FORT WORTH, Texas ― It was a frostbitten January day 50 years ago when the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art opened its doors to the public. Only 400 people braved the threat of an icy Camp Bowie Boulevard to visit the memorial to Fort Worth’s greatest champion.

Before his death in 1955, as a final act of magnanimous boosterism, Amon G. Carter Sr., the self-made millionaire and publisher of the Star-Telegram, left instructions that his foundation would pay for an art museum for the city filled with his prized Western art collection.

“I desire and direct that this museum be operated as a nonprofit artistic enterprise for the benefit of the public and to aid in the promotion of cultural spirit in the city of Fort Worth and vicinity, and particularly, to stimulate the artistic imagination among young people residing there,” he stipulated.

A half-century later, Carter would be pleased to see that his desires were carried out to magnificent effect.

The permanent collection has grown from 400 objects to more than a quarter-million, and now represents the scope of American art from the late 18th century to the present.

The building designed by Philip Johnson became the first of three architectural masterpieces in Fort Worth’s Cultural District, and has now been enlarged three times.

The education program that Carter insisted upon is considered one of the nation’s best, serving more than 20,000 students a year.

And as it celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, the museum, as Carter intended, remains free to the public.

Carter became an art collector almost by accident. In the 1930s, a Manhattan art dealer showed him a selection of watercolors and an oil painting by Charles M. Russell. The works reminded Carter of his boyhood in Texas and, although his pockets were not deep, he wrote a $7,500 note and paid it out over the next two years.

He bought Frederic Remington’s great masterpiece A Dash for the Timber in 1945, but scored his greatest collector’s coup in 1952, when he bought the entire Charles M. Russell collection owned by the Mint Saloon in Great Falls, Mont.

|

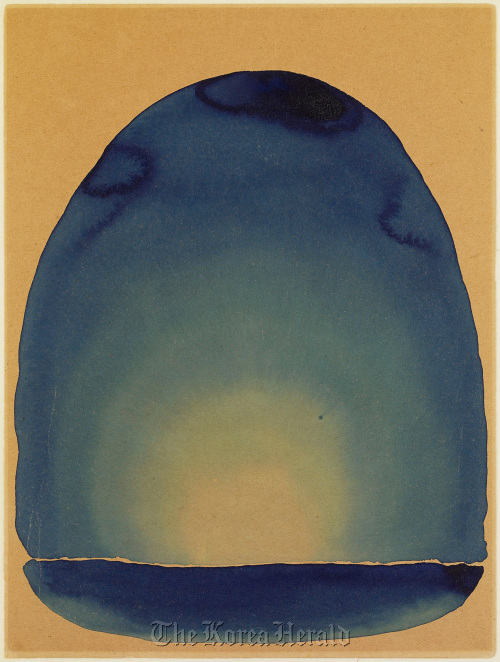

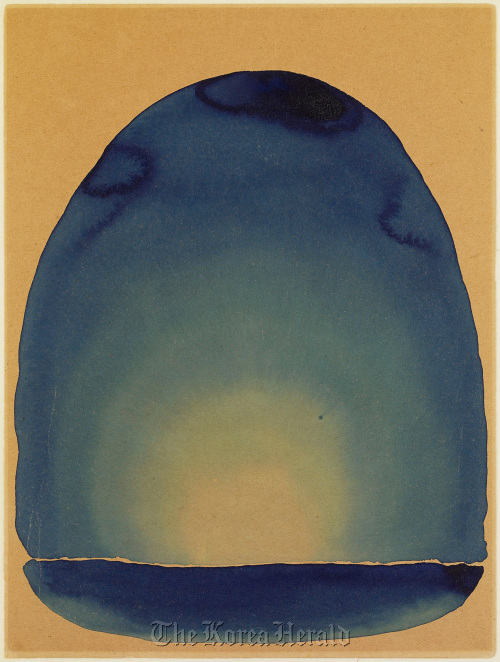

The watercolors “Light Coming on the Plains No. II” (1917) by artist Georgia O’Keeffe is part of the art collection at the Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. (MCT) |

Carter’s third wife, Minnie, did not share his enthusiasm for the Western works, however, so he installed his treasures in his office at the Star-Telegram, in his suite at the Fort Worth Club, at the Fort Worth Public Library and at Carter Field, the airport he built near what is now D/FW Airport.

At the time of his death, the collection included 100 bronzes and 200 paintings by Russell and Remington, plus watercolors, drawings, letters, books and illustrated volumes by or about the two artists.

How the museum grew to such grand proportions and influence was due in large part to his daughter, now Ruth Carter Stevenson. After her father’s death, Stevenson took charge of building the museum while her brother, Amon Jr., ran the newspaper.

She hired architect Philip Johnson, then a young up-and-comer from New York who had recently designed an annex for the Museum of Modern Art.

The memorial for Carter was a modest commission; the 20,000-square-foot building eventually came in at about $1.4 million.

The final design from the architect, who was known as a modernist, was almost classical ― three sides of the building were windowless, and the front was faced with a two-story columned facade of Texas shellstone, backed by a solid glass curtain wall. Inside were 10 small galleries, five on each floor, of an appropriate size to hang the Western paintings. Several of the galleries on the second floor were used as offices. The central hall that stretched the length of the building was used to display the bronze sculptures. The interior spaces were intimate, but the hilltop view of downtown Fort Worth was grand and expansive.

For the opening weekend, Johnson invited scores of East Coast art notables to Texas, and critics, museum directors and collectors flew in on private jets to Carter Field. The party put the museum on the art map, and the national press gave the museum’s design great reviews. Esquire magazine noted, “A fine feeling of spaciousness.” Harper’s was more effusive, “Extremely elegant.” The prescient Washington Observer noted, “With the opening of this museum, Fort Worth will have inherited a cultural legacy of national magnitude.”

During the institution’s first decade, the breadth of Stevenson’s intentions became apparent. Photographs were added to the collection, and over time this division has grown so substantially that the Carter now has one of the best permanent collections of photography in the country.

The program for exhibitions tackled subjects that required scholarly research, working with contemporary artists and mounting large retrospectives for pivotal American artists, such as the one they hosted for Georgia O’Keeffe in 1966. The education program was launched with a grant from the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities.

The Carter was off and running, but directional changes were in the wind.

It was Stevenson’s 1967 purchase of Stuart Davis’ Blips and Ifs, a rambunctious abstract painting of word fragments and flat colors, that signaled the institution’s shift of focus. The painting had nothing to do with horses, the West or cowboy ways. It was a modern masterpiece and the last work by one of America’s modernists.

Stevenson has said that her mother told her at the time, “Your father is turning over in his grave.”

Wilder explained the new direction in a press release, shortly after the acquisition.

“We have found it difficult to separate Western art and American art,” he wrote, noting that going forward, the Carter would “no longer be limited to Western art, for to understand the West, the East must also be studied.”

This broader collecting philosophy has, over the decades, established the Amon Carter as one of the premier museums of American art, and built the permanent collection to more than 250,000 objects. To acknowledge the collection’s scope, the museum officially renamed itself the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in 2010.

As the collection grew, so did the museum. It was enlarged in 1964, three years after opening, to add 14,250 square feet of space that would include offices, a bookstore, a library and an art vault. In 1977, an additional 36,600 square feet were added, with more office space, a two-story storage vault, an auditorium and an expanded library.

No additional galleries were added, however. Faced with the limited exhibition space, the storage needs of the enormous photography collection and the many outreach programs, the board once again turned to Johnson in the 1990s.

By then, the Amon Carter Museum had become what he called “the building of my career.” In 2001, when the final curtain lifted on his expanded design, Johnson was 94 years old. This time the galleries were increased 400 percent and the building filled every square inch of land, from the original facade to the apex of its triangular lot.

The original memorial, which Johnson fondly referred to as “Mr. Carter’s front porch,” remained intact. That expansion, which closed the museum for two years, cost $39 million.

The museum is planning a yearlong celebration for the 50th anniversary. Special exhibitions, events and speakers are scheduled, beginning with a photographic exhibition of the Carter’s evolution that opened late in 2010.

And although the museum officially opened Jan. 24, 1961, the big public celebration is scheduled for Aug. 13.

In 2006, Stevenson reflected on her unintentional journey in an interview with the magazine from her alma mater, Sarah Lawrence College.

“Early on, my brother and I had decided that the museum would be Dad’s memorial, not some bronze statue downtown,” she said. “I think he’d be terribly pleased with the museum today, even though he would disagree about some of the works. But he would like the way we’ve gone about using his collection and interpreting it.”

By Gaile Robinson

(McClatchy Newspapers)

(McClatchy-Tribune Information Services)