The following is the second in a series of articles on Japan’s wartime sexual enslavement of Asian women on the occasion of the 61st anniversary of the foundation of The Korea Herald on Aug. 15. ― Ed.

GWANGJU, Gyeonggi Province ― Nearly 70 years after her release from a military brothel in China, Lee Ok-seon, 86, is still haunted by the nightmarish memories of having her dignity trampled upon by frontline Japanese troops.

At the tender age of 16, Lee, from a poor family in Daegu, was cajoled into taking a train bound for what Japanese soldiers called a “nice place” where she would have no worries about food and shelter.

“But it was a brothel where a slew of soldiers swarmed. My eyes were swollen with tears every day and I missed my mother and father so badly,” she told The Korea Herald at the House of Sharing, a civilian shelter for 10 women forced into sexual servitude by Japan during World War II.

“I couldn’t help but do as they said. You never knew what would happen should you resist the soldiers’ orders or flee. Moreover, I was too young and weak to resist the directives or just shrug them off. I had no idea whatsoever that I would be dragged into that pit.”

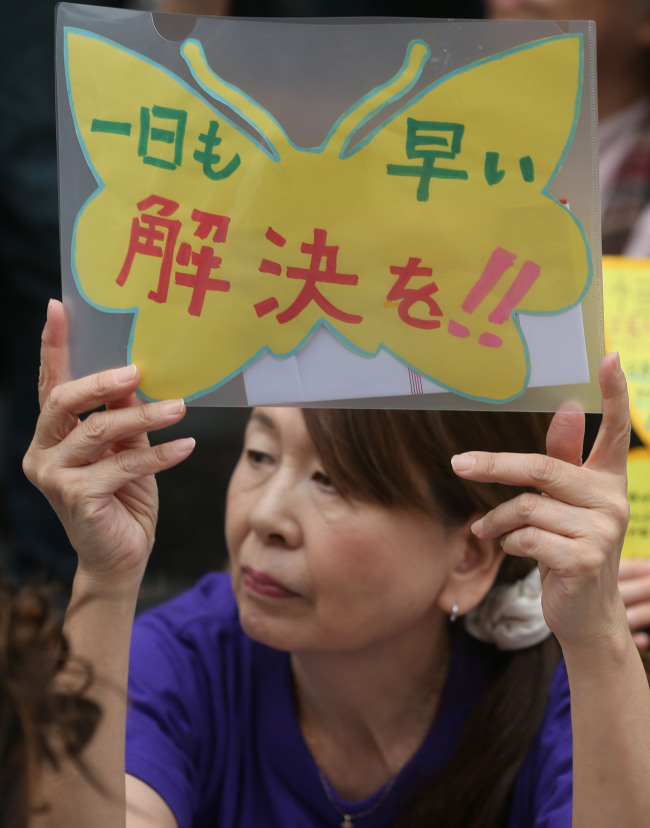

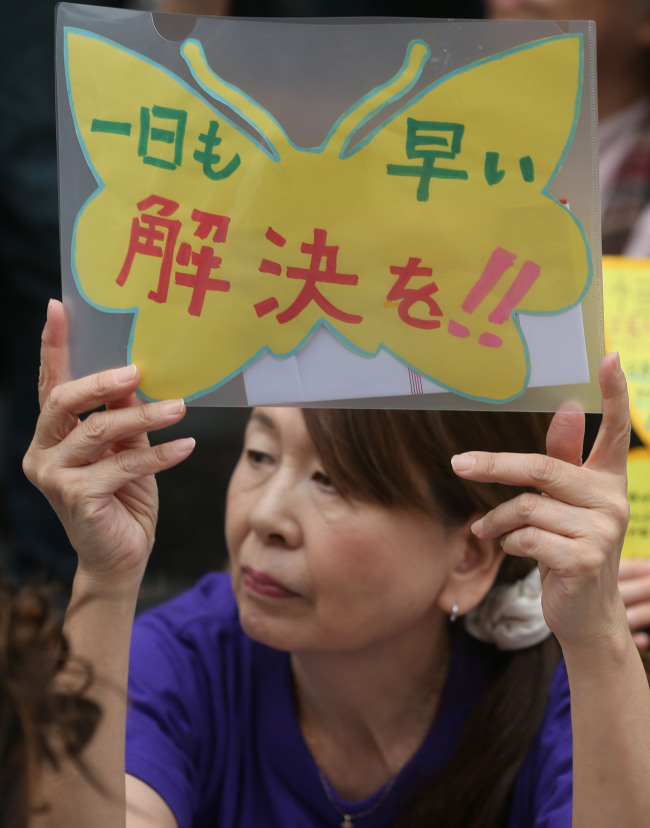

|

A Japanese activist holds a sign calling for a swift resolution to the issue of Japan’s sex slavery involving Korean and other Asian women during World War II at a weekly protest outside the Japanese Embassy in downtown Seoul on Wednesday. (Yonhap) |

Lee repeatedly used the adjective “unspeakable” in describing her psychological scars, which have continued to fester as the Japanese government refuses to fully atone for its wartime atrocities. For Lee, Tokyo’s unapologetic stance is a gruesome reminder of sexual violence at the brothel.

“How they brought me to a brothel in China, and how they treated me there and what happened there, and how I crawled back home … they were just unspeakable. I just can’t talk about every detail. They are unspeakable yet I seem to recall those days easily,” she said in a tearful, trembling voice.

|

Lee Ok-seon |

Lee is one of some 50 South Korean women still living who were forced to provide sex to Japanese troops at frontline brothels during Japan’s 1910-45 occupation of the peninsula. Historians put the total number of sex slaves, mostly from Korea and China, at around 200,000. Calling them “comfort women,” Tokyo continues to argue that there is no clear evidence that it forcibly mobilized women for sexual slavery.

“That (Tokyo’s claim) is absolutely not true. They really were Japanese troops wearing military suits and boots. I clearly remember that they, the soldiers, brought me to the brothel via train and car,” Lee said, convulsing with anger. “Well, even if Japan should make an apology, I don’t think I would be happy to accept it or appreciate it.”

After she was set free toward the end of World War II, she thought her agony would stop. But the traumatic experience festered within her, she said. To add insult to injury, she could not talk about her life in the brothel with her family or even friends, as chastity was the noblest value in the Confucian-based society.

“I couldn’t get it all off my chest. How would you tell your parents, friends or your spouse that you served in a brothel? I felt ashamed and was fearful (of social stigmas),” she said. “Thus, I thought I had to carry my deep scars to my grave.”

Kang Il-chul, 86, is another victim of Japan’s wartime sexual enslavement. Like Lee, she still suffers from memories of being raped daily by Japanese troops. The lapse of time has not blotted out the memories, reducing her to tears and causing her to quiver with resentment.

|

Kang Il-chul (Kim Myung-sub/The Korea Herald) |

Kang, from a relatively rich family in Sangju, North Gyeongsang Province, was taken by Japanese troops to a brothel around 1942, when she was 16. On her way to the brothel, she was told that she would work at a textile factory in China. But when she arrived in China, what awaited her was not factory work.

“As soon as I stepped on Chinese soil, my mind was filled with fears. Would I be able to live here? Would I be able to meet my parents and siblings again? I kept asking myself these questions,” said Kang. “I was just left speechless when I was brought there and saw many scary soldiers. I spent three years with tears and the feeling of humiliation.”

After Korea’s liberation from Japan’s colonial rule, Kang was released from the brothel. But she could not return as she married a poor Korean man living in China and gave birth to several children. Only in 2000 could she return to her home country.

In recent years, Kang has put herself at the vanguard of the efforts to let the world know of Japan’s wartime atrocities. As an eyewitness, Kang has delivered lectures and speeches at forums in Korea and abroad to call on Tokyo to squarely face up to history.

Last week, she also met the visiting Pope Francis to underscore the comfort woman issue and gave him a butterfly-shaped brooch, which symbolizes the former sex slaves’ wish to be relieved of psychological scars.

“Our younger generations should know what happened to us to prevent the repeat of such horrendous things. They should remember them and do their best to protect this country from outside invasions,” said Kang. “That is why I try to remember the disgraceful things that have happened to me and keep talking about them.”

To help the former sex victims receive a sincere apology from Tokyo, the South Korean government has underscored that the comfort women issue is an international human rights issue that goes beyond bilateral relations.

By Song Sang-ho (

sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

![[Weekender] Korea's traditional sauce culture gains global recognition](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050153_0.jpg)