Director of the World Jewelry Museum Lee Kang-won remembers vividly an Ethiopian woman she saw 37 years ago in the corner of a local market in Addis Ababa.

The woman, dressed in a white cotton dress, was wearing a meticulously detailed, “ultramodern looking” silver necklace. Her necklace captivated Lee, who had just arrived in the country.

“Her necklace was breathtaking,” said Lee, in an interview last month at the museum in Hwa-dong near Samcheong-dong.

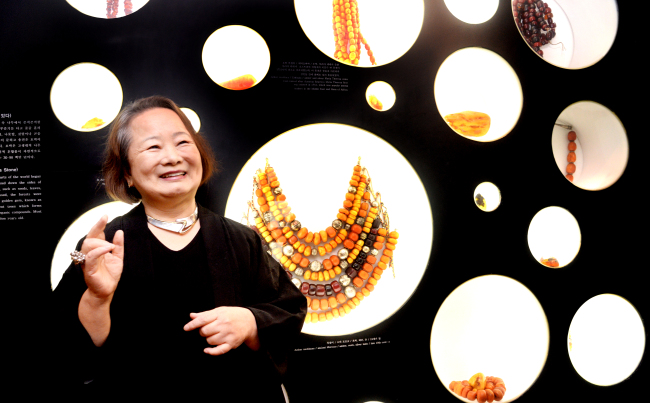

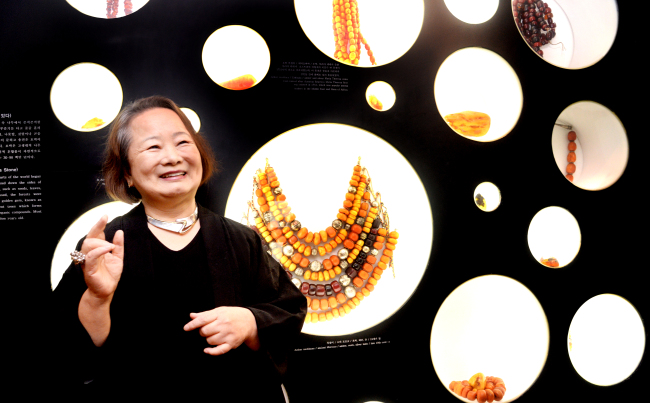

|

Lee Kang-won, director of the World Jewelry Museum, poses with her ethnic jewelry collection at the museum in Hwa-dong, Seoul. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

The handcrafted silver necklace was the woman’s wedding gift and she wasn’t selling it to anyone. But to Lee, it was the most beautiful object she had seen in the grim city, marred by violence in a civil war with her diplomat husband in 1978.

Since that day, when she began her search to find a similar necklace, Lee has become a devoted jewelry collector.

Lee collected ethnic jewelry from countries where she and her husband were stationed. She has lived abroad in eight countries, including Brazil, Germany, Ethiopia, the U.S., Jamaica, Colombia, Costa Rica and Argentina for 30 years until her husband’s retirement in 2002.

Her current jewelry collection includes more than 10,000 pieces, ranging from necklaces, bracelets, anklets, rings, earrings to masks and crosses that date from 1 B.C. to the 20th century. It is one of the largest and the most comprehensive ethnic jewelry collections in the world.

“I took advantage of my husband’s job in building my jewelry collection,” said Lee.

|

Ethiopian crosses on display at the World Jewelry Museum. (World Jewelry Museum) |

Life as a diplomat’s wife was the foundation of her jewelry collection. But she confessed that it wasn’t easy for her. “I was always balancing the tug-of-war between my official responsibility as an ambassador’s wife and my private life,” she said.

Her major diplomatic duty was hosting dinner events and preparing meals for a variety of guests. She developed Korean food recipes to suit foreigners’ palates, organized different menus for diverse occasions. She believed that the food she prepared represented Korean culture.

“A diplomat’s wife is a chef without a license,” she wrote in her 2002 book, “Tango and Guerrilla,” on her diplomatic life in Latin America.

Nevertheless, she never gave up on her passion. As a writer and poet, she published two poetry books in Colombia and Argentina, in 1993 and 2001, respectively. She became the first Asian member of the writer’s club in Argentina. She also received cultural awards from the Colombian and Argentinian governments.

Lee also observed the historic talks between the Colombian government and the guerilla movement FARC in 1999 as a freelance journalist. She became a part of the press corps after many attempts to convince Colombian officials that they needed an Asian journalist to report the landmark event.

“I was the only Asian to observe the historic peace process,” she recalled.

Looking back at her time in Latin America and other countries, she said she has had an exceptional experience.

“Three things that helped me survive in foreign countries were language, cooking and sociability,” she said. She speaks multiple languages, including English, Spanish, Amharic, German and Portuguese.

“If I didn’t speak Ethiopian Amharic, I wouldn’t have been able to build my jewelry collection.”

Acquiring a piece of jewelry required much study, research and trips to rural villages. As she was able to speak Amharic, she became friends with the local antique dealers, who shared their knowledge and information with Lee.

Each piece of jewelry in the museum tells of Lee’s dangerous, yet thrilling adventures in far-flung, exotic countries.

When she visited an Ethiopian rural village to find a rare ivory bracelet, she and her friends (other ambassadors’ wives) found themselves trapped and threatened by villagers who were afraid of their unannounced visit. She was able to explain her visit and get the bracelet she wanted from an old man in the village.

The museum’s jewelry represents many civilizations around the world and their accumulated artisanship and aesthetics passed on through generations.

A 19th-century necklace from Oman in silver, gold, and small silver beads is a work of art crafted by one of the best silver artisans in the country. Members of Oman’s royal family used to have their own jewelry artisans at home who started creating wedding jewelry for them the day they were born.

The Omani necklace, measuring some 50 centimeters in length, was put in a frame and hung at various official residences in which the Lees lived.

“This is one of the pieces that I feel most attached to,” said Lee. “It’s like the artisan’s life mortgaged by time.”

Another rare piece on display is the collection of gold sculptures of human figures and objects, made by the indigenous tribe of Muisca in Colombia. The figures visualize an ancient mythical El Dorado ceremony that was conducted by the Muisca tribe. “This is the most prized item in this museum,” she said.

Lee hopes more people come to see her jewelry collection.

“I see a long queue of people standing in front of tteokbokki or hotteok stands in the Samcheong-dong area. But not many people are willing buy tickets to the museum,” she said.

She writes columns for newspapers and lectures frequently to promote her museum and share interesting stories related to ethnic jewelries. She lectures at the Seoul branch of The School of Life -- founded by author Alain de Botton and his colleagues – and talks about jewelry collections and paintings in museums around the world on a radio show.

Lee, who served president of the association of some 140 small private museums in Seoul, noted that private museums in Korea are struggling with mounting losses and are in an urgent need of funding.

“Proceeds from selling museum tickets only cover our electricity bill,” said Lee.

Lee’s whole family is involved in the museum work. Her husband and two daughters are curators of the museum.

The Seoul Metropolitan Government offered a 1.3 billion won ($1.1 million) grant to small private museums in Seoul last year after the city officials read her newspaper column on the difficulties of running a small private museum in the city.

“I have been in debt for many years from running a museum. But I think museums are truly valuable cultural assets of a country,” she said.

World Jewelry Museum is located at 2, Bukchon-ro 5na-gil, Jongno-gu, Seoul.

By Lee Woo-young (

wylee@heraldcorp.com)

![[Weekender] Korea's traditional sauce culture gains global recognition](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050153_0.jpg)