Mounting allegations of forced labor in the Chinese region of Xinjiang have posed a conundrum for the global solar industry, and some say they could also drag down South Korea’s ambitious solar plans.

Located in China’s far northwest, the region rife with allegations of human rights abuses is home to four of the world’s top five producers of polysilicon, a key raw material for most solar panels. Together, those four plants account for 40 percent of the global supply.

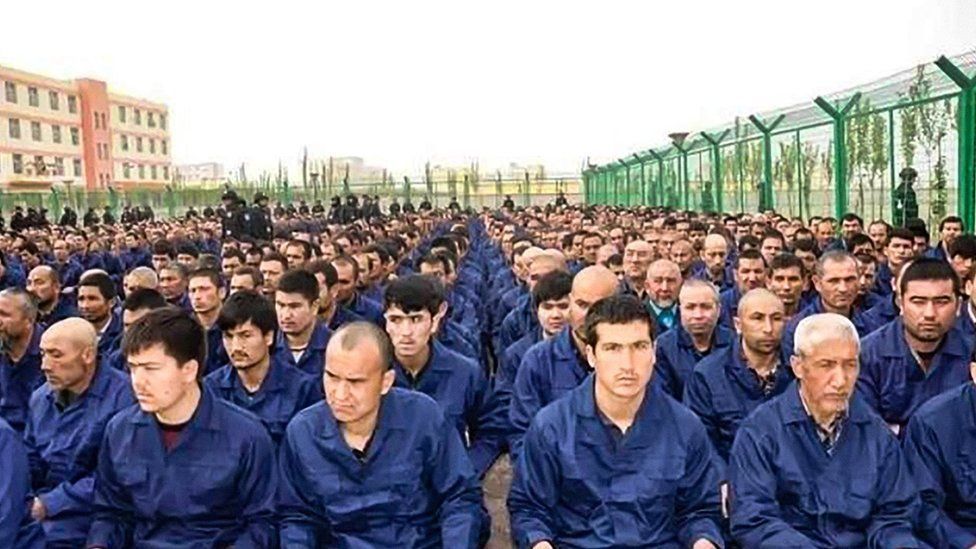

In January Washington banned cotton and tomatoes produced in Xinjiang amid reports that Uyghurs -- members of a mostly Muslim ethnic minority group there -- are detained in camps and forced to work under subpar conditions in factories and farms.

China has denounced the claims as yet another political move from the West to sabotage the country’s growing presence in the global solar supply chain. The country’s share of the global polysilicon market increased from 26 percent to 82 percent between 2010 and 2020, while that of the US shrank to 5 percent from 35 percent.

“Nearly every silicon-based solar module -- at least 95 percent of the market -- is likely to have some Xinjiang silicon in it,” said Jenny Chase, head of solar analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

Korea, diplomatically squeezed between its close ally the US and its economic trading partner China, remains quiet on the issue, apparently trying to stay away from trouble.

Yet the matter will soon affect Seoul too, experts say, as long as it continues its ongoing solar energy drive under President Moon Jae-in’s Green New Deal initiative, which will create demand for the cheap Chinese imports potentially linked to forced labor.

Secrecy, taboo surround Xinjiang polysilicon use There is no official data available to gauge Korea’s dependence on Xinjiang polysilicon.

But it is clear that imports of cheap Chinese solar panels have grown significantly in recent years, riding the solar boom here.

Data from the Korea Energy Agency shows Chinese imports accounted for 32.6 percent of the solar panel market as of the first half of 2020, sharply up from 21.6 percent in 2019. Separate data from the Korea International Trade Association show Chinese products made up 98.4 percent of all solar panels imported to Korea from January to June 2020.

The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy of Korea said the photovoltaic panels manufactured in Korea contain “almost no” Xinjiang polysilicon in response to an inquiry from The Korea Herald. It did not elaborate on the statement, nor did it reveal the origins of the polysilicon in those imported products.

Manufacturers in the solar industry contacted by The Korea Herald said the word Xinjiang has become something of a taboo now.

“When we discuss business with suppliers in China, they feel very uncomfortable with even using the word ‘Xinjiang.’ When we asked why, they said that ‘the word’ is being censored by the Chinese Communist Party. Just mentioning Xinjiang has become a taboo in the solar industry,” said an official from a major Korean solar cell and panel manufacturer who spoke on condition of anonymity.

The official said boycotting Xinjiang polysilicon is a matter of will. For products exported to the US, the company doesn’t use Xinjiang polysilicon at all.

But for the Korean market, the company admitted it uses a “small amount” of Xinjiang polysilicon for price competitiveness.

The presence of Xinjiang polysilicon in imported goods may be higher than what the government claims, as another Korean solar cell and panel manufacturer said it didn’t even ask whether its suppliers used Xinjiang polysilicon or not, because they aren’t legally obligated to disclose such information.

Distancing attempt While trying to avoid getting involved in the forced labor issue, Korea initially appeared to have found a way to curb Chinese panel imports temporarily, although this was done for a different purpose.

The “carbon certification system,” introduced in July last year, seeks to give greater government incentives to solar energy developers choosing panels certified as low-carbon products.

Due to the coronavirus outbreak, inspectors from the Korea Energy Agency weren’t able to conduct site visits overseas and thus couldn’t assign grades to Chinese solar products.

But as a result of complaints from Chinese solar manufacturers in January, the agency began to allow the panel makers to instead submit documents on how much carbon is emitted during production.

The Chinese government is also moving quickly to make the solar industry more eco-friendly, in accordance with carbon footprint systems operational in more than 40 countries around the world.

“Due to the carbon certification system, Chinese solar modules won’t be able to dominate the Korean market for the time being. However, if China keeps expanding its renewable energy sector, Chinese products will have a greater influence in Korea,” said Korea Photovoltaic Industry Association Vice Chairman Chung Woo-sik.

Xinte, which runs an 80,000-metric ton polysilicon factory in Urumqi, Xinjiang, announced Feb. 9 that it would build a 200,000-ton plant in Baotou, Inner Mongolia. The factory, slated to open as early as late 2022, is set to become the world’s largest polysilicon production complex.

For the operation of the Baotou plant, which will require 10 gigawatts of electricity per year, Xinte will source electricity from solar and wind power plants instead of coal-fired power plants in an apparent effort to avoid criticism from Western countries.

Strategic thinking neededWhile the US has been the most vocal on the Xinjiang issue, Europe appears to be more cautious for now, trying to avoid aggravating China by slapping it with trade sanctions.

There is a growing uneasiness within the global solar industry as well, although real action to actually boycott Xinjiang in the supply chain appears yet to come.

In February, some 175 members of the Solar Energy Industry Association in the US signed a pledge to eliminate suppliers linked with forced labor allegations from their supply chains. Two Korean solar manufacturers joined this pledge -- Hanwha Q Cells and LG Electronics.

“(China) controlling the global solar market with cheap polysilicon made by slaves seriously undermines the competitiveness of solar companies in other regions who are paying the fair price for manufacturing their products,” said an energy professor in Korea who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter.

For Korea, taking a stance on the Xinjiang issue carries big risks, experts say.

“Korea can’t afford to ban the import of Chinese solar products which may contain Xinjiang polysilicon because the costs will be ultimately shifted to the customers and slow down the pace of President Moon’s Green New Deal initiative,” an official from a major solar manufacturer said.

As part of the Green New Deal initiative, Korea is preparing to shut down 30 coal-fired power plants and quadruple renewable power capacity, mostly solar and wind energy, to 84.4 gigawatts by 2034 from 20.1 gigawatts as of 2020.

Last year, the country installed 53,454 new solar farms worth 4.1 gigawatts, a record annual increase, according to the Korea Energy Agency. The record is set to be broken, as another 4.4 gigawatts are planned this year.

“Korea cannot and should not approach the Xinjiang polysilicon issue from a simplistic perspective of human rights. Korea must navigate carefully its political and economic interests over the issue, unless it wants to be penny-wise and-pound foolish,” Yuanta Securities analyst Hwang Kyu-won said

“If South Korea decides to side with the West, it can give China the excuse to take ‘proportionate’ economic retaliation against Korea such as banning Samsung smartphones in the domestic market, for instance.”

The analyst added that taking a clear stance on the matter could be “extremely dangerous” for Korea, especially when the country is taking the middle road in diplomacy. Currently, Korea is not included in the Quad, an informal strategic alliance consisting of the US, Japan, India and Australia that aims to confront challenges from China.

By Kim Byung-wook (

kbw@heraldcorp.com)

![[Weekender] Korea's traditional sauce culture gains global recognition](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050153_0.jpg)