|

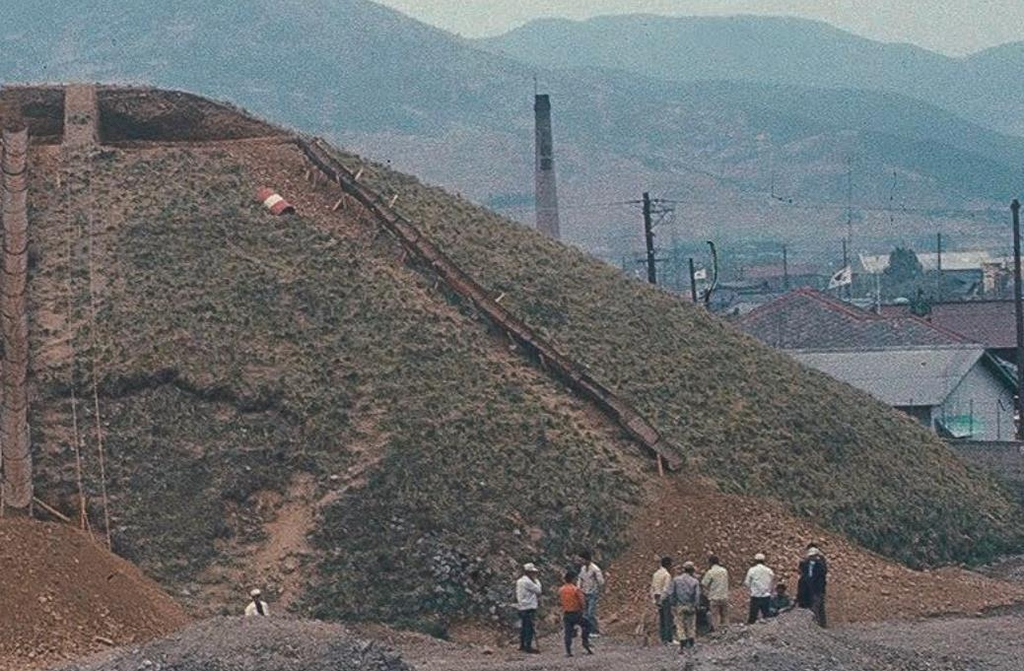

Field researchers, including Choi Byung-hyun (third from left) and So Seong-ok (third from right) examine Cheonmado at the excavation site of Cheonmachong in 1973. (Gyeongju National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage) |

This year commemorates the 50th anniversary of the excavation of Cheonmachong, an ancient royal tomb from the Silla Kingdom located at the Daereungwon Tomb Complex in Gyeongju, North Gyeongsang Province.

The tomb, from which more than 11,000 artifacts, including numerous treasures, were unearthed, tells a story of the ancient burial customs of the Silla Kingdom.

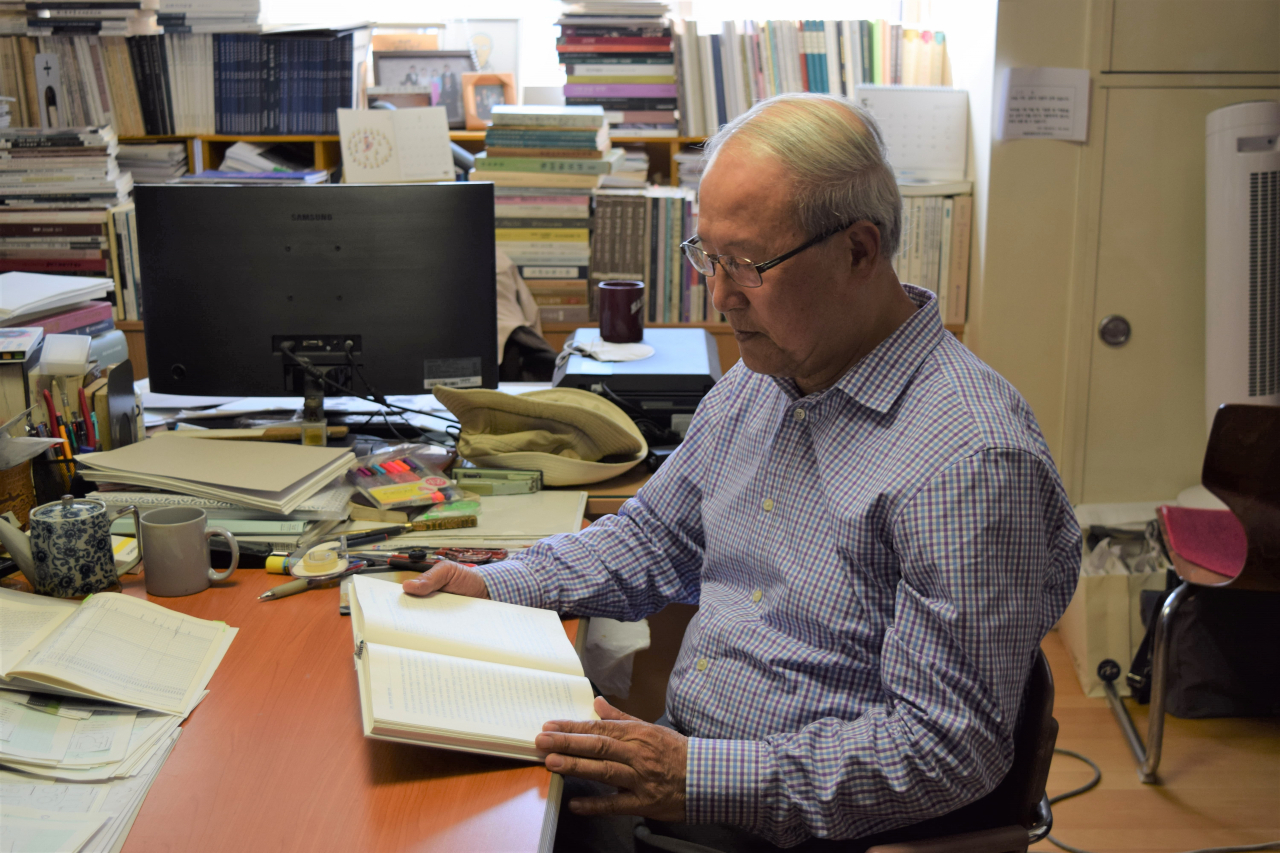

One of the seven field researchers behind the Cheonmachong excavation in 1973 was Choi Byung-hyun, a professor emeritus of history at Soongsil University and a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

Choi was in his mid-20s at the time and had just graduated college. Choi was recommended to the field research team by his professor. The other six members of the team were also recommended in a similar fashion, each by teachers from their respective schools.

"The daily wage offered for the Gyeongju excavation project was 1,220 won ($0.93), which was a significantly high pay for a college graduate at the time," Choi said during an interview with The Korea Herald on May 8. "Getting a job was challenging in the early 1970s, so there was no reason for a student to turn down such a great opportunity."

The team was led by the late Kim Jeong-gi (1930~2015), the top field excavation expert in the country. The government's initial order was to excavate Tomb No. 155, which later came to be called the Hwangnam Daechong Tomb.

Kim, who had worked as a section chief at the National Museum of Korea's archaeological department, after examination, concluded that Tomb No. 155 was too massive and that there would be difficulties figuring out the inner structure. This meant that the tomb itself could also be damaged during the excavation process.

"Kim was the head of the heritage department in the Culture Ministry and he persuaded President Park Chung-hee via the minister that the team work on Tomb No. 98 (Cheonmachong Tomb) first, as sort of a preliminary excavation research project before digging up No. 155." Choi said.

|

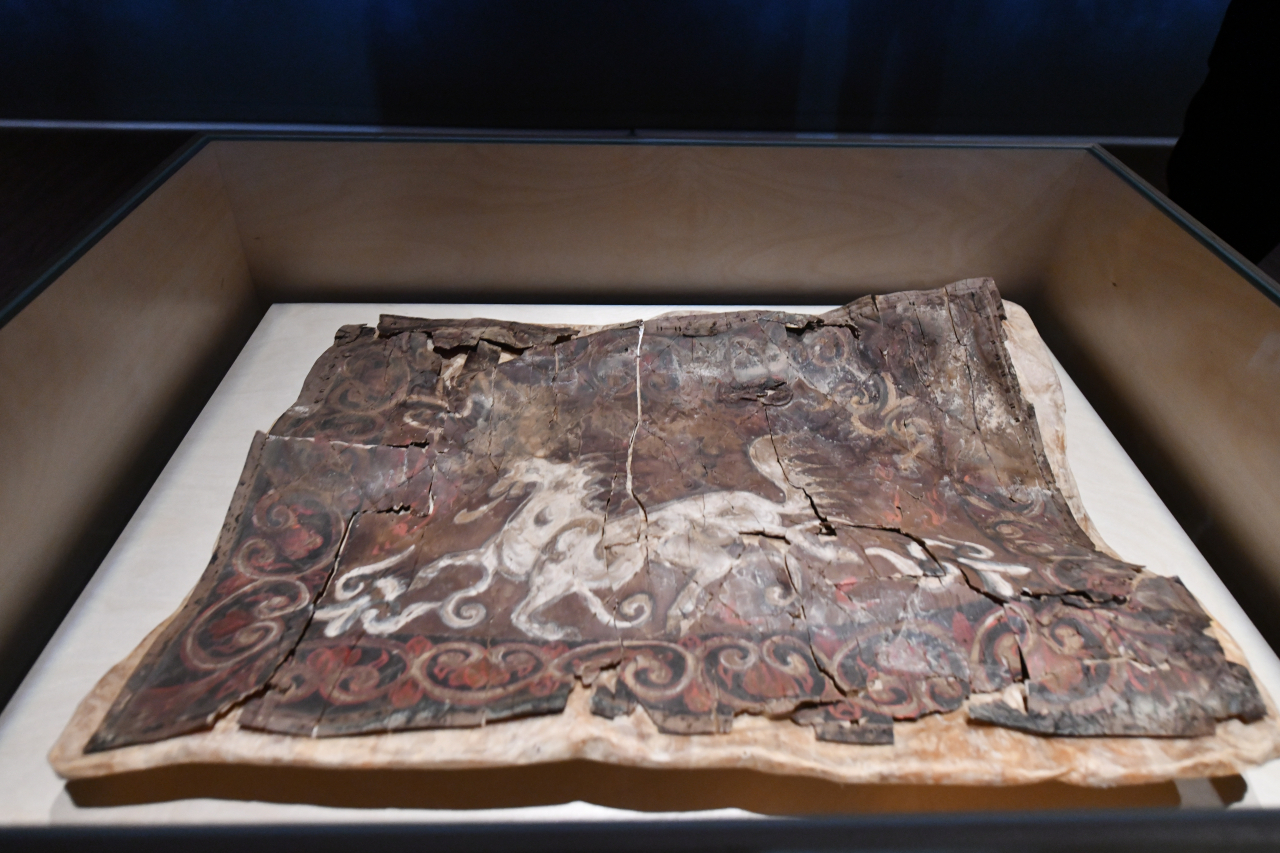

The "Jangni Cheonmado" is on display in the Gyeongju National Museum's special exhibition, "Return of Cheonma." (CHA) |

|

Choi at his office in Anyang, Gyeonggi Province, May 8. (Kim Hae-yeon/ The Korea Herald) |

Choi clearly remembered the moment Cheonmado -- the painting of a heavenly horse in Korean folklore -- was discovered in August of 1973. Drawn on "jangni," a mudguard flap made of birch bark that hangs down from a horse saddle, it seemed the piece was just about to fall apart and disintegrate into pieces at the slightest touch, according to Choi.

"Our leader (Kim) is the most patient person I have ever met in life. He always stayed calm and never panicked, even at the most critical moments. Even when the gold crown was unearthed, he didn't seem surprised at all." The gold crown had been discovered a month earlier, in July, at the same tomb.

But when Kim encountered Cheonmado, his face tightened and he began to tremble, according to Choi. It was evident to all on the site that he was deeply anxious. "He carefully observed Cheonmado, let out a sigh, and kept repeating to himself, 'This shouldn't have come out now.'"

Choi did not understand what Kim's words meant, since he was still a novice, having taken part in only two other excavations while in college. But it did not take long for him to realize the implication of the discovery.

"Back then, Korea's knowledge and expertise in artifact preservation studies was inadequate. While we were capable of handling basic metal parts and ceramics, we lacked even the fundamental understanding of preserving wooden artifacts. This was Kim's primary concern -- that it was not the ideal moment to encounter such a piece, as we were ill-prepared to provide the care it required.”

But as Choi recalls, the Cheonmachong was a wake-up call for the government. Shortly after the excavation, researchers were sent abroad for training in preservation, including to Japan and Italy. Cheonmado was designated as National Treasure No. 207 in 1982.

"Today, artifact preservation skills in Korea have reached an unprecedented level. We are now hosting researchers from Southeast and Central Asia, as well as going overseas to assist them uncover relics in their countries."

|

The research team prepares for the excavation of Cheonmachong in Gyeongju, North Gyeongsang Province, in 1973. (Gyeongju National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage) |

|

Choi Byung-hyun (left) works on the unearthed Cheonmado, which was drawn on a mudguard flap made of birch bark, between the 5th and 6th century AD. (Cultural Heritage Administration) |

Choi also wanted to clarify a misconception about the exhibition. "There was a story that most Gyeongju residents were angry with us for digging up ancestral tombs for research. This is an exaggeration. Although we did have a group of elderly come and talk about the terrible drought that year, they were not directly condemning us for the excavation. People in Gyeongju were very gentle and kind to us.”

Of all the artifacts excavated on the site, the discovery that held the greatest significance for Choi was finding the love of his life. "During my time excavating the tombs of Gyeongju, I gradually fell in love with my wife, So Seong-ok, who was also a researcher," said Choi with a smile. "She was exceptionally intelligent and diligent, as far as my memory serves."

Being the only woman in the group, she was often charged with carrying out delicate tasks. "The subtle tasks like drawing floor plans and wiping off dirt from golden relics were handed over to her, and she finished them with remarkable precision.” Love took time and patience, just like the excavation of Cheonmacheong, Choi said.