If music is a universal language North Korean pianist Kim Cheol-woong found perhaps one of its best uses.

On Saturday, Kim illustrated his spoken account of his journey in pursuit of musical freedom with a mix of compositions at a concert at Haechi Hall in Seoul, organized by the Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights (NKHR), for which Kim is a cultural ambassador.

Kim, who comes from an elite North Korean family, entered the stage exuding modesty and a warm sense of humor.

In between playing a harmonious mixture of classical from North Korea, Western compositions, and his own sonata, he described episodes of his life after fleeing his privileged background.

He explained that his work in the North Korean human rights movement was motivated by his desire to bring people together through music.

“We can help the cause by going out to the pickets, but that would not be the only way to help. I hope that I can bring a soft touch through my music,” he said.

Kim, 39, was trained in classical music in Pyongyang from the age of 8, learning music that was rigid in technique and restrained in expression, heavily inclined toward North Korean propaganda.

“When I was in third grade, I had to learn to play a song called ‘revolutionary army game,’” he told the audience.

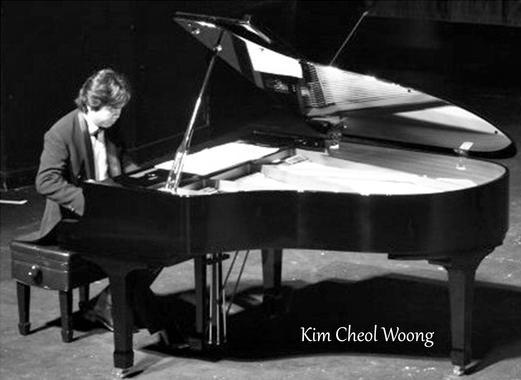

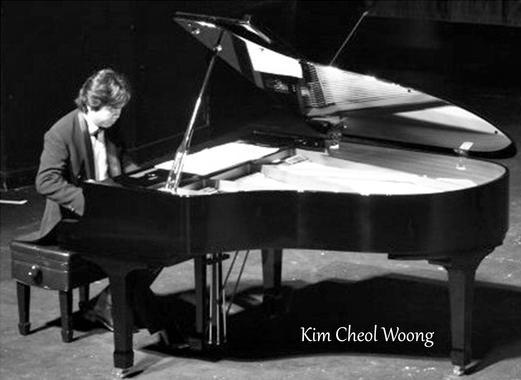

Like any maestro, when Kim plays, his fingers run across the piano keys in a synchronized dance. He described how he protected these fingers when the Chinese authorities beat him for 11 hours at a Beijing airport, by tucking them away firmly under his arms.

“It was okay for my head to break, but I had to protect my fingers,” he said.

After school, Kim had gone on to study music at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow. Upon his return to North Korea, he became the chief pianist for the State Symphony Orchestra, where he was to play only patriotic and military tunes for the leaders of the country.

|

Pianist Kim Cheol-woong plays at a concert. (www.nkhrrescuefund.org) |

One night Kim was reported to the National Security Office in Pyongyang for practicing a jazz piece by French pianist Richard Clayderman called “A Comme Amour,” for which he was asked to write a report of self-criticism.

This created a deep dilemma for Kim.

“I simply couldn’t understand why I had to write a self-criticism report, because I am a pianist, and I’m supposed to play the piano,” he said.

His decision to leave North Korea was made because of the way artists were treated, and because he wanted to play the piano freely.

“On this earth, there is one country where you can’t sing the song you want to even though you have a mouth, listen to the music that you want to even though you have ears, and play the music that you want to even though you have fingers. That is North Korea,” he said.

However, his journey to musical freedom after fleeing the regimented state was not easy. Crossing the Tumen River into China and coming to South Korea involved working as a servant for a Chinese family and being an illegal migrant in a Chinese logging camp.

The first time Kim saw a piano again was in a Christian missionary church in China, which he described as “odd looking and very amazing at the same time.”

“Out of the 88 keys, 50 did not make any sound,” he said. But Kim, who was so overcome with emotion, held on to the piano and cried.

Today, Kim’s journey of musical freedom is still underway.

He describes it in four phases: The first phase was learning the music, and the second followed with playing the music he learned under oppression in North Korea. The third was escaping this oppression and truly realizing his journey to musical freedom.

Finally, Kim is in the fourth phase, where he is trying to play music at a certain level that creates a message of faith and peace.

Since arriving in South Korea in 2001, Kim has gone on to teach music at universities, founded an arts organization for North Korean defectors, and become an advocate for North Korean Human rights.

“North Korea does not have a concept of human rights,” Kim explained. When he was first invited to a human rights forum, Kim realized that he could do more to spread awareness.

“I want to let people know that there’s nothing wrong between North and South Koreans, there are just differences. Being different is very different from being wrong. Through music, I want to focus on the similarities.”

The concert is one of many fundraising events organized by NKHR to help North Korean defectors resettle in South Korea. The organization was established to offer cultural and academic support to young people and students.

The concert was first conceived as a way of reaching out to the local community by combining two things that are internationally celebrated: music and storytelling.

All proceeds raised will help refugee rescue efforts and education programs for young North Koreans.

“Kim Cheol-woong is not only an accomplished musician, but he is also an engaging storyteller. It is very rare for North Korean defectors to be able to deliver their stories through music, so we are very happy to be working together with him,” said Lilian Lee, one of the NKHR Concert organizers.

Reunification is a key aim for NKHR, one that Kim also advocates for extensively.

One day, Kim believes his dream of being able to play with his friends from Pyongyang and South Korea together will come true.

“Dreams are something that should be realized and must be realized,” Kim said with a smile on his face.

By Astha Rajvanshi, Intern reporter

(

astha.raj06@gmail.com)

![[Weekender] Korea's traditional sauce culture gains global recognition](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050153_0.jpg)