|

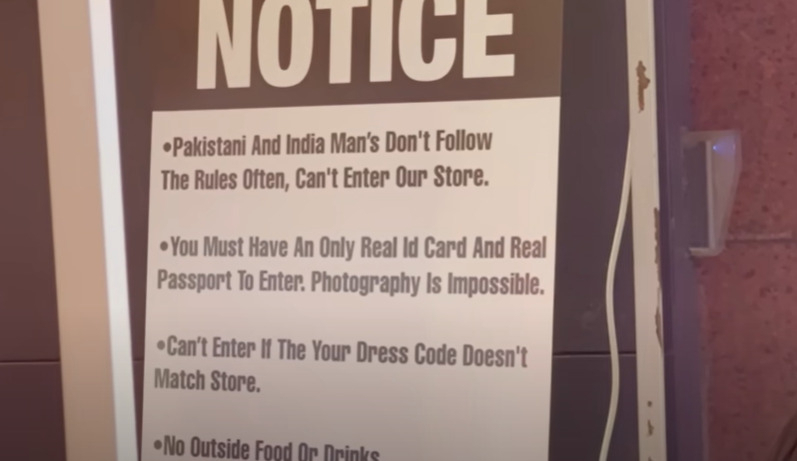

A sign hanging at the entrance of a club in Seomyeon, Busan. (YouTube) |

Raj, an Indian resident of South Korea for nine years, was shocked during a visit to Busan when a club bouncer bluntly informed him and his friends, "You cannot enter because you are Indian." Despite their objections, they were directed to a neighboring club, only to encounter a notice explicitly barring entry to Indian and Pakistani men.

The incident gained widespread attention after Raj's video of the discriminatory notice went viral, courtesy of Indian YouTuber Nikita Thakur, whose re-upload of the footage sparked discussions among viewers about the prevalence of such discrimination in Korea.

Being denied entry into a club because of nationality or skin color is not something new in South Korea. In 2017, an Indian student studying in Korea recounted a similar experience to local media, where he was refused entry to a club in Itaewon while his peers from other countries were allowed in. The club allegedly had a policy banning individuals from certain countries, including India and Pakistan.

The general perception among Koreans is that Korea is not a racist country, as incidences of physical violence toward foreigners are relatively rare. However, the aforementioned incidents suggest that racial discrimination persists in parts of Korean society.

According to a 2023 report by US News & World Report, South Korea ranks ninth out of 79 countries in the world in terms of racism.

A 2020 survey conducted by Segye Ilbo also showed that 69.1 percent of 207 foreign nationals residing in Korea had experienced discrimination or been subject to hate-based attacks. While direct physical assaults accounted for only 3.4 percent of all cases, instances of indirect discrimination, such as gestures or hostile eye contact, comprised 32.9 percent. Moreover, 16.4 percent reported being the recipient of personal insults, including verbal abuse, while 10.6 percent cited unfair treatment, such as wage discrimination.

Racial discrimination in Korea occurs depending on whether the foreign national's country of origin is a developed country, according to the National Human Rights Commission of Korea. In other words, discrimination occurs depending on the economic status of the country of origin. For example, Koreans are more likely to discriminate against Black people from developing countries than Black people from the US, an official from the NHRCK noted.

A 2019 report by the NHRCK showed that 56.8 percent of the 310 immigrant respondents answered that Koreans discriminate based on “country of origin.” Also, 36.9 percent said Koreans discriminate based on their “economic level.”

“The way Koreans treat foreigners varies dramatically depending on whether they come from a developed country or not. Koreans tend to perceive foreigners first by their skin color, and then by their country of origin,” an official from the NHRCK explained.

Another NHRCK report showed that immigrants and foreigners feel discrimination even from public institutions.

In the same 2019 survey by the NHRCK, foreign nationals pointed to immigration offices and courts as locations where they experienced the highest levels of discriminatory treatment. Out of those surveyed, 41 percent reported encountering discrimination in courts, while 35.2 percent experienced similar treatment at immigration offices.

Some Koreans recognize this discrimination against immigrants as a problem, too. According to the NHRCK's 2022 Human Rights Awareness Survey of 16,148 Koreans, only 41 percent of Koreans said that the human rights of immigrants living in Korea are guaranteed equally to those of Koreans.

Protests from foreigners

Ahead of the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination on Thursday, Regina, head of the Yongin Filipino Community, said, “Even when seasonal workers report unfair treatment, such as unpaid wages or having their passports taken away, to the police stations or government offices, public officials try to solve the problems by siding with Korean business owners or Korean brokers rather than helping the foreign workers.”

Immigrants and foreign workers point out that there is already a large number of foreigners residing in Korea, and that Korea is no longer a country that can function properly without the labor of foreigners. Therefore, they say, the Korean government must make efforts to not discriminate against them.

“The number of immigrants in Korea has reached nearly 2.5 million, or 5 percent of the total population, as of January. The Korean government and business owners brought in migrant workers because they needed them, and they are working in various industries such as manufacturing, agriculture, fishing, construction and services. Many industries in Korea are now unable to sustain themselves without migrant workers,” Udaya Rai, head of the Migrants Trade Union, said Sunday during a protest outside Seoul Station.

He stressed that the nation should put in effort to protect them and that the nation lacks a comprehensive law addressing all forms of discrimination, compounding the challenges faced by marginalized communities.

Like him, human rights activists and immigration policy experts emphasize the prevailing social inequality, including racism, faced by minorities in Korea, highlighting the absence of legal protections. Alongside Japan, Korea is the only country among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development member nations without such a law. Since 2007, anti-discrimination bills have been proposed more than a dozen times at the National Assembly, but none have passed the final stage, mainly due to backlash from conservative religious groups who took issue with protections for sexual minorities.

“In Korean society, conservative Protestant groups are at the forefront of opposition to the legislation largely because homosexuality goes against their religious beliefs,” said Jang Ye-jeong, an activist from the South Korean Coalition for Anti-discrimination Legislation.

For example, there are currently four anti-discrimination bills pending in the National Assembly. The main opposition Democratic Party of Korea's policy committee tried to discuss the anti-discrimination bill as a major issue in June last year, however, the discussion was reportedly blocked by Rep. Kim Hoi-jae, a Protestant Christian.

“Also, lawmakers seem to feel less of a need to enact anti-discrimination legislation because they are not the ones being discriminated against, but rather vested members of Korean society. However, on the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, I once again emphasize that an anti-discrimination bill must now be passed.” Jang added.

“To turn this homogeneous society into an open community for immigrants, there must first be a law that guarantees them protection from racial discrimination. As Korea moves to open up more on immigration, the anti-discrimination law is a must,” Yoon In-jin, a sociology professor at Korea University told The Korea Herald.

Foreigners experiencing discrimination have been filing complaints to the National Human Rights Commission of Korea. For businesses placing a sign that foreigners are not allowed, the human rights watchdog has been issuing its recommendation that such practices of restricting entry based on race and skin color are unacceptable. But such a recommendation is not legally binding.

“In order to abolish racial discrimination, it is most important to enact legal systems such as anti-discrimination laws and it is necessary to expand exchanges between Korean indigenous people and immigrants and to create cultural diversity and human rights guidelines in the mass media,” the NHRCK report said.

|

Foreign workers hold a protest outside Seoul Station, in central Seoul, Sunday, demanding better treatment and legal protection against discrimination for non-Korean laborers. (Lee Jaeeun/ The Korea Herald) |

This is the fifth installment of a series of features, analyses and interviews exploring the challenges faced by Koreans and foreigners in creating a more diverse society in a South Korea rapidly shifting away from its homogeneous past. – Ed.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)