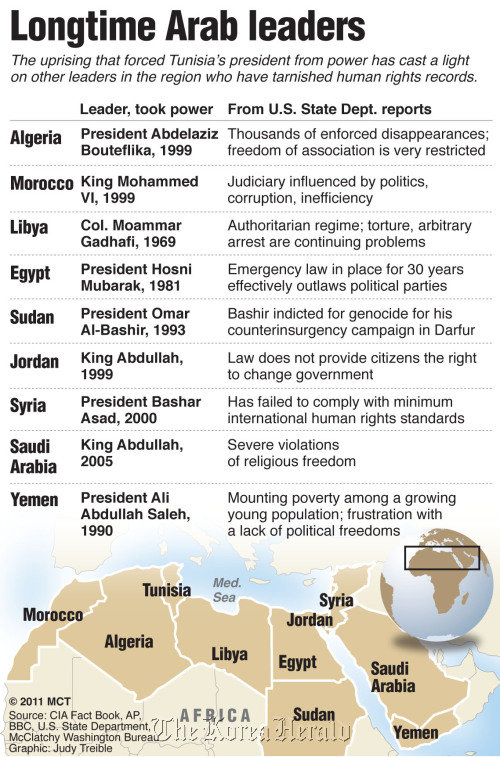

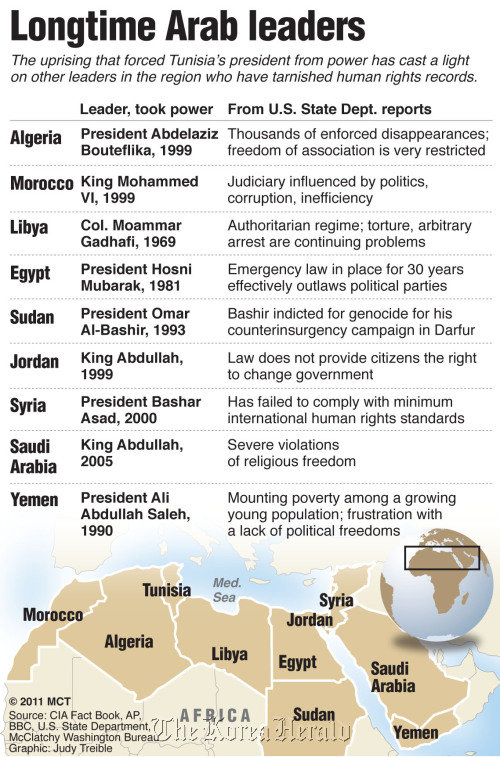

WASHINGTON ― In the three short weeks since a poor, unlicensed Tunisian fruit-seller set himself on fire after police seized his wares, protests have ousted his country’s longtime authoritarian ruler and confronted Egypt’s octogenarian president with the greatest challenge of his 30 years in power.

Thousands of Yemenis inspired by Mohamed Bouazizi’s death in Tunisia demanded an end to their ruling strongman’s 32-year reign Thursday, and political ferment has been growing in Jordan as well as energy-rich Algeria and Moammar Gadhafi’s Libya.

Tunisian flags and slogans have appeared at protests in Egypt, Yemen and elsewhere, and Tunisians are offering advice to protesters in other countries via Facebook and Twitter such as carrying goggles and scarves to fend off tear gas.

Mass protests have been called in Egypt, Yemen and Jordan Friday. Meanwhile, Lebanon appears to be headed into a new ethnic and religious upheaval.

Here are brief descriptions of the tumultuous events and the underlying causes.

Egypt

Since Tuesday, Egyptians have marched in the largest grass-roots anti-regime demonstrations since 1977 riots over bread prices. There is no single organizer, and activists, students, and ordinary people have coordinated over cellular telephones, the Internet and social networking sites.

U.S.-allied President Hosni Mubarak, who’s ruled since 1981 and is expected to try to pass the office to his son, Gamal, has received billions of dollars in U.S. military and civilian aid.

Egyptians are fed up with rampant corruption, repression, joblessness and rising prices ― issues raised in chants and on homemade signs. At least six people have been killed, hundreds injured and nearly 1,000 arrested.

President Barack Obama on Thursday urged the Egyptian government and protesters to avoid violence. Answering questions via YouTube, he insisted that he had pressed Mubarak in the past about political and economic overhauls, and said Egypt’s government must provide its people “mechanisms in order to express legitimate grievances.”

In the past, Washington has mostly ignored the regime’s mass arrests and indefinite detention of political prisoners, particularly activists of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood.

Yemen

Tens of thousands of people marched Thursday in the capital, Sanaa, demanding an end to the 32-year rule of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who’s been accused of corruption, nepotism and human rights abuses in one of the Arab world’s poorest countries.

Saleh also has angered Yemenis by allowing U.S. drone strikes on suspected al-Qaida targets inside Yemen in exchange for a dramatic increase in U.S. counterterrorism aid.

He is struggling with a rebellion by ethnic Houthi rebels in the north, a budding insurrection in the south and violence by an al-Qaida faction that has staged several failed terrorist attacks against the U.S. Many Yemenis customarily carry guns.

New protests were expected Friday, but Yemen’s political opposition is fractured and it’s uncertain if the mostly young demonstrators can sustain their momentum.

Saleh has tried to defuse tensions, denying that he is grooming his son to succeed him and offered to talk with his opponents. The government organized its own pro-Saleh rallies Thursday, but turnouts were low.

“The opposition is calling for change of regime but they don’t have answers,” said Faras Sanabani, an adviser to Saleh’s regime. “And I can assure you that people here don’t want violence because then you would have 5 million guns in the streets, and people know how dangerous it is for the country to go into chaos.”

Tunisia

Tunisia’s spontaneous popular uprising, which ousted authoritarian President Zine el Abidine Ben Ali, gave hope to pro-democracy activists in a region led by intractable monarchs, dictators and dynasties.

|

Protestors burn a photo of former Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali during a demonstration in Tunis against holdovers from Ben Ali’s regime in the interim government. (AP-Yonhap News) |

However, Tunisians continue to protest daily in hopes of creating an interim government without any Ben Ali-era figures, and the state is struggling to restore order since the president’s Jan. 14 ouster.

It remains to be seen whether Tunisians will achieve one of their main goals: hauling Ben Ali back from exile for a public reckoning of his regime’s alleged abuses.

Algeria

Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s military-backed government has been making major international grain purchases in an apparent bid to avoid higher prices in coming weeks.

That’s because as the turmoil raged in Tunisia, violent protests over government-ordered price increases for flour and other basic foods roiled Algeria. Bouteflika enacted some price reductions, but many experts are predicting further unrest.

Algeria is the world’s ninth-largest crude oil producer, but poverty and corruption are rampant. Unemployment in the country of 36 million is 25 percent, according to independent estimates.

The country remains under a state of emergency imposed in 1992, when the army seized power and canceled elections that would have brought an Islamic fundamentalist party to power and igniting a civil war in which an estimated 200,000 people died.

“Restrictions on freedom of assembly and association ... significantly limited citizens’ ability to change the government peacefully through elections,” the State Department’s 2009 human rights report said of Algeria.

Bouteflika, 73, won a third five-year term with 90 percent of the vote in 2009 polls that were boycotted by major opposition parties and denounced as fraudulent by critics.

Lebanon

Lebanon’s crisis differs from the unrest rocking other Arab countries, rooted in religious sectarianism more than poverty and political repression, and involving Iran and Syria, countries long at odds with Washington.

Hezbollah, the Shiite Muslim militia movement that has gained power in recent years with Iranian and Syrian backing, pulled out of the Cabinet on Jan. 12, bringing down the government of U.S. ally Saad Hariri, a Sunni Muslim.

Hezbollah’s goal, analysts say, is to halt Lebanese cooperation with a U.N. tribunal investigating the 2005 murder of Rafiq Hariri, Saad’s father. The tribunal is soon expected to name Hezbollah figures in the murder.

This week, Hezbollah had its candidate, businessman Najib Miqati, named prime minister. That sparked protests by Hariri’s mainly Sunni Muslim and Christian backers, and renewed concern of a return to the mayhem that raged in the 1970s and 1980s.

The danger is that “as tension between the two communities persists, we are going to see the potential for long-term damage,” said Mohamad Bazzi of the Council on Foreign Relations.

By Jonathan S. Landayand Warren P. Strobel

(McClatchy Newspapers)