ORLANDO, Florida ― Teresa Apgar once envisioned her senior years as a time of globe-trotting travel and a busy social life. Instead, she’s chauffeuring an 8-year-old to taekwondo, learning about attention-deficit disorder and supervising math homework.

“Look, I’m 58. My husband is 67. This is not where we’d planned on being at this stage in life,” the DeLand, Florida, resident said. “Everything in our lives revolves around the school schedule. It’s not like you can just dash off to Vegas.”

Like 2.9 million grandparents across the country, 150,000 of them in Florida, Apgar and her husband, DeLand Mayor Bob Apgar, have become the main caretakers for their grandchild. Their numbers have climbed steeply in recent years ― 12 percent from 2000 to 2010 ― and demographers have tracked a continuing increase going back three decades.

Financial pressures are blamed for the trend during the Great Recession, but other reasons range from parental drug abuse to incarceration to death and tragedy.

|

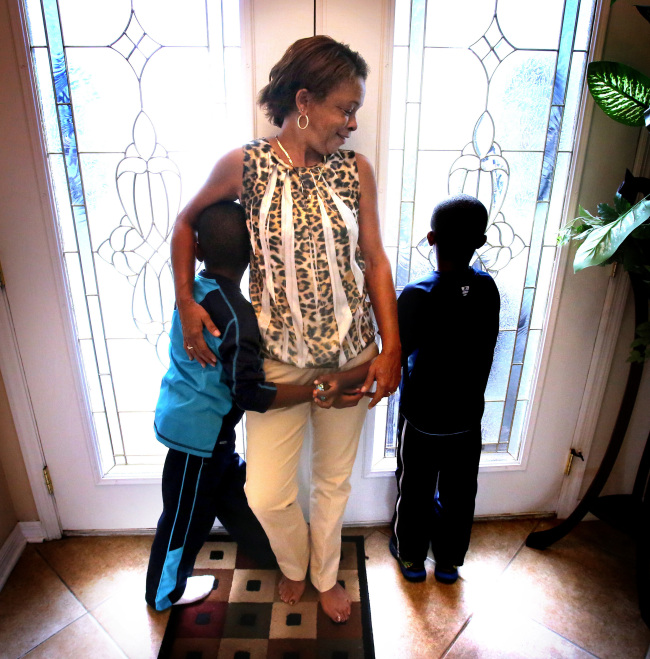

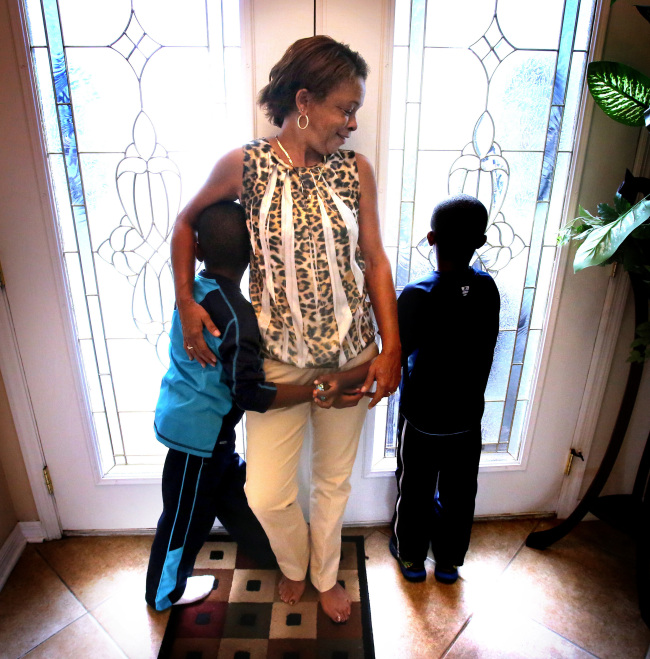

Sharon Hampton embraces her two grandsons while talking about the challenges of raising them without foster care benefits at their home in Sanford, Florida, Oct. 3. (Orlando Sentinel/MCT) |

Apgar was awarded custody when her daughter suffered severe brain damage in a suicide attempt.

“I immediately read everything I could find on grandparents raising grandchildren,” she said. “Almost all of it was this touchy-feely stuff that doesn’t tell you what it’s really like. It’s very isolating.”

The complaint is a common one. After all, it’s one thing to dote on your grandkids during a visit. It’s entirely another to be responsible 24-7 ― especially at a time in life when you may not have the energy you did a generation earlier.

But for Sharon Hampton, 58, the biggest struggle is financial. Granted custody of her two grandsons in 2010 when the parents could no longer care for them, the former Central Florida social worker had to quit work to take care of the toddlers when she couldn’t afford child care. Husband Trevor, 10 years her senior, then went back to work during what was supposed to be his retirement.

“There are a lot of grandparents out there like us who will do whatever it takes to raise their grandchildren,” Hampton said. “But it’s expensive. And I have to look at every penny I spend on myself. We have good insurance, but there’s a $30 copay to go to the doctor. For $30, I can pay for their tennis lessons for a week.”

When a severe stomach ailment sent her to the hospital recently, she ignored a doctor’s recommendation that she be admitted, instead opting to return home to care for the boys.

“When you see the smiles on their faces, when you see them laugh, when they run to you for help or crawl into the bed with us at 1 or 2 in the morning ― well, you can’t beat that kind of love,” she said. “If they were to be taken away now, it would break our hearts.”

That doesn’t mean, though, that she wouldn’t like a little more help. If she were to turn the 5- and 6-year-old boys over to the state, foster parents would be paid about $780 a month to care for them, and the children would be eligible for four-year college scholarships.

As a guardian, Hampton can get only $241 a month.

“I think more grandparents would do this ― and more children would be kept out of foster care ― if not for the financial burden,” she said.

The nonprofit advocacy group Generations United estimates that grandparents save taxpayers a staggering $6.5 billion a year in child-welfare costs ― money the government would otherwise pay to strangers to take care of the children.

“Most of these grandparents are not doing this with guardianship or custody ― most are doing it informally,” said Amy Goyer, AARP’s designated grandparenting expert. “Some of them are really, really struggling.”

On the other hand, Goyer said, many grandparents don’t realize there is some help available, even though it’s limited. The federally funded Temporary Aid to Needy Families, for instance, will give grandparents a small stipend based solely on the child’s income, which is typically zero. And in Florida, grandparents raising their grandchildren can apply for respite care so the elders can take short breaks from parenting duties.

State officials say they’re doing everything the law allows them to do.

“It’s a delicate subject when you talk to these relatives,” said William D’Aiuto, managing director for the Florida Department of Children and Families’ central region. “I understand their concern, and we appreciate them stepping up and sacrificing for these children, but the Legislature has set the caregiver and foster-care rates, and that’s what we use.”

The sacrifices can be considerable.

“The biggest hurdle my granddaughter and I had was my husband,” said Joan Hansen, a 75-year-old Orlando retiree. “He had never had children before ― and to have a child come in when we were pretty set in our lifestyle was hard for him. When she got to be a teenager and they didn’t get along, he said, ‘I don’t need this’ and left.”

Hansen was 61 when her daughter ― near the end of a hard-fought battle with breast cancer ― called the extended family to her bedside to announce her wishes for her then 5-year-old daughter.

“There was really no discussion,” Hansen said. “And I would do it all over again, no question. Sure, her rebellious years caused me some grief, but she brought me so much joy.”

Granddaughter Ashley Lynch is now 19 and in college. The two talk every day.

“I just wouldn’t be the same person without her,” Lynch said. “I feel different, but in a good way.”

By Kate Santich

(Orlando Sentinel)

(MCT Information Services)

![[Weekender] Korea's traditional sauce culture gains global recognition](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050153_0.jpg)