Calls mounting for better safety net for aged people living alone

A 65-year-old woman surnamed Park was found dead in an apartment where she had lived alone in Asan, South Chungcheong Province, on a freezing day in February. Just two hours earlier, police had discovered a 55-year-old man, who had also been living in solitude, lying dead in a neighboring apartment.

Police officers, who visited their apartments after being told by Park’s daughter and the man’s sister that they had not been reached for days, found no traces of someone breaking in. Park’s daughter told police her mother had been receiving treatment for high blood pressure and the man’s sister said her brother had been a heavy drinker.

The deaths in the same apartment building on the same day renewed concerns over the problems Korean society is facing as it rapidly ages and an increasing number of senior citizens are living alone.

Working with private institutions and volunteer groups, central and local governments have taken measures to strengthen support for old people living alone in poverty and prevent them from dying alone. But many experts indicate more comprehensive and systematic efforts are needed to cope with the matter that will be getting more severe with demographic changes in the country.

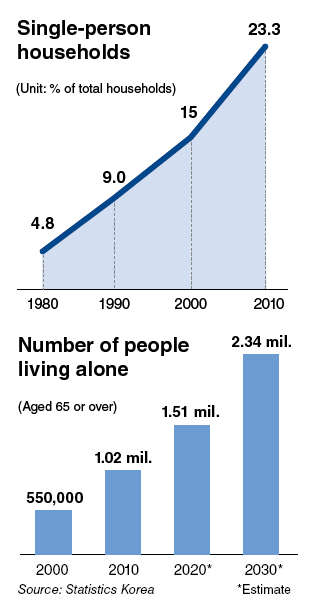

According to figures from Statistics Korea, the number of people living alone who were aged 65 or over rose from 550,000 in 2000 to 1.02 million, accounting for 20 percent of that age group, in 2010. The figure is estimated to climb to 1.51 million in 2020 and further to 2.34 million in 2030, exceeding 11 percent of the total households.

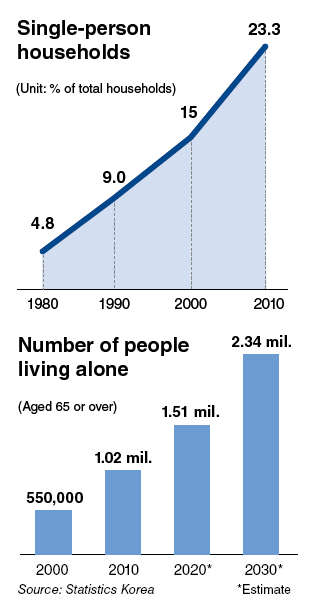

The number of single-member households was 4.03 million last year, accounting for about 23 percent of the total. The ratio, which stood at a mere 4.8 percent in 1980, increased to 9 percent in 1990 and 15 percent in 2000. One out of every four single-member households was aged 65 or older last year.

Single-member households were rare in traditional society, in which extended families were essential for the agricultural production people depended on. But with progress in industrialization and urbanization, youths left rural villages in search of jobs and new lifestyles in big cities. When one of their parents died, the other was left in a single-person household, the number of which then began to rise.

Prolonged life expectancy and changing attitude toward family have accelerated the increase in the number of elderly people living alone. People aged 65 or older are expected to account for more than 14 percent of the total population by 2018, up from 11 percent in 2009 when their number exceeded 5.35 million. According to a 2010 survey by Statistics Korea, six out of every 10 persons in the age group said they didn’t want to live with their adult children.

Vulnerable class

Government figures show the ratio of aged people living alone is relatively high in rural areas, women, people in their 70s and the less educated, suggesting socially and economically vulnerable persons are more likely to live in solitude and thus be exposed to the danger of solitary death.

“The polarization of human connections is taking place at a rapid pace in Korean society, with the underprivileged more isolated from social networks,” said Kim Yong-hak, sociology professor at Yonsei University in Seoul.

A series of surveys show most of aged people living alone suffer from economic difficulties and weak ties with their family members. According to a survey of 82,776 senior citizens living alone in Seoul, released by the city government in March, their average monthly income was 460,000 won ($430), just a third of an average monthly income for all single-member households. Another survey of 328 elderly people in rural areas, conducted by the Korea Rural Economic Institute in March, showed them in a harder financial situation, with their income averaging 422,000 won per month.

Nearly 80 percent of senior citizens living alone in Seoul suffered from at least one disease and over 66 percent did not own a home. Less than 10 percent were economically active.

Of the 66,141 who replied to a question on family contact, nearly 20 percent said they were no longer in touch with their families. More than 36 percent contacted their families more than once in a week and about 44 percent more than once a year.

The 2010 survey by Statistics Korea found less than a third of people living alone who were aged 65 or above earned their own living, with 43.5 percent depending on children and relatives, and 22.9 percent receiving support from the government and social institutions.

Aside from the two solitary deaths in Asan in February, many other cases of elderly people dying in solitude have been reported across the country this year.

An 87-year-old woman was found dead by a yogurt drink delivery woman at her apartment in Cheongju, North Chungcheong Province, last month. Police presumed she had died at least a week earlier, as bottles of yogurt drink delivered the previous week were left intact in a bag hung on the door.

A 72-year-old man was discovered by his friend lying dead at his rented house in Yangju, Gyeonggi Province, in March. The man, surnamed Chung, who had lived on 400,000 won in monthly benefits from the government, had suffered from diabetes and heart disease.

A man in his late 70s was found dead by his elder brother at his house in Jeonju, North Jeolla Province, in early February. The man surnamed Kim had lived without contacting his three daughters since divorcing his wife 10 years ago.

The risk of solitary death is even present for aged persons in daily contact with their family members. Two years ago, a woman in her late 80s was found dead by her son at her apartment in Gangnam, southern Seoul, a day after she attended church with her daughter the other day. Her son and two daughters, all of whom lived at neighboring apartments, had visited or called their mother every day to ask if she was all right.

Support programs

With a string of solitary deaths reported across the nation, the government has not yet tallied related figures. An official at the Ministry of Health and Welfare said a thorough research will be needed to take a full picture of the matter. In a possible comparison, Japan’s public broadcaster NHK reported last year that about 32,000 people died in solitude every year in Japan, which has a population of 128 million, about 2.6 times South Korea’s.

With heightened awareness of the danger of solitary death, the government teamed up with 27 institutions and companies early this year to launch a project to take care of elderly people living alone. Under the scheme, call center workers and other volunteers from public corporations and private firms like SK Telecom and Samsung Life Insurance have regularly called and visited aged persons living alone to ask after their health and form emotional ties with them.

About 36,000 people were initially selected to benefit from the program which officials say will eventually cover up to 150,000 people. “Government services have a limitation in helping elderly people living alone,” said Health and Welfare Minister Chin Soo-hee during an opening ceremony for the office to manage the program. “We need to work out a new model through cooperation among the government, private companies and community volunteers.”

The ministry is also pushing to employ an additional 10,000 elderly people in good health this year as caregivers for their less privileged peers, bringing the number of such jobs to 44,000.

Local government employees, police officers and firefighters across the country have also joined efforts to look after aged people living in solitude. In one such case, 134 firefighters in Yongsan district in Seoul have collected money for years to be delivered to elderly persons living alone each month through yogurt delivery women, whom they have also taught first aid skills. One of the delivery women has saved the life of an 87-year-old woman three times in the past three years by calling emergency services after finding her unconscious.

An increasing number of individuals also find meaning in their own lives by extending helping hands to the lonely aged.

Since 2003, a group of female volunteers in Ulsan has held birthday parties for elderly people living alone and a dozen of housewives in Gimpo, west of Seoul, have made shrouds for less privileged old persons. A 48-year-old woman surnamed Kang, who has regularly visited a 77-year-old woman living alone in her neighborhood in Seoul, said the work to take care of the old woman has made her life more lively and meaningful and served as a good example for her two sons.

|

A woman at a nursing facility in Seoul (Park Hae-mook/The Korea Herald) |

Don’t want to be a burden

Lee Myung-kun, a consultant at the Korean Senior Citizens Association, said attention should be paid to lonely aging people belonging to the first generation that supported their parents but now cannot expect their children to support them. “The aging generation has lived a strenuous life through war and industrialization, and deserves care by society,” he said.

He also said the dual attitudes of aged people living alone should be noted. A majority of elderly persons say they want to live alone, but their ulterior motive is to avoid becoming a burden to their children, he said.

A 77-year-old woman surnamed Kim recently slipped at the bathroom in her house in Seoul and tore up her forehead. She called the emergency services to take her to hospital and notified her children of the incident after having her wound stitched. “Hearing from her, I blamed my mother for not calling us immediately, but later came to think I would have done the same,” said her daughter, who was in her late 50s.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)