|

(Getty Images) |

The pressure to attend corporate evening gatherings has diminished in recent years, especially while social-distancing measures to contain COVID-19 were in place, but drinking remains a source of stress for many Korean workers.

As the year-end holiday season approaches, Lee Ha-seong, a 31-year-old Seoul-based economic news reporter, has a worry on his mind, saying that he doesn't drink well.

For Lee, the most challenging part of life as a journalist in Korea is not the reporting but the drinking that comes with it.

He believes that it is impossible to build the relationships he needs to do his job without drinking.

"Most social gatherings involve people drinking a lot until everyone loses their minds," he said.

Lee is one of many Koreans who complain that heavy drinking brings advantages when building relationships in workplaces and at other business occasions here.

But where does such belief come from? Experts point to Korean culture where alcohol has played various important roles throughout Korean history.

Literary works and historical archives tend to describe alcohol positively, as necessary for human health and life, according to the "Encyclopedia of Korean Culture," released by the Academy of Korean Studies. For instance, the sentences, “Alcohol is the best of a hundred medicines,” and, “Drinking alcohol gives muscle strength and relieves lingering illness,” comes from the ancient Chinese text, "Han Shu Shi-Huo zhi," written during the Goguryeo era (37 BC-668 AD).

Other literary works read that alcohol can serve as a means for people to socialize with family members and friends, fostering deeper conversations that strengthen personal relationships far more effectively than before they started to raise their glasses together.

"There is nothing better than alcohol to honor the elderly and perform ancestral rites," according to the "Seonghosaseol" (1723). And, "Alcohol is necessary to circulate one's 'qi' and blood, spread 'jeong' (affection) and perform rites," reads the "Chungjangkwan Jeonseo," written during the latter 18th century.

Some experts say that the present notion of drinking as a virtue comes from Confucianism, and that, as a result, alcohol-friendly ideas have permeated Korean culture.

Confucianism, a traditional belief system in East Asia, still holds significant influence in the Koreas, China and Japan.

In China today, people say that the amount of alcohol someone drinks reflects their sincerity to the person they toast, according to Lorna S. Wei, an assistant professor specializing in English linguistics at the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing, China. As a result, pouring alcohol for one another is a way of showing affection, she added.

The tradition of building social and business relationships over alcohol is also a longtime practice in Japan. The Japanese neologism, “aruhara," refers to being harassed to drink, often to excess, indicating negative sentiments toward coerced drinking.

Positive perceptions of heavy drinking, however, face more resistance today due to increased health awareness and growing emphasis on empowering individual rights, as well as the influence of social distancing measures and remote work culture during the pandemic.

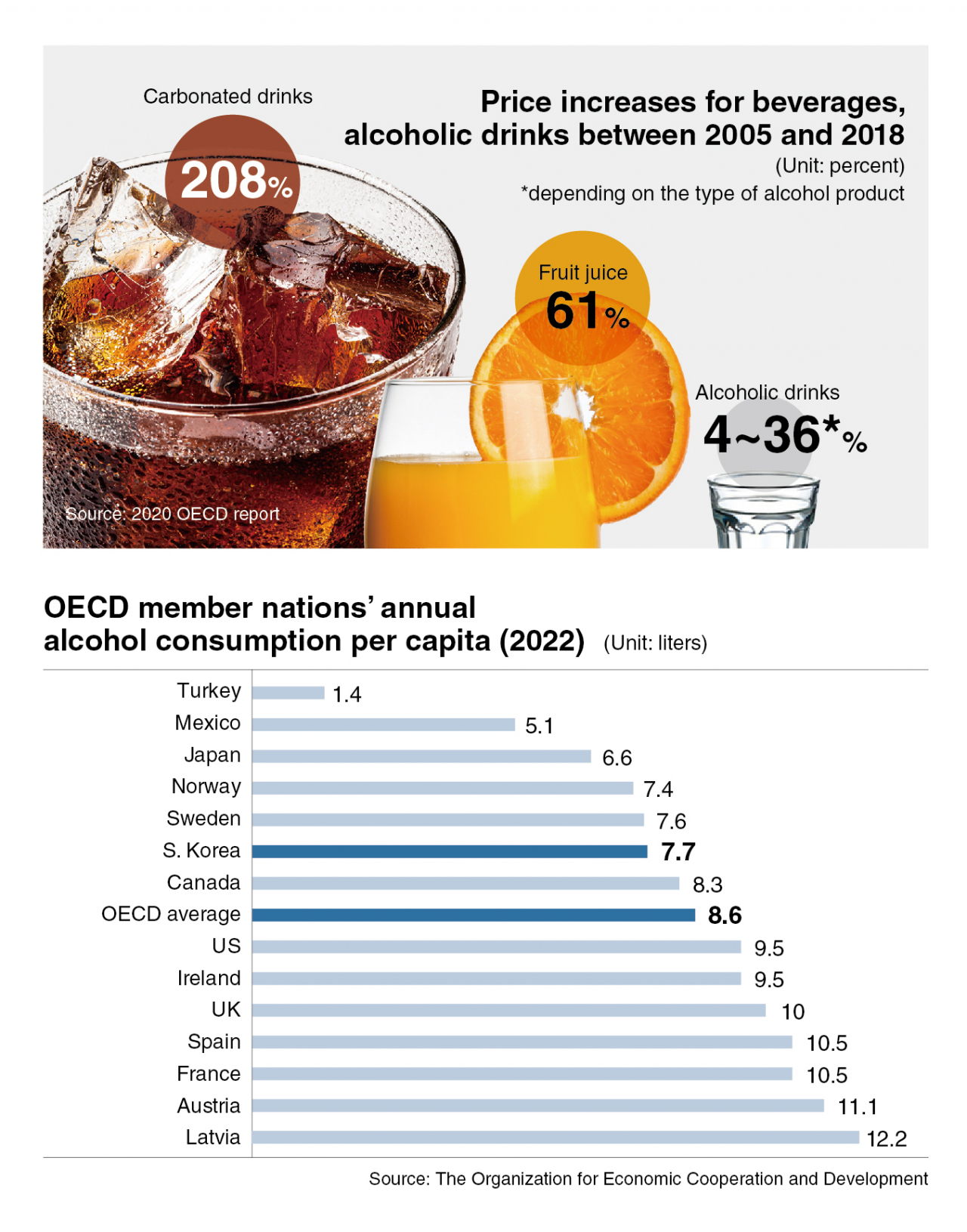

According to OECD data from 2022, Koreans in recent years actually don't drink as much per capita as the OECD average. Annual alcohol consumption per capita in South Korea recorded a rate of 7.7 liters last year, just under the OECD average of 8.6 liters in 2022.

However, the OECD's Health Statistics 2023 report noted regardless that Korea has a notoriously bad drinking problem, including a culture of binge-drinking and strong social pressure to participate in it.

Because one goal of company dinners called "hoesik" is for company subordinates and their superiors to get closer to each other, it is hard for even those who don't drink to refuse to attend them when asked by their bosses, managers or more senior employees.

In some organizations, skipping a hoesik is treated as a bigger sin than missing work.

According to job portal site JobKorea’s 2020 survey in which 659 workers were asked about their participation in hoesik, only 45 percent said they were "free to choose" whether to attend the company dinners, though 41 percent said they "worried how it would look" if they didn't. Thirteen percent said attendance was "mandatory."

Despite these statistics, even if originating from supposedly good intentions, one person asking another to drink can escalate into coercion in Korea, where subordinates worry that saying no to superiors could lead to exclusion, conflict or jeopardize their job itself.

This culture of seniors having the authority to ask subordinates to drink has resulted in some Koreans even losing their lives due to being pressured to drink excessively.

According to a 2016 survey conducted by the Korea Public Health Association, there were 22 deaths resulting from coerced drinking at local universities 2006-2016. Those who died were mainly first-year university students who couldn't refuse when more senior students asked them to drink.

Coerced drinking occurs most often in workplaces where hierarchical relationships are strongly emphasized.

“Some employees who were pressured to drink at hoesik have died after drinking alcohol in Korea,” said Kim Hyun-deok, an attorney at labor law firm Cheongryang.

“In 2018, a worker who couldn't drink well died when he lost consciousness after drinking at a two-day workshop, which was judged by the court to be an occupational accident, considering the worker’s position as a new employee at a workshop attended by the worker’s boss, because the worker had likely been pressured to drink.”

However, the Korean government has generally been passive in tackling the culture of binge-drinking, experts say.

“Because alcohol is an addictive substance, it is very easy to get addicted to or drink too much. However, due to Korean culture considering alcohol a positive thing, Korea has almost no policies to limit alcohol consumption other than regulating drunk driving or restricting underage drinking. This is why binge-drinking is so prevalent in Korea,” said Lee Hae-kook, professor of psychiatry at the Catholic University of Korea and chair of the Korean Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

The government’s soft view on alcohol intake as well as the culture of binge-drinking here have made South Korea home to more and more alcoholics, according to Lee. Alcohol-related socioeconomic costs -- such as diseases and accidents -- amount to more than 20 trillion won ($15.13 billion) a year, according to the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

A study with the English title, “Prevalence of the Major Mental Disorders among the Korean Elderly," conducted in 2011 by Seoul National University geriatric mental health researchers showed that the lifetime prevalence of alcohol addiction in Korea was reported to be 13.4 percent -- skewed heavily toward men at more than 29.2 percent, compared to women at 3.1 percent.

Lee's view is that alcohol's low cost and taxes are other factors that have contributed to making Korea home to increasingly more alcoholics.

According to 2020 OECD data, alcoholic beverages in Korea have experienced less price inflation than other non-alcoholic beverages. While prices for carbonated drinks and fruit juice increased by 208 percent and 61 percent, respectively, between 2005 and 2018, alcohol drinks increased between 4 percent and 36 percent.

|

A shopper chooses a bottle of soju at a hypermarket in Seoul on Tuesday. (Newsis) |

Soju is particularly inexpensive. According to the Korea Consumer Agency, the average price of a standard 360-milliliter bottle of soju in Korea is 1,380 won at hypermarkets and 1,950 won at convenience stores, as of Oct. 20. A standard bottle of soju contains about 60 ml of alcohol, equivalent to about 1.3 liters of beer.

Lee argued for the need to raise the prices of alcohol by hiking alcohol taxes. "We need to drastically raise the price of alcohol through tax increases to limit people's access to it."

Experts from 20 health and medical groups who participated in the Forum for a Society Free from the Harmful Effects of Drinking, hosted by the Ministry of Health and Welfare last year said that government campaigns to curb drinking are needed. They said that the annual budget for alcohol abuse prevention has remained almost unchanged over the past 15 years, at 1.4 billion won. In contrast, liquor companies spent approximately 300 billion won per year on advertising.

"A separate law and budget are needed for alcoholism. Measures at the national level are needed,” they said.

In addition to all those governmental policy measures, experts stress that there also needs to be more change in the attitude of Koreans toward the culture of excessive, coerced drinking.

“People should be aware that excessive drinking has various negative effects on one's health, and should stop trying to force others to drink,” an official from the Korea Public Health Association said.

Fortunately, the culture of excessive drinking as a required "virtue" faces mounting resistance today. People now view it acceptable to decline alcohol, the Korea Public Health Association added.

“Coercion has now become a social taboo, protected by the laws, such as Article 324 of the Criminal Act, and Article 37 of the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act. Additionally, there is a growing awareness of the importance of a healthy lifestyle and the adverse impacts of alcohol.”

This article is the first installment of a series of features, analyses and interviews delving into the intricacies of persistent negative practices in South Korea that now face a growing demand for change to ensure that individual lives are respected. -- Ed.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)