like the US and Japan, and like-minded countries committed to following the rules-based international order.

“Korea’s journey toward freedom, peace, and prosperity would not have been possible in the absence of the rules-based international order,” Park said.

Washington’s military support has been instrumental in Seoul’s ascent, given their defense treaty inked to prevent another Korean War. Before that, the South’s chief ally helped push back the North’s forces in the 1950-53 conflict and reach an armistice.

“Korea is strengthening its alliance with the US and trilateral cooperation with the US and Japan,” Park said of a White House summit in April when Yoon met with US President Joe Biden, and a trilateral meeting in August, when Yoon sat down with Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

The April meeting led to a nuclear pact that gives Seoul a bigger say in how Washington handles its nuclear umbrella, a strategy the two allies call “extended deterrence” aimed at preventing a North Korean nuclear strike. The August summit ensures deeper trilateral ties to counter threats from the regime, such as missile launches, in their first-ever security pledge.

The “rapprochement with Japan” is another proof that Yoon’s Indo-Pacific policy “is working in reality,” Park noted. Many see the Korean leader’s March proposal to clear colonial disputes with Japan dating back to its 1910-45 occupation of the Korean Peninsula had contributed to bolstering the coalition on North Korea.

The March deal, which offers restitution to Korean laborers forced to work for Japanese companies during World War II through private donations, helped end a 12-year hiatus in May on “shuttle diplomacy” or leader-level visits the two neighbors consider essential to robust ties. Park described the measure as “building future-oriented relations.”

“We will continue to take a comprehensive approach of deterrence, dissuasion and diplomacy,” Park said of a three-pronged approach to Pyongyang, which defies not only United Nations sanctions on its nuclear weapons programs but outreach for dialogue. The approach would likely involve economic aid in return for disarmament. The North wants sanctions relief first, the reason talks have stalled.

Not cornering China, a key partner

The push for closer ties with the US and Japan while championing the rules-based international order appears to have worried China, a country that is looking to make changes to the “the US-led order.”

Critics argue that friction with China is unavoidable, but Park disputes that. He said Korea is cultivating a “sound and mature relationship,” an effort in progress as the two pursue “shared interests based on mutual respect and reciprocity.”

“Our Indo-Pacific Strategy makes it clear that China is a key partner for achieving peace and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region. Accordingly, we are promoting cooperation with China under the spirit of ‘harmonious coexistence while respecting differences,’” Park said.

Tensions between Seoul and Beijing flared earlier this year, when China’s top envoy in Korea publicly warned Seoul against betting on Beijing losing out to Washington.

“There is a steady flow of high-level talks between Korea and China,” Park added.

In early September, Yoon met with Chinese Premier Li Qiang on the sidelines of the ASEAN summit in Jakarta, Indonesia, a meeting followed by another later the same month between Prime Minister Han Duck-soo and Chinese leader Xi Jinping. Han was visiting Hangzhou, China, for the Asian Games.

Xi told Han he would seriously consider visiting Korea. A trip, which would be his first since 2014, could be a clear political win for the Yoon administration. Yoon’s national security adviser, Cho Tae-yong, has declined to elaborate on the timeline but has said a trip will happen in one way or another.

The visit is likely to follow a summit between Korea, China and Japan -- a get-together Seoul is planning to reopen this year as this year’s host. The COVID-19 pandemic and international tensions led to the suspension of the talks since the three sides last met in 2019.

“The resumption of the trilateral consultative mechanism will open up new opportunities for the three countries to cooperate even more closely and contribute to strengthening their respective bilateral relationships,” Park said.

|

Foreign Minister Park Jin poses for a photo ahead of an interview with The Korea Herald at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Seoul, Sept. 25. (Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald) |

Dealing with Russia

The latest headache for Foreign Ministry policymakers is the growing potential for Russia’s arms deals with North Korea, an exchange where Moscow restocks munitions to advance its grinding war in Ukraine while Pyongyang secures weapons technologies like satellites and submarines.

From Sept. 15-16, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un toured weapons plants in Russia’s eastern cities of Komsomolsk-on-Amur and Vladivostok, two days after his meeting with President Vladimir Putin, also in Russia’s Far East. The first summit between the two leaders in four years came as the two autocrats faced increasing global isolation.

“Military cooperation, especially arms trade, between Russia and North Korea is not only illegal but unjust,” Yoon said in a Sept. 19 speech at the UN General Assembly, describing such project as violating UN Security Council Resolutions and international sanctions.

The resolutions ban the North from making arms transfers and testing ballistic missile technology, which is used in satellite launches. The regime is eyeing a third spy satellite launch after two previous failures this year, having also unveiled what it says is a submarine capable of launching tactical nuclear weapons.

That fanned speculation that Pyongyang is serious about acquiring Moscow’s weapon know-how.

“The Republic of Korea government will not stand idly by in the face of such threats,” Park said, using South Korea’s official name. Any illegal arms trade is a global concern, Park added. “To this end, we will continue to impose autonomous sanctions on North Korea and strengthen our cooperation with the international community.”

For Park and his ministry, December is more than a month to round out the year, because the country will mark the first anniversary of the Indo-Pacific strategy, when the top diplomat says he could possibly roll out a “blueprint for effectively implementing” the initiative while also identifying related projects and partner countries.

“The international community is looking to countries like Korea to do more to step up to uphold the rules-based international order and help overcome the global crises,” Park said.

Who is Park Jin?

Park Jin began his diplomatic career at the Foreign Ministry in 1977, after passing the foreign service examination at the age of 20. After quitting the job the following year, he earned a master’s degree in public administration at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government in 1985 and a Ph.D. in politics at the University of Oxford in 1994. In between, he served as a politics lecturer at Newcastle University from 1990 to 1993.

From 1993-1998, he served as former President Kim Young-sam’s press and political affairs secretary, separately.

Park entered politics winning a by-election in 2002, representing the Jongno district at the Hannara Party or the Grand National Party -- a predecessor to the ruling People Power Party. He has since been with the conservative party, which underwent name changes. As a four-term lawmaker who chaired the foreign relations committee, he currently represents part of the Gangnam district.

Versed in international relations with a forte in handling North American and Commonwealth affairs, Park helped Yoon craft his foreign policy when he was president-elect. Like Yoon, Park is a Seoul National University law graduate.

|

Foreign Minister Park Jin (center) at an interview with The Korea Herald with Korea Herald reporters at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Seoul on Sept. 25, 2023. (Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald) |

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)