Firms implement emissions-cutting measures, but lack concrete long-term framework

Korea is poised to blaze a trail in action against climate change by imposing mandatory emission cut targets on large companies and institutions beginning next year.

The much-touted policy, however, faces a rough ride with the affected firms by and large still lacking concrete plans, organization and resolve.

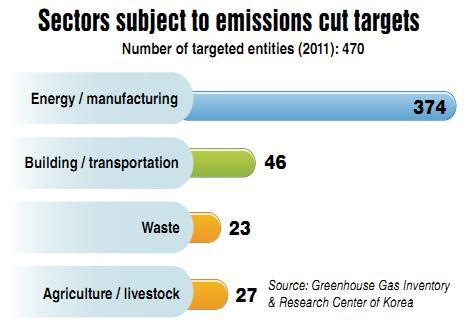

In October, the government unveiled specific targets for 366 firms, which will have to shoulder 96.5 percent of the proposed reduction in emissions.

The measures call for emissions to be slashed by 1.42 percent from business as usual projections by the end of 2012. But if firms fail to meet their target, there is no penalty except fines of up to 10 million won ($8,900). Noncompliance may also tarnish their image because their performance will be made public.

The plan was drawn up in April last year as a key measure to achieve Korea’s goal to cut emissions by 30 percent below business as usual projections by 2020. The nation is also planning to introduce a cap-and-trade system in 2015.

Among the most affected firms are POSCO, Samsung Electronics, LG Display, Hyundai Steel, Samsung Mobile Display, Ssangyong Cement, LG Chem, S-Oil and SK Energy.

Some major companies are accelerating the introduction of low-carbon technologies, renewable energy sources, greenhouse gas inventories and monitoring systems, and higher fuel economy standards.

But a majority of businesses on the list appear to be unprepared to flesh out their long-term plan. Of 26 large manufacturers quizzed by The Korea Herald, only seven responded that they had drafted plans to implement the new rules or are aware of such a company roadmap.

“We set up a task force a few years ago to carry out emissions-cutting campaigns but it doesn’t necessarily mean that we’ve set a specific goal other than the government-imposed target,” a spokesperson for a local refiner says.

Experts and companies blame their inaction on huge costs, toothless penalties, deficiency in internal communications and awareness. Also blamed is perceived uncertainty over carbon policies and markets as international commitment to climate action is dented by the economic downturn.

Kim Sung-woo, chief of climate change and sustainability in Asia Pacific at Samjong KPMG Inc., an accounting and consulting firm, points to a lack of company-wide consensus and discussion on environmental issues.

“Because most businesses address environmental and energy issues solely through a designated team, many chief financial officers or planning executives did not even know that their company became subject to the regulations when I met with them,” says Kim, who has advised a number of firms listed by the government.

“Given their existing projects, companies may face difficulties finding extra room for saving energy. That means they should reconsider their mid- or long-term plans so that they can cope with new regulations while cutting costs,” he says.

The emissions control plan sparked fierce opposition from businesses, especially energy-intensive sectors such as steel and petrochemicals, concerned about soaring costs, output losses and their disadvantage in competition with rivals from developing countries where environmental regulations are loose.

The government has extensively coordinated with industries to alleviate their anxiety. The Ministry of Knowledge Economy introduced 3 trillion won worth of loan programs and tax breaks for facility investments until 2016, as well as subsidies for research devoted to green technology such as carbon capture and storage, electric cars and energy storage systems.

“The quotas were apportioned in consideration of the technological capability to each company or institution,” says Seo Jin-hee, head of climate change policy at the Presidential Committee on Green Growth.

The government has also made penalties light. A company will be ordered to pay 3 million won in fines for the first breach. The penalty will be raised to 6 million won in the second year, then to 10 million won in the third.

“The petty fines raised questions about the plan’s efficacy,” says Hwang Suk-tae, head of the Ministry of Environment’s climate change unit.

“Though many companies are obsessed with immediate financial losses, the penalties may not provide sufficient incentives for them to get engaged in the program, and eventually in the cap-and-trade regime.”

The focal point in terms of punishment would be possible damage to companies’ reputation and trust among consumers rather than money, says Kang Hee-chan, a senior researcher at Samsung Economic Research Institute.

“We can’t really conclude at the moment whether the fines are low or high because the legislation hasn’t even come into effect yet,” he says.

“We have to wait and see if the companies fulfill their obligations to protect corporate image and brand value given that the results will be publicly posted, or they just pay fines and get away with it.”

Companies’ lack of long-term programs is also attributable to uncertainty over policy direction and the global carbon market, observers say.

The scheme is a foretaste of a national carbon trading regime under which firms will be able to emit more than allotted by purchasing credits from those emitting less than their quota.

The government aims to launch the emissions exchange in 2015. It could cut costs for the government by 68 percent compared to the cap-and-fine system, the Korea Energy Economics Institute estimates.

Yet, it is still unclear whether the government will abolish the emissions target system and completely shift to the trading scheme, or run both.

Last month, Rep. Choi Kyung-hwan of the ruling Grand National Party introduced a bill designed to add some trading features to the penalty scheme. The former knowledge economy minister is one of the most hawkish opponents of cap and trade.

“Many in the business community are still expressing concerns that we may lose our competitive edge in exports,” Choi says. “Some say it would deal a blow to our growth potential and trigger the exodus of manufacturing bases.”

The global carbon market faces dire straits with Europe, its main driver, teetering on the brink of a currency collapse.

After four years of rapid growth, the market dwindled for the first time last year to $142 billion, down nearly 1.2 percent from 2009, according to the World Bank.

The tardy progress toward cap and trade in the U.S., Australia and Japan, irregularities and fraud in the European exchange, and a fading climate commitment have combined to dampen confidence in the nascent market, the bank notes.

Global efforts lost vigor after the failure at the United Nations climate talks to seal a new accord succeeding the Kyoto Protocol, which is due to expire at the end of 2012.

“Given all those uncertainties, the government should nail down its policy framework first,” Kang says. “Companies might be waiting for that signal before mapping out their own long-term plan.”

Authorities see the trading scheme as being indispensable for the country’s 2020 goal of curbing emissions by 30 percent from 2007 BUA levels and to expedite Asia’s fourth-largest economy’s transition toward sustainable growth.

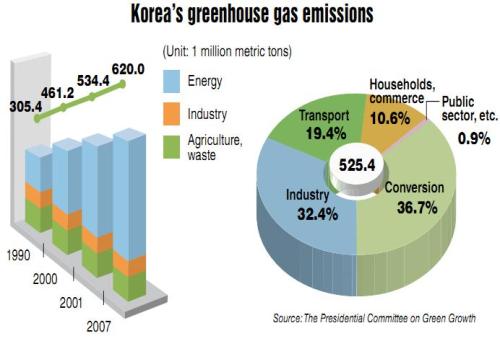

Korea is the world’s ninth-largest polluter. Its emissions have more than doubled over the past two decades, the fastest growth in emissions among OECD members. Its carbon emissions are estimated to reach 606.3 million metric tons next year.

“Lawmakers and corporate leaders should take the initiative more flexibly, looking far into the future,” says Hwang of the Environment Ministry.

“We’re not trying to clamp controls on their business but to adopt a market-oriented mechanism where they can get cost incentives. They will also be able to better deal with tightening environmental regulations when they branch out overseas.”

By Shin Hyon-hee(heeshin@heraldcorp.com)