|

Dr. Lujain Al-Qodmani, the president of the World Medical Association (Courtesy of Dr. Lujain Al-Qodmani) |

The South Korean government’s decision to add 2,000 new spots in medical school admissions is not a solution to alleviate the immediate needs of medically underserved or specialty areas, according to Dr. Lujain Al-Qodmani, the president of the World Medical Association.

In an exclusive written interview with The Korea Herald, the WMA head said the government’s decision overlooked the complexities of medical education and health care delivery and risks unintended consequences.

Al-Qodmani noted that raising the quota by over 60 percent within a single year, barring thorough negotiations with key stakeholders, such as the Korean Medical Association, the country’s largest coalition of doctors’ groups with some 140,000 members, raised “red flags.”

“The WMA has expressed reservations regarding the government’s decision to substantially increase medical school enrollment quotas without clear evidence to justify such a move,” she said, adding that the organization’s rationale stems from concerns about the potential repercussions of the drastic policy shift.

While the Korean government believes that having more doctors will broaden the reach of medical services in non-metropolitan areas and salvage the staffing crisis in essential fields, the president said the scheme fails to tackle underlying systemic issues within the health care system.

“The plan alone is unlikely to effectively address medical deserts and shortages in essential medical fields such as pediatrics and surgery.”

The president also said that the planned hike may compound existing challenges, placing undue strain on the country’s insurance system.

Instead, she pointed out creating the right incentives and fostering a safe and dignified working environment for physicians as “essential steps” to encourage practitioners to work in vital disciplines and areas with medical staff shortages.

“Comprehensive medical workforce planning, including gender-equal measures, is crucial to ensure an adequate distribution of health care professionals across regions and specialties,” she explained.

Drawing from resources such as the World Health Organization’s Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030, for example, could provide insights and guidance for effective policy implementation and staffing problems, Al-Qodmani said.

“The Korean government should adopt a more collaborative and peaceful approach in addressing the concerns of physicians, who are advocating for improving the health care system,” she said.

Schools ‘not ready’

The WMA chief was in agreement with medical professors here that schools are not ready for the increase in the number of medical students. She singled out shortages of professors and a lack of resources for medical training as “critical issues” that affect future teaching provided to students.

Currently, the annual quota for new students stands at 3,058 and has been capped at this level since 2006. This was reduced from the previous quota of 3,507 to assuage doctors protesting the policy of separating the prescribing and dispensing of drugs at that time.

Despite fierce opposition, South Korea’s 40 medical schools have collectively requested an increase in the annual student quota by 3,401 starting in 2025. This figure is 70 percent higher than the planned increase of 2,000 students.

“With an influx of new students, the demand for qualified instructors will only intensify, potentially exacerbating existing shortages and compromising the student-teacher ratio,” she noted.

The president warned that this could lead to diminished mentorship and guidance that could hinder students’ ability to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge to become competent physicians.

According to the Health Ministry’s data released in November last year, there are 11,502 full-time faculty members at 40 medical schools nationwide, and the total number of students stands at 18,348 as of 2022. Each medical professor handles 1.6 students on average.

While the number seems ample, the medical circle claims that professors, who often hold concurrent positions as physicians in hospitals, are overstretched in trying to manage patient care, research and prepare for lectures.

“(The professors’) arguments regarding the strain on already limited resources and the challenges associated with providing adequate medical training are legitimate and raise valid concerns about the quality of medical education and services,” she said.

For example, the availability of cadavers used for anatomical study and dissection is central to medical training. However, not addressing the limited supply of cadavers takes a toll on the already-scarce resource, which impacts the competency and proficiency of future physicians, according to Al-Qodmani. This, in turn, affects the quality of health care services provided to patients, she added.

She echoed that students have the right to access “well-equipped education environments,” including robust clinical experiences. But the absence of them will be a detriment to hands-on learning opportunities, and undermine the depth of understanding students develop through anatomical study.

“Ensuring that each medical student receives comprehensive training and exposure to the latest scientific knowledge is pivotal for maintaining high standards of medical care.”

Right to strike

The Junior doctors’ walkout has entered its fourth week. Students are leaving classrooms, and medical professors are quitting in droves in a show of protest, which the Yoon Suk Yeol government sees as collective action that breaches medical law and holds people’s lives and health hostage.

|

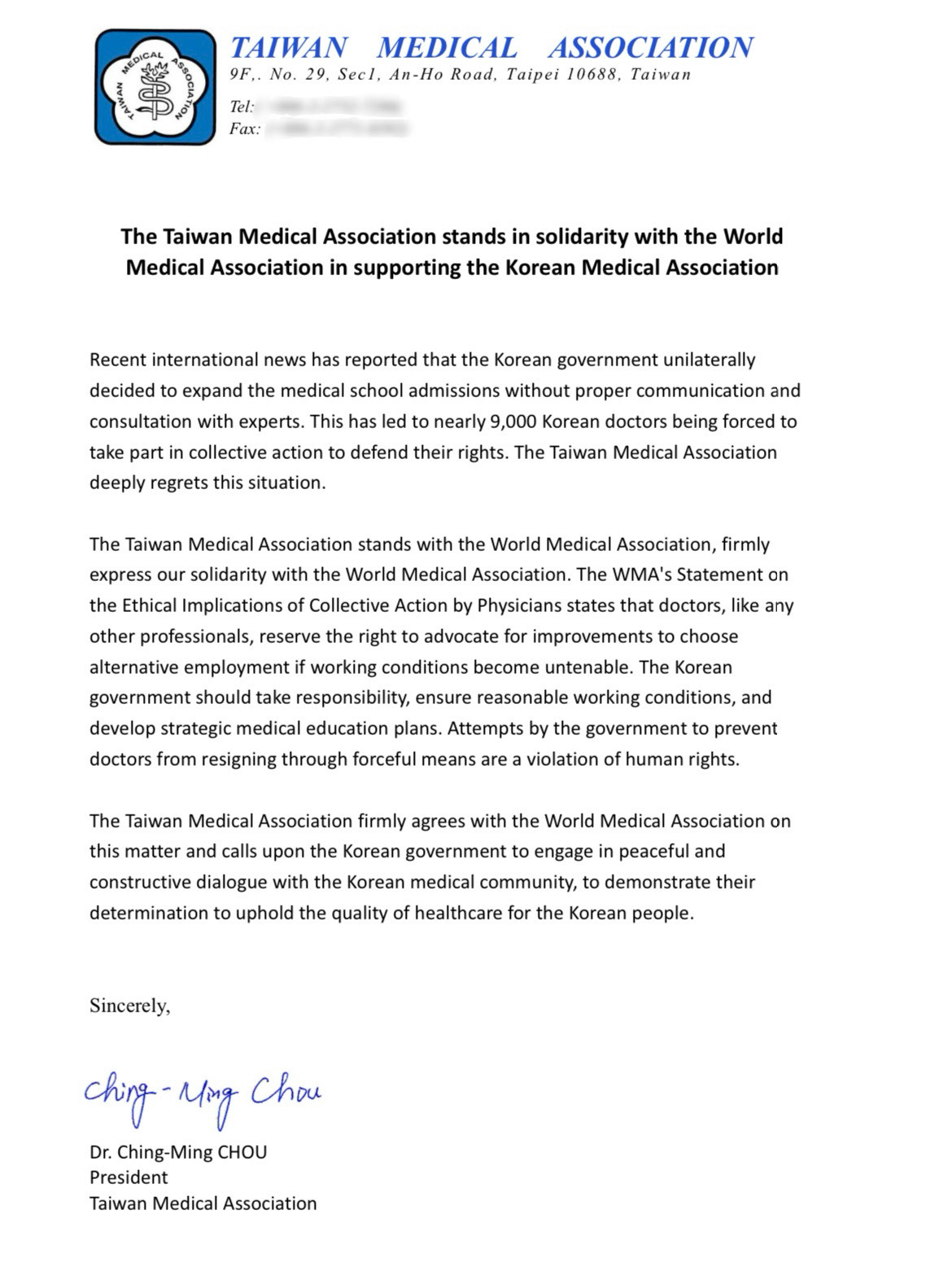

A license suspension notice sent to a junior doctor by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Courtesy of Ryu Ok Hada) |

As a consequence, authorities have started taking legal steps against trainee doctors who refused to heed return-to-work orders, such as by moving to suspend their licenses for at least three months. Police have also opened investigations against five former and incumbent KMA executives for allegedly aiding and abetting junior doctors’ collective resignations. Public sentiment has not been supportive of the doctors’ actions, with some criticizing them for allegedly abandoning their Hippocratic oath.

The WMA president, however, described these as “independent decisions” to leave their schools and workplaces. She underscored that such actions are “driven by personal beliefs and reasons” rather than external instigation or recommendations from organizations like the KMA.

“Physicians, including interns and residents, have the fundamental right to engage in collective action. From my perspective, the actions of the Korean medical community align with this guidance and are not in conflict with ethical standards,” she said.

She added that the attempts to prevent personal resignations and impose restrictions on school admission conditions set a “concerning precedent in the country.” The WMA also views the situation as a potential violation of human rights, she said, adding that doctors were peacefully practicing their rights without physically violating the law or Constitution.

“It’s rare to witness governments resorting to such drastic measures in response to collective actions by physicians. ... Doctors have the fundamental right to engage in such, such as strikes, as protected by constitutional rights. This right is also underscored in our statement on the ethical implications of collective action by physicians.”

Amid the continued standoff, she said the WMA will continue to support Korean doctors, adding that the KMA has officially requested support from the WMA.

The WMA, established in 1947, is the largest medical organization, representing 116 national medical associations around the world.

“WMA stands firm in support of the KMA, a prestigious member of the WMA, advocating for their rights and well-being during this challenging period.”

On Thursday, the Taiwan Medical Association also issued a statement that it stands in solidarity with the WMA in supporting Korean doctors, becoming the first international group to openly declare support for the KMA.

|

The Taiwan Medical Association issued a statement late Thursday that it stands in solidarity with the World Medical Association in supporting the Korean Medical Association. (Courtesy of the Korean Medical Association) |

When asked what next step should be taken by the government, Al-Qodmani said it should engage in meaningful dialogue with stakeholders like the KMA to identify mutually acceptable solutions.

“The dialogue should prioritize the concerns raised by physicians regarding the proposed expansion plan,” she noted.

“Without such collaboration, tensions will persist, violating the rights of physicians and potentially adversely affecting both the health care system and the well-being of the Korean population.”

Al-Qodmani, a global health and medical professional, is the WMA president for the 2023-2024 term. She earned her medical degree from Kuwait University and a Master’s in international health care management, economics and policy from SDA Bocconi.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)