The year 2011 was a great year for Korean literature abroad. Writer Shin Kyung-sook’s “Please Look After Mom,” originally published in Korean in 2009, achieved international acclaim, a first for a Korean literary work in translation.

The following year, Shin received the prestigious 2011 Man Asian Literary Prize, the first Korean and the first woman to receive the prize, which recognizes the best work of fiction by an Asian writer in English or translated into English.

After years of disappointment during the Nobel season, when poet Ko Un’s name would be floated as a possible winner of the coveted Nobel literature prize, the Korean literary scene was buoyed by the news of the global success of Shin’s novel about a mother and her relationship with her family. The book was published in the U.S. by Alfred A. Knopf and in 21 other countries, including the U.K. and Poland.

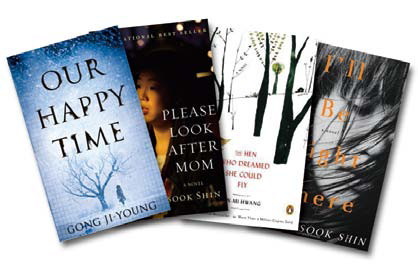

Since then, Korean literary works have been slowly gaining ground in the international scene. Children’s author Hwang Sun-mi’s “The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly,” originally published in 2000 in Korea, was released in English by Penguin Books in 2013. It has been translated into a dozen languages and won a 2012 award for the best book of the year in Poland.

Best-selling author Gong Ji-young’s “Our Happy Times” was released earlier this year in English by Short Books while Shin’s second book in English translation, “I’ll be Right There,” was recently released by Other Press.

A number of factors have been cited as contributing to the growing interest in Korean literature abroad. The first is the change in the topics the stories deal with. Whereas literary works previously introduced abroad were mostly concerned with the Korean War, the national division, democratization and the ideological divide, more recent works deal with universal themes that readers around the world can empathize with and appreciate.

Excellent translation is another crucial element for the success of literary works on foreign shores. Works by internationally renowned authors such as Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk and Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez could not have been introduced to a worldwide audience without skilled translators.

When Shin’s “Please Look After Mom” came to international attention, much was said here about the high quality of the translation by Kim Chi-young. Kim also translated “The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly.” Before the success of “Please Look After Mom” little had been said about translators and their work.

Yet, the importance of translators is not lost on writers and critics. Many of the Korean authors who participated in the London Book Fair in April pointed out the need for good translations. Speaking at a meeting with the Korean press in London, author Hwang Sok-yong was quoted as citing the lack of skilled translators who can “properly translate Korean literary works into English” as the “biggest handicap in the globalization of Korean literature.” Another literary heavyweight, Yi Mun-yol, agreed, saying that the biggest problem may be the problem of translation.

This point was reiterated last week by Kim Seong-kon, president of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea, who, in the opening remarks at the 13th International Workshop for Translation and Publication of Korean Literature, said, “For Korean authors to gain international acclaim, skilled translators, renowned publishers and competent literary agents are indispensable.”

While the need for skilled translators has gotten much attention on the back of the international success of Shin and Hwang, translators receive little recognition for their lonely, solitary hours toiling away at finding just the right word, expression or syntax. And little is understood about how they work and what makes for good translations.

At a workshop titled “The Role of Translators and Literary Agents in Globalizing Korean Literature,” held on June 20 at Coex, Andres Felipe Solano, writer and instructor at LTI Korea Translation Academy, quoted an old Italian saying: Translator, traitor. “Only a translator who understands deeply and with love the world of the author who he is translating will be capable of betraying him when necessary,” he said, explaining that a translator must have a deep understanding of the culture of the author. Solano also emphasized that translators must first of all be avid readers.

Love for literature was also emphasized by Jean-Noel Juttet, a translator and instructor at LTI Korea Translation Academy, who discussed the skills of a translator. Knowledge of the language and mastery of the target language, and a passion for literature are requirements for a good translator, he said. While the current method of translation involves a team ― one who translates and another, a native speaker of the target language, who revises the translation ― the aim should be to train translators with knowledge of the original language who can work autonomously.

Horace Jeffery Hodges of Ewha Womans University, who translates as a team with his wife, shed light on the aim of translation: To ensure that the telling of the story flows well in English even as it preserves the meaning of the Korean original.

An important element that should be taken into consideration when introducing Korean literary works to the global market is their marketability, i.e. reader interest. While there are some reservations among Koreans against translating only works that are “sellable” ― “How about Korean identity?” they ask ― selecting works that appeal to the target public appears to be the preferred approach among foreign publishers and translators.

Juttet, for example, said that for high acceptability in the French market, it would be good for translators to choose works with fantasy-like atmosphere and humor, adding that while the French public prefers such works, many Korean texts are melancholy and sad. “These are not popular with the French,” he said.

Given that the size of the market for translated works is miniscule, such a strategy may be a pragmatic one. According to John O’Brien, president of Dalkey Archive Press in the U.S., only 15 percent of the 350,000 new books published in the U.S. each year are works of literature or books about literature, and only 0.006 percent of the 350,000 volumes are literary works in translation. And it is important to gain foothold in the U.S. market as having a translation in English makes a book available to a wider readership beyond the U.S. “Countries are desperate to get into the U.S. because if the books are in English, they travel well,” O’Brien said.

In such a competitive atmosphere, the role of translators as advocates for authors and their works is becoming increasingly important. A quality translator needs to be attached to the author at the earliest stage, and the translator can act as a scout, contacting agents and sending out samples, according to Tracy Fisher of the U.S.-based WME Agency.

The importance of translators in getting the translations published was also noted by O’Brien, who said, “70 percent of our books come by our translators. It is rare that they are wrong about the book.”

So what are the genres that Korea should look to export?

“Mystery, thriller, suspense novels can most easily break out in other languages,” Fisher said, noting the popularity of Nordic and Italian mysteries as an example.

“As for Korean literature, the first wave may need to be in the more popular genres. Others can follow,” she said.

By Kim Hoo-ran, Senior writer

(

khooran@heraldcorp.com)