Around 1247, Empress Hampyeong of Goryeo (918-1392) commissioned an artisan known for his skilled silver engraving to inscribe patterns of clouds and lotuses on a bronze vase in a prayer for the well-being of her family and country.

It was after her two sons were sent away as punishment for attempting to remove a general who took power in a coup d’etat, while her daughters had to marry his sons.

The vase, made for use as an incense burner at a Buddhist temple, is now considered to best represent the silver engraving technique of Goryeo dynasty for its delicate and refined lines.

|

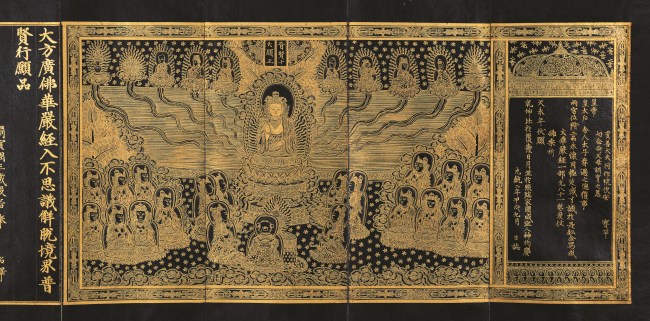

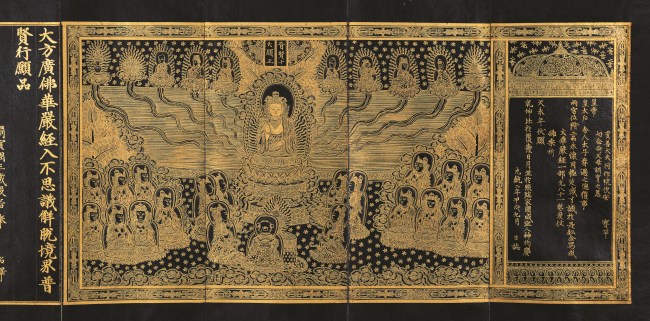

“Avatamsaka Sutra (The Flower Garland Sutra),” created in 1334. (Horim Museum) |

The glamour and opulence of Korean ancient art has largely been represented through Buddhist art. Buddhist statues, craftworks, sutras and paintings make up the majority of national treasures of Korea. And these magnificent artworks wouldn’t have existed without devout Buddhists who commissioned best artisans of their time to create them with the hope of fulfilling their wishes for peace and prosperity of their country and family.

The new exhibition at the National Museum of Korea sheds light on those patrons of Buddhist art. It reveals names of the patrons and their wishes and donations hidden behind the great works of Buddhist art from Three Kingdoms period (B.C. 18-A.D. 935) to the Joseon era (1392-1910).

“Many of the magnificent Buddhist artworks we enjoy today are the direct result of these patronage of the past,” wrote Kim Young-na, director of the National Museum of Korea, in the exhibition catalogue.

Making Buddhist artworks required spiritual support and physical donations from royalty and aristocrats. They commissioned and supported the physical making of an artwork.

As Buddhism became widespread in Goryeo dynasty, common people started making donations, expanding the class of patronage to the entire social class. Their donations varied from scriptures to colorful threads, fabrics and grain.

The Amitabha Buddha triad of Goryeo reveals a list of lower-class people, those without surnames who offered support for making the set of three Buddha statues.

The names of women show an interesting transition in women’s status from Goryeo to Joseon.

“Women were listed as individual donors during Goryeo. But they started to disappear in the Joseon Dynasty, during which they were only represented in the name of their husbands,” said Shin So-yeon, curator of the exhibition. Women’s rights started diminishing during Joseon period under the patriarchal rules of Confucianism.

The exhibition “Devout Patrons of Buddhist Art” runs through Aug. 2. For more information, visit www.museum.go.kr, or call (02) 2077-9000.’

By Lee Woo-young (

wylee@heraldcorp.com)

![[Weekender] Korea's traditional sauce culture gains global recognition](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050153_0.jpg)