|

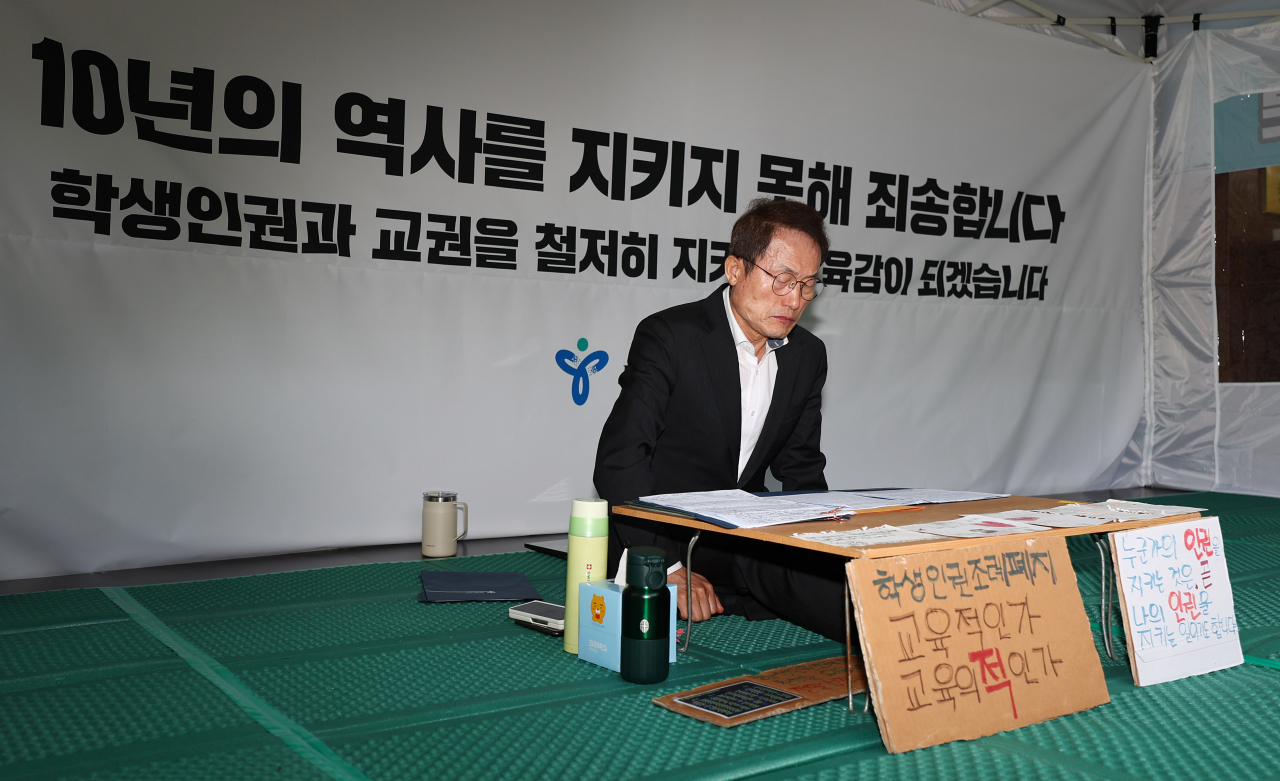

Cho Hee-yeon, Superintendent of the Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education continues a sit-in protest to oppose the abolition of the student rights ordinance in front of the education office in Seoul, Monday. (Yonhap) |

The debate over Seoul Metropolitan Government's abolition of its student human rights ordinance is set to expand to the National Assembly as the opposition Democratic Party of Korea plans to draft student rights legislation that would take precedence over regional offices’ decisions.

The Democratic Party, which holds a parliamentary majority, on Monday criticized the People Power Party's removal of Seoul's student rights ordinance, calling it "political regression" and an "anachronism" that "puts a nail in the coffin of human rights."

The city council abolished the student rights ordinance Friday, 12 years after it was adopted.

Councilors belonging to the main opposition Democratic Party of Korea boycotted the vote in protest, as the city council is dominated by the ruling conservative People Power Party.

"The Student Rights Ordinance lacks a firm legal foundation, so it suffers from being abolished in various situations, such as the change of political inclination of the superintendent, the composition of local councils, and the activities of organizations opposing the ordinance," the Democratic Party lawmakers said, calling for a unified legal framework.

"The new student rights act will take into account the concerns of teachers and provide exemption provisions for proper teaching guidance and daily educational activities of teachers," Rep. Park Ju-min of the Democratic Party said.

Pledging to supplement the legislation, the main opposition leader Lee Jae-myung urged the government to "endeavor to create an educational environment where teachers can focus on teaching children." He also emphasized that "school, especially the human rights of students should not be sacrificed for political gain."

Once the 21st National Assembly fails to propose the law, the opposition party could discuss school rights bills, which include the rights of both students and teachers in the 22nd National Assembly when it opens, according to Park.

Superintendent Cho Hee-yeon of the Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education also held a sit-in protest since Friday to oppose the council's decision to remove the ordinance.

At a press briefing held in front of the Seoul education office Monday, Cho said the legal deadline for the Seoul Metropolitan Council's reconsideration is May 17, adding that he would appeal for reconsideration of the removal.

However, as the bill abolishing the rights ordinance was passed with 60 votes in favor out of the 60 members present, the move is unlikely to be reversed. The education head can bring the case to the Supreme Court and request for a suspension of execution, according to the official.

The ordinance, first adopted in 2011 for schools in Gyeonggi Province and in 2012 in Seoul by progressive education superintendents, was introduced to promote student welfare by prohibiting corporal punishment and discrimination by teachers based on a student's gender, religion, age, sexual orientation or academic performance. It also allowed protests on school grounds, as well as giving students the freedom to choose their hairstyle and clothing.

Despite its noble intentions, the ordinance has faced criticism for damaging the welfare of the teachers.

Opposition to the ordinance was first raised by religious groups and parents who opposed its clause on granting freedom regarding sexual orientation, claiming that "the ordinance justifies unethical sexual conduct such as homosexuality, sexual transition, early sexual conduct and abolition.”

The criticism intensified after an apparent suicide by a 24-year-old elementary school teacher in Seoul’s Seocho-gu last July after suffering from constant harassment from parents.

Teaming up with the People Power Party politicians, teachers argued that the ordinance infringes on teachers’ and other students’ rights to education, leading President Yoon Suk Yeol to say the ordinance should be scrapped and replaced with guidelines that protect teachers' rights and enhance their authority.

Superintendent Cho, however, claimed that "The lawmakers of the People Power Party are splitting students and teachers, as students' rights and protection of teachers authority were incompatible."

"The fall of teachers' authority today is a complex problem resulting from excessive competition, commoditization of education, and changes in the social environment," he added. He also criticized the leading lawmakers' avoidance of fixing the fundamental problem, as the ordinance could be supplemented if necessary to protect the educational activities of teachers.

The Seoul education office had planned to legislate an amendment to the previous ordinance, in which both the responsibilities and rights of students are highlighted, while also respecting teachers’ rights.

After the South Chungcheong and Seoul education offices abolished the ordinance, there were six regional education offices — Gyeonggi, Gwangju, North Jeolla Province, South Chungcheong Province, Incheon and Jeju — that still enforce the ordinance.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)