|

President Yoon Suk Yeol bows to the public to wrap up his televised address to the nation in his office in Seoul on Saturday. (Presidential office) |

South Korea is facing unprecedented political turmoil as the ruling People Power Party, led by its chair Han Dong-hoon, grapples with the exit strategy that would otherwise determine the fate of President Yoon Suk Yeol.

Amid the opposition Democratic Party of Korea's persistent push for Yoon's impeachment following allegations of insurrection, the conservative ruling bloc has now strategically shifted toward calls for Yoon's “orderly resignation,” arguing that this path would ensure a more stable and orderly transition for the country.

Following Yoon’s announcement Saturday that he would let the ruling party manage state affairs, and the subsequent failure of the impeachment motion, the ruling bloc announced plans to sideline Yoon from state affairs, including foreign affairs. Announcing their intent in a joint statement by the ruling party chair and Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, Sunday, they did not specify what they meant by “orderly resignation.”

There are also interpretations that Yoon's remarks and the ruling bloc's promises should be deemed invalid under the presidential system set out in the Constitution in 1987.

In South Korea, a prime minister serves as acting president if a president is suspended or removed.

Sunday's joint statement fails to indicate the specifics about the relationship between the chief of the ruling party and the prime minister, not to mention the legal grounds on which the prime minister would replace the role of a legally sitting president.

|

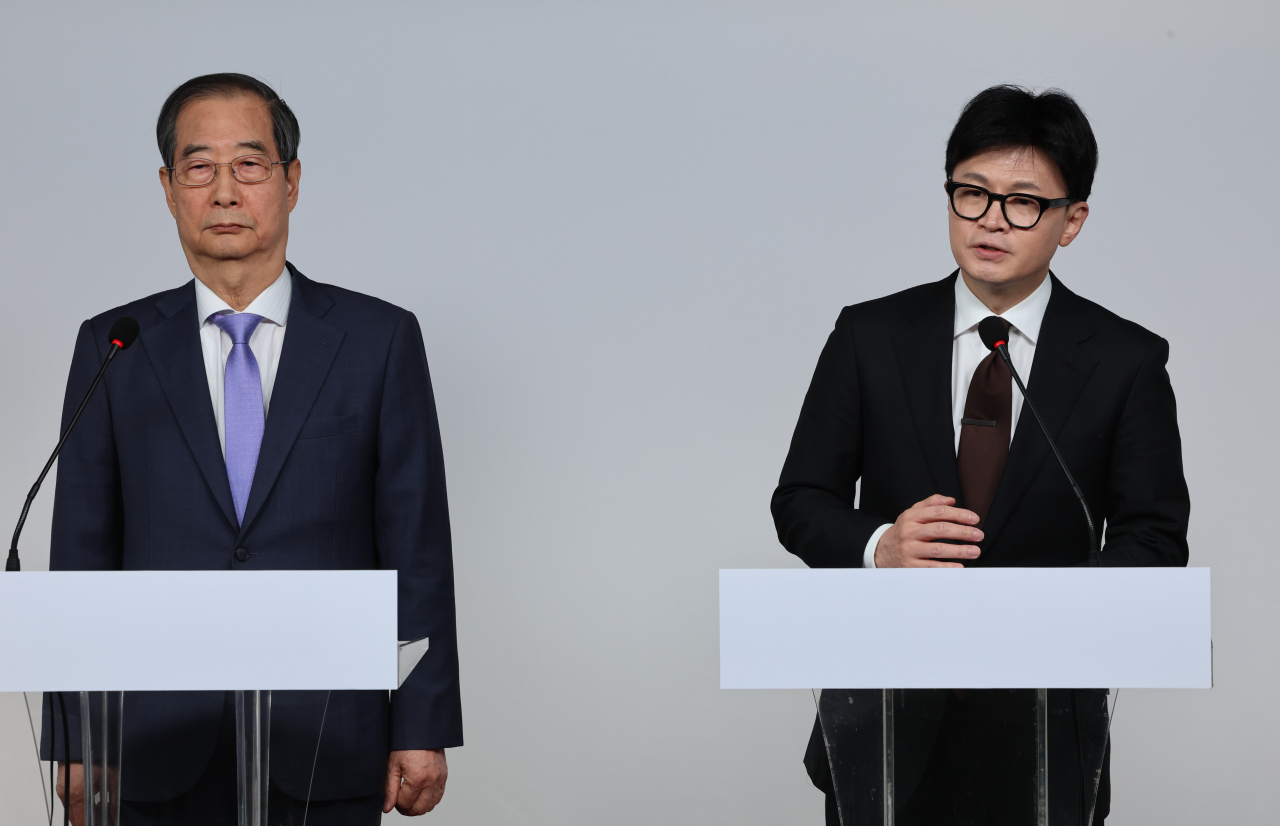

Prime Minister Han Duck-soo (left) and ruling People Power Party leader Han Dong-hoon deliver a joint public address at the PPP headquarters in Seoul on Sunday, one day after the parliamentary vote to impeach President Yoon Suk Yeol for his martial law imposition failed. (Yonhap) |

Under the Constitution, a South Korean president is the commander-in-chief of the nation's armed forces, represents the nation vis-a-vis foreign states and has the power to appoint leaders of institutions enshrined in the Constitution.

Under clause 84 of the Constitution, the president cannot be charged with a criminal offense during his tenure of office except for insurrection or treason.

With such protection of the Constitution, or without any binding changes to the Constitution, Yoon may take his power back from the party whenever he wants, an expert said.

"The president can take the lead again anytime he changes his mind," Shin Yul, professor of political science at Myongji University, told the Korea Herald.

"No one will be able to stop him, if Yoon insists."

National Assembly Speaker Woo Won-shik stepped in later Sunday, calling the sharing of a president’s authority between the party leader and the prime minister was a "clear violation of the Constitution."

"Authority does not lie inside a president’s pocket, nor can the transference of such power arbitrarily be decided by the president. … The handover of a president’s authority comes from the people, and the process must follow the Constitution and the principle of the people’s sovereignty."

|

Democratic Party of Korea lawmakers look solemn and disappointed as they watch ruling People Power Party lawmakers leave the National Assembly chamber before the parliament proceeds with the vote on the impeachment motion against President Yoon Suk Yeol on Saturday. (Yonhap) |

For Yoon to step down as president, legally, there are thought to be three options.

The obvious option is the impeachment, which in South Korea is a highly formalized process that begins with the National Assembly passing a motion by a two-thirds majority.

The case is then sent to the Constitutional Court, which determines whether the president violated the law or the Constitution. If upheld, impeachment results in the immediate and permanent removal of the president from office.

Former President Park Geun-hye, who was impeached in 2017 on charges of corruption and abuse of power, lost a range of privileges reserved for former leaders. These include the presidential pension, lifetime medical benefits, and logistical support. Additionally, any potential for political rehabilitation becomes almost impossible, as impeachment embeds a permanent stain on their record.

Impeachment also affects the president’s political allies and their party. The disgrace attached to the process can alienate voters, fracture the support base and lead the party into political decline, as evidenced by the fallout faced by the conservative bloc after Park's impeachment, which paved the way for the opposition's Moon Jae-in to rise to power in snap elections.

The second option would be a resignation, which occurs when the president steps down voluntarily before their term officially ends.

A resignation would preserve some of the president’s dignity, making it easier for them to remain a prominent public figure. While resignation may come amid significant political or public pressure, it is not formally accompanied by the stigma of unconstitutional or illegal behavior.

Under the Former Presidents Act, a president stepping down voluntarily can continue receiving their presidential pension, which amounts to 70 percent of their annual salary, along with lifetime medical coverage for both them and their spouse. They also retain access to personal security and logistical support.

The third theoretical option for suspending Yoon’s duties is petitioning the Constitutional Court to take action. However, this approach has failed in the past.

For instance, in 2016, a Korean civic group called the Citizens' Coalition for Economic Justice submitted an injunction to the Constitutional Court requesting the immediate suspension of Park’s powers.

The court, however, did not issue any ruling, leaving the matter unresolved. It was not until Dec. 9, 2016, when the National Assembly passed a motion to impeach her, which ultimately led to Park's removal from office.

|

Democratic Party of Korea Chair Lee Jae-myung arrives at the Seoul Central District Court on Nov. 25 in Seocho-gu, Seoul to hear the court verdict in his trial involving charges of subornation of perjury. (Yonhap) |

The ruling party appears to be aiming to maintain the current state affairs until at least one of the cases against opposition leader Rep. Lee Jae-myung results in a final decision at the top court that would bar him from running for president.

In November, Lee received a suspended one-year prison term for making false statements as a candidate during the previous presidential election. Lee will lose his parliamentary seat if a fine exceeding 1 million won ($702) is confirmed by the top court in this case. Additionally, his eligibility to run for office will be revoked for the next five years, barring him from participating in the next presidential election.

Moreover, the opposition leader is facing trials in multiple cases, including his alleged involvement in a North Korean remittance and a bribery case linked to land development scandals in Seongnam.