|

A mock-up of the flying car Butterfly currently being developed by Hanwha Systems and Overair (Hanwha Systems) |

South Korean conglomerates Hanwha Group and Hyundai Motor Group are in a tight race to develop flying cars, with an aim to launch a commercial air taxi service in the next four to five years.

If realized, the service would address many urban problems like traffic congestion and air pollution. It could fundamentally change the way people commute, work and live, the companies say.

Technology-wise, the firms are not far off from building a passenger craft that takes off and lands vertically. The real question is the infrastructure, the regulations and public acceptance of this brand new class of transport, dubbed urban air mobility or UAM. Price, too, will be a crucial issue for its commercial takeoff.

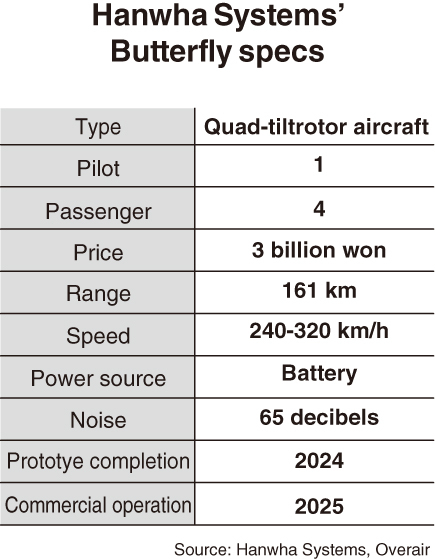

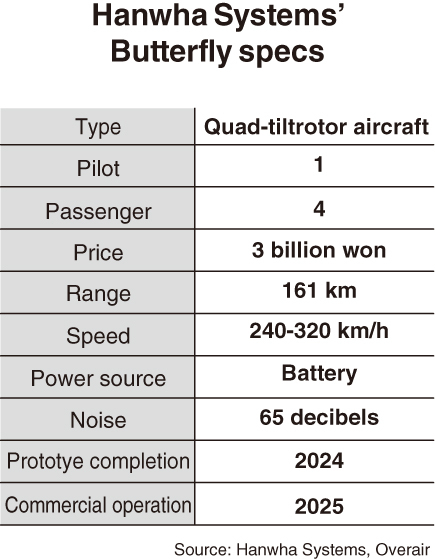

At the Seoul Mobility Expo held this month, Hanwha Systems unveiled a mock-up of its flying car known as Butterfly. It looked good in almost all aspects -- sustainable, safe, fast and quiet. The only catch was that it is as expensive as 10 Lamborghini Huracan supercars.

Can the developers really bring costs down to make flying taxi rides a part of daily life?

Affordable for the masses?

Butterfly is a joint undertaking of Hanwha Systems and Overair, a US-based personal air vehicle specialist.

It is envisioned to produce zero direct emissions, being powered entirely by batteries. Even if one of its four rotors fail, the flying car would still continue to operate. At a speed of 320 kilometers per hour, it could travel from Yeouido, western Seoul, to Suseo, southern Seoul, in five minutes, which would otherwise take 50 minutes by subway. Also, Butterfly would be no louder than 65 decibels, which is quieter than a vacuum cleaner, according to the product specifications released by the companies.

But the build cost is a whopping 3 billion won ($2.6 million).

To compare, HeliNY, a helicopter flight service firm in the US, operates the Bell 407, a $2.6 million chopper, and charges six people $1,655 for a five-minute one-way trip from Teterboro Airport to New York City.

Aiden Chung, a manager at Hanwha System’s UAM strategy and planning team, says a flying taxi service has key advantages that would make it cheaper than the helicopter service.

“Helicopters are fueled by oil, so they’re susceptible to fluctuations in oil prices. Also, flying cars use motors and have simple structural designs, while helicopters require frequent parts changes and a big team of engineers for maintenance. As flying cars produce zero emissions, subsidies are expected from the government,” he said.

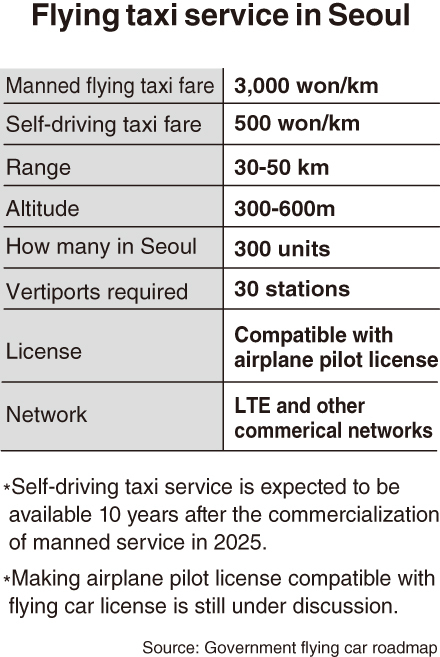

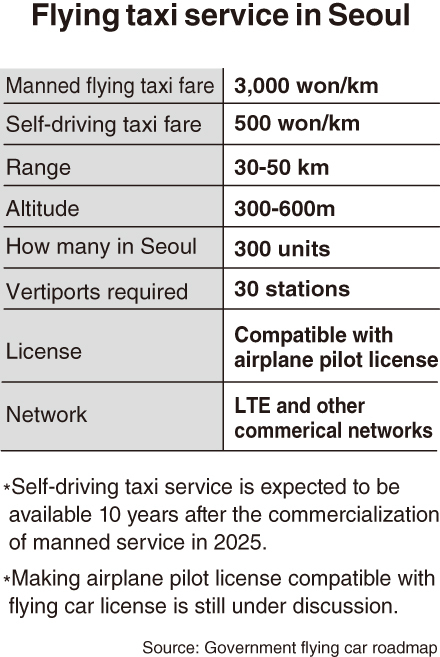

According to a road map drawn up by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, a flying taxi service will cost 3,000 won per person per kilometer in the initial stages. When the service becomes fully autonomous after 2035, the figure is projected to drop to 500 won. This means that a 20-minute-ride from Incheon Airport to Yeouido, western Seoul, a distance of about 40 kilometers, would cost 120,000 won per passenger initially, but could become as cheap as 20,000 won.

Autonomous flying will dramatically bring down the price of the service but this could take longer than expected.

According to a survey conducted by the Korea Transport Institute, 59 percent of respondents said they would feel “positive” riding a flying taxi with human pilots. When asked about riding a self-driving flying taxi, only 27 percent of them responded positively and 49 percent said they would not.

The government is expected to require human pilots onboard for some time after the service’s commercial launch to address safety concerns.

Infrastructure, a real challenge

For flying cars to become reality, they would need to soar above the walls of regulations and existing urban infrastructure settings. This is why some industry insiders fathom the arrival of the urban air mobility era in near future.

Indicative of the many complex issues to be addressed for air taxis to take off, there is a heated debate going on over who should be entitled to drive it – an airplane pilot or helicopter pilot.

As a flying car takes off and lands vertically like a helicopter but flies horizontally like an airplane, it hasn’t been decided which category it belongs to and which type of license its pilots should have.

Airplane and helicopters pilots are colliding over the license issue, as the flying taxi industry is projected to generate 300 pilot jobs in the future. Viewing flying cars as airplanes is currently gaininig momentum, as a flying car lacks a key component of a helicopter called “swashplate,” a device that transmits the pilot’s commands to the rotating rotor hub and blades.

“There is a prevailing view that flying cars are airplanes because they fly with simple propellers, not with complexly designed swashplates,” an industry official said.

A plan is currently under review to issue the flying taxi license to airplane pilots if they take special training.

On top of the licensing issue, flying taxi service requires massive infrastructure investments to establish parking spaces.

According to the transport ministry, it will take 30 docking stations, or vertiports, in Seoul to accommodate some 300 flying taxis.

Building a vertiport in the city would cost about $15 million, while a large-scale one on the outskirts would take $60 million, according to estimates from Corgan, a design and architecture firm in Dallas that designed a vertiport for Uber’s flying taxi unit Elevate. Uber sold off Elevate to California-based electric aircraft developer Joby Aviation in December.

Last month, Hanwha Systems unveiled a concept image of its vertiport, which basically looked like a parking lot the size of a small baseball field. The envisioned facility has three pads for a stand-by and one pad for landing and take-off. Also, it is equipped with chargers, a maintenance booth, an air traffic control center, a firefighting facility and a resting area for pilots, and therefore requires a lot of space. Hanwha hasn’t purchased land for its vertiport yet.

Compared to Hanwha’s spacious vertiport, Hyundai’s model offers a design resembling a fountain that puts emphasis on maximum efficiency. The two-story vertiport has a waiting area for passengers on the ground floor with 10 entrances and an open docking pad on the second floor.

Some suggest the abundant helipads on the rooftops of buildings in the capital could be converted into vertiports, but others say that it is a tempting but unrealistic idea.

While it could be cheaper than building a whole new facility from scratch, most of the existing helipads on the rooftops are for emergency purpose and very rarely use. They’re not designed to withstand the stress from constant landings and take-offs. Rooftops of ordinary buildings would have to be tested for structural integrity as well.

Above all, such a plan can only be realized when companies win the confidence of regulators as well as the those residing in the neighborhood about the safety issues. If unsure, regulators wouldn’t allow them to fly right above densely populated areas, as a fall would result in mass casualties.

“If Hanwha chooses to utilize rooftops as vertipads, candidates would be locations that have a symbolic meaning such as shopping malls, hotels and trade centers,” Aiden Chung said.

Speaking of safety concerns, what is the option for passengers if a flying car shuts down due to system failures or battery fires for instance?

According to Hanwha Systems, Butterfly passengers can escape with parachutes and the flying car will be guided to make an emergency landing in a river or field. As Butterfly is designed in the shape of a glider, it can descend slowly instead falling out of the sky.

In addition to physical infrastructure such as vertiports, a flying taxi service requires software support -- a 3D map to navigate through corridors between high-rise buildings.

Currently, how exactly high flying cars can travel hasn’t been decided yet, but the altitude between 300 meters and 600 meters is likely to be allocated, according to the transport ministry.

In South Korea, there is only one provider of a 3D map service – Naver.

Last year, Naver Labs, the research arm of Naver, created a digital twin of Seoul. Using its artificial intelligence, Naver converted 25,643 aerial photos of 605 square kilometers of the city into a high-definition 3D map. Dubbed “Alike,” the solution offers a 3D modeling of approximately 600,000 buildings in the city.

“The fees for using Alike is confidential, but the it is a capital intensive business,” a company official said.

A rivalry building up

There is also a matter of jurisdiction and standardization, which is why Hanwha and Hyundai Motor have competitively forged an air taxi alliance of their own, with airport operators and other players. The two sides have to settle out their jurisdictions, as boundaries remain blurry at the moment.

Hanwha, thanks to its partnership with Korea Airports Corp., has business rights of flying car service at the nation’s 14 airports including Gimpo Airport. However, Hanwha doesn’t have control over Incheon Airport, the largest airport of the country, as Incheon International Airport Corp. is in partnership with Hyundai Motor.

|

A rendering image of a flying car Hyundai Motor and Uber once developed together. The partnership fell apart in December when Uber sold off its flying taxi unit Elevate. (Hyundai Motor) |

Simply put, Hanwha can roll out a flying car service at all airports in the nation except the most important one -- Incheon Airport.

The transport ministry has formed a task force with representatives from both Hanwha and Hyundai Motor coalitions to iron out details, but many questions remain unanswered, whether the two sides will operate a unified air traffic control system or separate ones, for example.

On top of the jurisdiction issue, there is a matter of standardization. To commercialize flying cars, the government will have pick a model and set it as an industry standard, and Hanwha seems to be taking the lead.

Hanwha, which acquired a 30 percent stake in a US-based air taxi startup Overair at $25 million in January last year, aims to develop a prototype of Butterfly by 2024 and begin a trial operation starting 2025.

In contrast, Hyundai Motor, whose partnership with Uber fell apart in December, is facing major uncertainties and doesn’t have an official specification of a prototype. In January last year, Hyundai Motor became the first automaker partner of Elevate, Uber’s flying taxi business. In December, however, Uber sold off Elevate to Joby Aviation.

Now, Hyundai Motor is independently developing a prototype with the aim of commercializing flying cars for logistics business in 2026 and those for taxi services in 2028. The carmaker recently teamed up with Korea Aerospace Industries, the country’s sole aircraft manufacturer, and LIG Nex1, a drone and missile maker, to come up with a prototype. Hyundai Motor hasn’t revealed an official specification of the prototype yet.

On June 14, Jose Munoz, the global chief operating officer at Hyundai Motor, told Reuters that the company might kick off air taxi service before 2025, which is three years ahead of schedule, as preparations are being made faster than expected.

“During task force meetings, government officials mainly ask about the speed and the completion date of the prototype, as the government would have to run tests as soon as possible. We believe the two factors will decide which prototype will become the industry standard,” a Hanwha Systems official said.

By Kim Byung-wook (

kbw@heraldcorp.com)