WASHINGTON (AP) ― House Republicans redoubled their efforts to roll back signature accomplishments of President Barack Obama on Tuesday, offering a slashing budget plan that would repeal new health care subsidies and cut spending across a wide swath of programs dear to Obama and his Democratic allies.

The GOP plan was immediately rejected by the White House as an approach that “just doesn’t add up” and would harm America’s middle class. Obama said the plan would “slash deeply” into programs such as Medicaid.

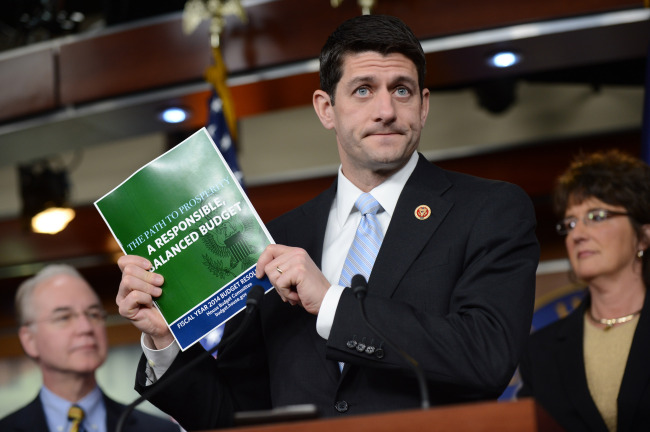

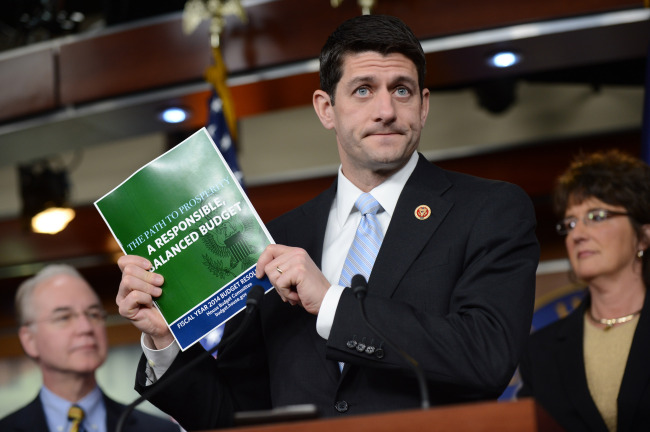

Obama has rebuffed similar GOP plans two years in a row and ran strongly against the ideas when winning re-election last year ― when its chief author, Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, R-Wisconsin, was on the Republican ticket.

|

Chairman of the House Budget Committee Paul Ryan releases the House Budget Committee’s Fiscal Year 2014 Budget Resolution during a press conference on the budget, on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., Tuesday. (UPI-Yonhap News) |

Ryan’s budget illustrates the stark differences in the visions of tea party-backed Republicans and Obama and his Democratic allies about the size and role of government ― with no obvious avenues for compromise.

Obama, in an ABC-TV interview Tuesday, said he would not seek to balance the federal budget in 10 years, as Ryan’s plan attempts to do, when he submits his fiscal blueprint to Congress next month.

“My goal is not to chase a balanced budget just for the sake of balance,” he said. “My goal is how do we grow the economy, put people back to work, and if we do that we are going to be bringing in more revenue.”

Senate Democrats are responding with a plan that would repeal automatic spending cuts that began to take effect earlier this month while offering $100 billion in new spending for infrastructure and job training. The Democratic counter won’t be officially unveiled until Wednesday, but its rough outlines were described by aides. They spoke only on condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to describe it publicly.

That plan by Senate Budget Committee Chairwoman Patty Murray, D-Washington, would raise taxes by almost $1 trillion over a decade and cut spending by almost $1 trillion over the same period. But more than half of the combined deficit savings would be used to repeal the automatic, across-the-board spending cuts that began to hit the economy earlier this month and are slated to continue through the decade.

All this was in the works as Obama trekked to the Capitol to join Senate Democrats for their weekly closed-door policy luncheon as part of his bipartisan outreach efforts to lawmakers in both House and Senate on the budget. Obama is pressing for a “grand bargain” that would attract more moderate elements from both parties ― even as this week’s competing budget presentations are tailored to appeal strictly along party lines.

Obama meets with House Republicans on Wednesday.

At issue is the arcane and partisan congressional budget process, which involves a unique, non-binding measure called a budget resolution. When the process works as designed ― which is rarely ― budget resolutions have the potential to stake out parameters for follow-up legislation specifying spending and rewriting the complex U.S. tax code.

But this year’s dueling GOP and Democratic budget proposals are more about defining political differences ― as if last year’s elections didn’t do enough of that ― than charting a path toward a solution.

“If you look at the two budgets, there’s not a lot of overlap,” said Rep. Chris Van Hollen of Maryland, top Democrat on the Budget Committee. He said the lack of “common ground” makes it necessary to make uncomfortable compromises.

One such compromise might be to adopt a stingier inflation adjustment for Social Security cost-of-living increases and the indexing of income tax brackets. House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, pressed for the new inflation measure in both sets of his failed previous budget negotiations with Obama, and the idea was favorably discussed in the “supercommittee” negotiations chaired by Murray in the fall of 2010.

But this “chained CPI” idea is nowhere to be found in either the Ryan or Murray budgets. Obama did propose the idea in his meeting with Senate Democrats ― but only as an element of a broader deficit-reduction pact in which Republicans would yield on approving new tax revenues.

“The president was pretty clear that there are pieces of the Social Security system he is willing to talk about. But he’s going to need some give from Republicans, as we all are,” said Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Connecticut.

Though White House officials say Obama would still propose the inflation measure as part of a big deal, on Tuesday they refused to say whether the president would include chained CPI in the fiscal blueprint he’s expected to deliver in April.

Driving the House GOP plan is a promise to pass a budget that would balance the government’s books, which the measure would achieve by cutting $756 billion over 10 years from the Medicaid health program for the poor and disabled, cutting deeply into the day-to-day budgets of domestic agencies and repealing new health coverage subsidies enacted two years ago with Obama’s signature health care bill.

In last year’s presidential campaign, Ryan ran against both Obama’s promise to raise tax rates on the wealthy and more than $700 billion worth of cuts to Medicare providers. But now, Ryan claims that money to help balance the budget ― as well as about $1 trillion in taxes over a decade passed by Democrats as part of Obama’s health care overhaul.

“We’re not going to refight the past, because we know that that’s behind us,” Ryan told reporters on Tuesday.

Ryan is moving on to a new battle over the annual cap for the 12 spending bills that Congress is supposed to pass each year. His budget assumes that the $1 trillion in savings over the coming nine years from controversial automatic spending cuts, just now starting, much of the money coming from the day-to-day agency budgets for the Pentagon and domestic agencies, will stay in effect.

Ryan, however, would restore those cuts to the Pentagon and instead makes domestic agencies absorb them. This double-whammy means, for instance, that non-defense appropriations would be limited to $414 billion next year ― which is $55 billion below the caps already mandated under the automatic cuts. That would likely mean gridlock when it comes time to advance appropriations bills this summer.

Ryan’s plan promises to cut the deficit from $845 billion this year to $528 billion in the 2014 budget year that starts in October. The deficit would drop to $125 billion in 2015 and hover pretty much near balance for several years before registering a $7 billion surplus in 2023.

The White House weighed in against the Ryan plan, saying it would turn Medicare into a voucher program and protect the wealthy from tax increases.

“While the House Republican budget aims to reduce the deficit, the math just doesn’t add up,” said White House Press Secretary Jay Carney. “Deficit reduction that asks nothing from the wealthiest Americans has serious consequences for the middle class.”

Ryan has also revived a controversial plan that would, starting in 2024 for workers born in 1959 or after, replace traditional Medicare with a voucher-like government subsidy for people to buy health insurance on the open market. Critics of the plan say the subsidies wouldn’t grow with inflation fast enough and would shove thousands of dollars in higher premiums onto seniors before very long.

Meanwhile, the Senate turned Tuesday to a bipartisan, almost 600-page measure for the ongoing fiscal year that serves as the legislative vehicle to fund the day-to-day operations of government through Sept. 30 ― and prevent a government shutdown when current funding runs out March 27.

Sens. Tom Coburn, R-Okla., and John McCain, R-Ariz., held up the official start of debate on the measure, complaining that they hadn’t had enough time to scrutinize it. The two are longtime thorns in the side of senators on the powerful Appropriations Committee.

![[Weekender] Korea's traditional sauce culture gains global recognition](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050153_0.jpg)