|

Illustration by Nam Kyung-don |

More equal treatment, support broaden female presence in society

His parents wish to have their first grandson.

But he wants to become the father of a pretty, endearing and, above all, smart daughter.

“I have always envied one of my superiors with two daughters, who he boasts are so sweet to him and perform well at school,” said a 34-year-old man surnamed Kim, whose wife is four months pregnant with their first child.

Kim, an employee at a financial company in Seoul, is one of an increasing number of Korean men who prefer a daughter to a son ― even if they have only one child.

This trend breaking with the country’s patriarchal tradition of making it nearly an imperative to maintain paternal lineage has become conspicuous in recent years.

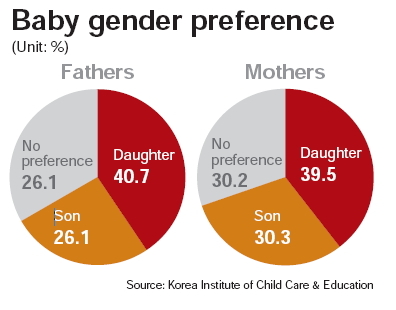

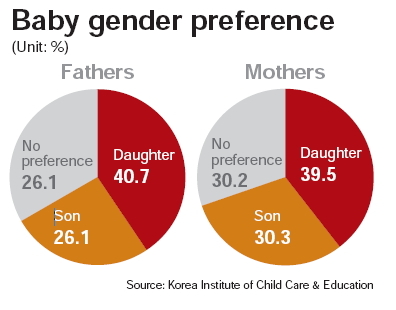

In a Korea Institute of Child Care & Education survey of 1,000 couples that had a child in April-August 2010, four in 10 fathers said they had wanted a daughter and only a quarter of them replied they had desired a son, with the others having no preference.

Among mothers, a daughter had been preferred by 39.5 percent and a son by 30.3 percent.

With such an attitude change apparently reducing sex-selective abortions, the country’s birth gender ratio ― the number of boys to 100 girls ― plummeted from the world’s second-highest at 110 in 2003 to the 19th at 106 last year, according to the CIA World Factbook.

In the latest case further boosting the preference for girls, a female cadet graduated from the Korea Military Academy at the top of her 199-member class last month.

Yoon Ga-hui, 24, who has been undergoing the 12-week training for novice Army officers, was the first woman to set the record since the school, established in 1946, began selecting female cadets in 1998.

Her parents’ delight doubled as her younger brother graduated at the same time placed 15th.

He now feels somewhat embarrassed that he once advised his sister, whose initial dream was to become an English teacher, to quit the course when she had a hard time going through physical training.

The Naval Academy and the Air Force Academy have already seen five and four female cadets graduate first since opening their door to women applicants in 1999 and 1997, respectively.

“I just respect my female colleagues for their capabilities,” said Choi Jae-hyeong, an Air Force officer. “All of them hate to be treated favorably as well as discriminated against.”

A mounting tide

The outstanding graduates from military schools are just part of a mounting tide of women who have advanced into and expanded their presence in professional fields long dominated by men.

The Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office recently assigned a female prosecutor to a department handling organized crime for the first time in its history.

The number of women prosecutors jumped from 49 in 2001 to 411 this year, with nearly one in four prosecutors now being women. In 2010, novice women prosecutors outnumbered their male counterparts by 54 to 41.

Women now make up more than 20 percent of judges and diplomats.

More than half of cub reporters recruited by major media organizations have been women in recent years.

According to statistics from the Public Administration and Security Ministry, the number of mid- to high-level female officials at administrative agencies quintupled from 420 in 2000 to 2,143 in 2010.

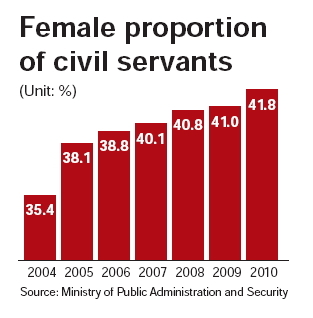

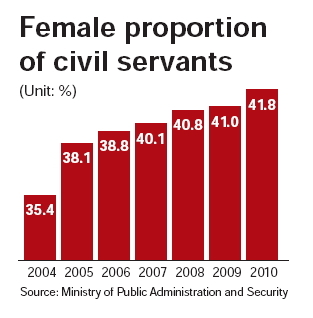

The proportion of females in the civil service rose from 35.4 percent in 2004 to 38.8 percent in 2006, 40.8 percent in 2008 and 41.8 percent in 2010, with their number climbing from 324,576 to 987,754 over that period.

In the teaching profession, women have overtaken men, accounting for 56.7 percent of elementary and secondary school teachers in 2010, up from 38.5 percent two decades earlier.

Korean voters now see three of the major parties being led by female chiefs in the run-up to the April parliamentary elections and the December presidential poll.

Some argue the female political leaders are exceptional cases, noting women are still severely underrepresented in the parliament and the top ranks of the government and corporations.

But what appears to be the prevailing mood is that they are perhaps the frontrunners of a Korea to be reshaped by the female surge.

Experts say the country will see more women making it to the top in a variety of professions in the years to come as a growing number of women rise up the ladder, elbowing out their male competitors.

Women have taken an increasing share of successful applicants for the bar exam and higher diplomatic and civil service exams, the passage of which has been regarded as opening the way for joining the elite power group.

The female proportion of successful applicants for higher diplomatic and civil service exams, which was 36.7 percent and 25.3 percent in 2001, climbed to 67.7 percent and 49 percent, respectively, in 2007 before declining slightly in the following years.

Women’s share of those who passed the bar exam more than doubled over the past decade to 37.3 percent last year.

Government personnel officials estimate the number of women who are hitting the books in preparation for the three top state-administered exams at about 36,000 last year, far above the approximately 31,000 men.

“Looking around me, girls appear to be more accomplishment-oriented, ready to pay all the costs needed to achieve their goal,” said a 28-year-old male graduate from Korea University in Seoul, who recently gave up his dream of becoming a lawyer.

Experts say women’s challenges are expected to be further intensified in future years as girls outsmart boys at elementary, middle and high schools, with female high school graduates exceeding male graduates in higher education entry in recent years.

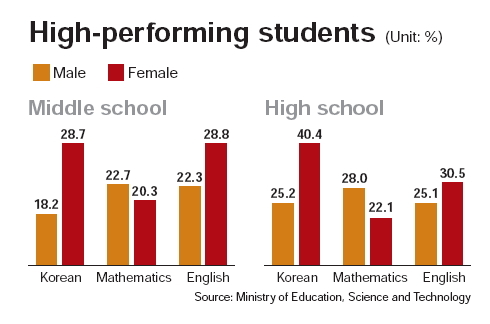

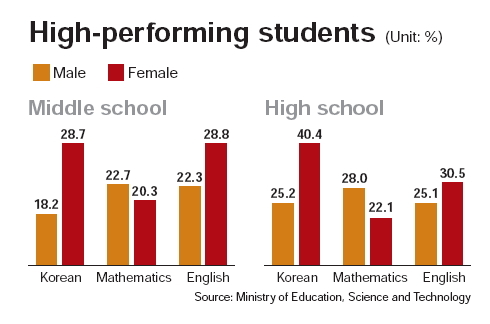

According to recent figures from the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, girl students do far better in Korean and English, while lagging slightly behind in mathematics.

At high schools, 40.4 percent and 30.5 percent of female students belong to the high-performing group, compared to 25.2 percent and 25.1 percent for male students. In mathematics, 28 percent of boys do well, surpassing girls at 22.1 percent.

Equal footing

Experts put forward a variety of explanations for the outstanding performance of women from biological advantages to changes in social environment and family structure.

What is cited by most experts as the main factor is that women are being placed on a level playing field with men.

“Our society is moving in the right direction of men and women going together,” said Moon Mee-kyung, research fellow at the Korean Women’s Development Institute, a state-funded think tank in Seoul.

She said parents have given the same care and support to daughters as sons in the nuclear family, which has replaced the traditional extended family system in the process of industrialization.

“It is no wonder women have expanded their professional presence as they are brought up to maximize their potential,” Moon said.

In the knowledge-based society, women’s traits such as sensitivity and flexibility have also helped them gain a competitive edge over men, she said.

Some also note the gender gap in the development phase, with girls usually outperforming boys in the early stage of their mental growth.

Under the current education system, in which students are required to tie themselves to their desk to get good scores, girls are more advantaged than boys, who are more outgoing and oriented toward physical activities, they say.

Many mothers, who regard society as still male-dominated and discriminatory against females, are inclined to push their daughters harder to prepare them for a competitive world, while being often overprotective of their “only” son.

This can lead many boys to be either submissive to competent girls or become violent as they grow up, experts argue.

Moon said women’s increasing professional presence is desirable for society as a whole and should never be accepted as bad news for men.

Men can be relieved of the burden of being the sole breadwinner and share it with their competent female spouses. From the viewpoint of society as a whole, women’s heightened stature can help ease men’s obligations, which Moon said have been “excessive.”

Adaptation to change

Younger generations of men appear to be more than ready to accept the changing roles and relationships between the sexes.

In a recent survey by an online dating service company of 1,030 single people in their 20s and 30s, more than 75 percent of male respondents hoped their female spouses would continue working after marriage and earn more money.

Moon advised elder generations of men, who hold most decision-making posts at public and private institutions, to change their perception on gender roles or they could be left behind.

Some experts note that putting the spotlight only on the increasing female presence may lead one to miss the whole picture, in which women still have a long way to boost their underrepresentation, particularly in the corporate sector, and overcome many barriers in the process.

The proportion of economically active women still remains at around 50 percent, compared to the figure for men, which hovers above 70 percent. Their average wage accounts for slightly more than two-thirds of men’s, with many women being employed on an irregular, part-time and temporary basis.

The burden of balancing job obligations and household work has still been placed mostly on the shoulders of married women.

In a briefing to President Lee Myung-bak on foreign affairs in January, a mid-level woman diplomat brought forth the issue of difficulties she and her female colleagues have had delivering and raising a child while changing their overseas posts.

Promising to pay more heed to the problems, Lee said, “It is as important for the country to raise a family as serving as a diplomat.”

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)