The Moon Jae-in administration’s employment policy, which relies on fiscal spending and is unaccompanied by regulatory and labor reforms, will do little to ease Korea’s deteriorating situation of youth joblessness, experts say.

What is further concerning is that a set of pro-labor measures taken by the administration is pushing an increasing number of local firms to move production abroad, reducing jobs at home.

The Ministry of Strategy and Finance is drawing up a supplementary budget worth 4 trillion won ($3.74 billion) to fund various programs announced last week to induce more young people to work at small and midsized enterprises by subsidizing wages and offering income tax exemptions.

Such programs had been worked out after President Moon in January called for “extraordinary” steps to tackle youth unemployment, which he said could cause a national disaster if left unaddressed.

The jobless rate of people aged 15-29 stood at 9.8 percent at the end of February, more than twice as high as the overall unemployment rate of 4.6 percent, according to data released by Statistics Korea last week.

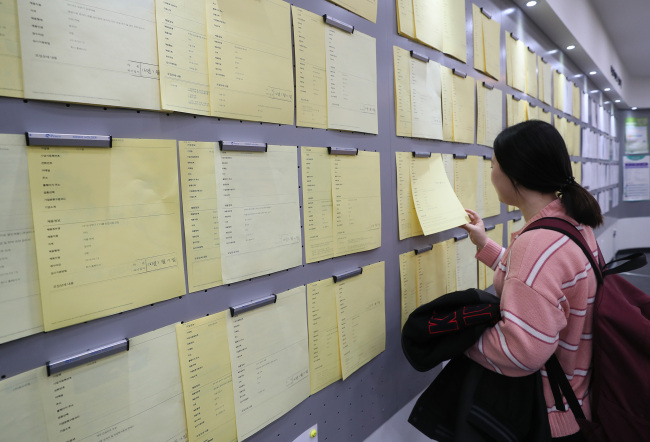

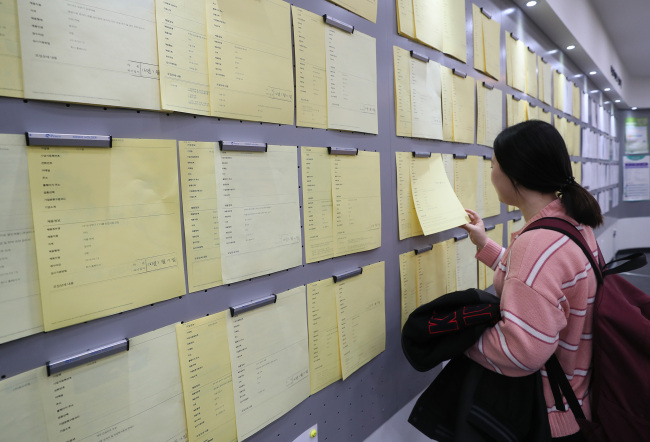

|

(Yonhap) |

The youth unemployment in the country is set to further deteriorate in the coming years, as the population aged 25-29 is projected to grow from 3.28 million in 2016 to 3.67 million in 2021 before beginning to decrease in 2022.

Government officials worry it is only a matter of time before the youth unemployment rate soars above 12 percent, if nothing is done.

They hope the latest measures to boost youth employment will encourage about 200,000 young job seekers to work at SMEs, many of which are suffering from a chronic shortage of manpower.

Presiding over a meeting on job creation last week, Moon said such measures should lead to the creation of stable quality jobs, not short-term ones that would only make the labor market look to be improving on paper.

He also urged the parliament to approve a supplementary budget bill to be submitted by his administration next month to help finance expanded support for employees at SMEs.

But many experts note youth unemployment could hardly be resolved or eased significantly just by increasing fiscal spending.

“The effect of measures to subsidize wages will be limited and unsustainable,” said Sung Tae-yoon, a professor of economics at Yonsei University.

The programs laid out by the government are designed to give entry-level workers at SMEs about 10 million won more in wages, allowances and income tax exemptions annually. But the financial and tax benefits will be put in practice for three to five years.

Doubts have been raised over whether such temporary incentives will be enough to encourage young people to give up efforts to land jobs at large corporations and to work at smaller companies.

Kim Dae-il, a professor of economics at Seoul National University, said there seems to be a serious mismatch between the jobs youths want and the ones the government seeks to support.

Many experts say the Moon administration should focus on reducing the wage gap between small and large companies by helping enhance the competitiveness of SMEs. This would be a more fundamental way to induce young job seekers to work at SMEs.

Official data have shown state-funded job programs have not been as instrumental as expected by policymakers in bolstering employment.

Despite an 11 trillion won extra budget implemented shortly after Moon took office in May to help create more jobs, the on-year increase in the number of employees decreased from 314,000 in September to 257,000 in November and 104,000 last month, according to data from Statistics Korea.

Last month’s figure was the lowest since January 2010 in the wake of a global financial crisis.

Pro-labor steps taken by the Moon administration, which are placing heavier burdens on companies, contradict its efforts toward increasing employment.

Experts estimate local companies will be made to pay trillions of won more in labor costs annually in years to come due to a sharp increase in the minimum wage, reduced work hours and pressures to turn temporary jobs into permanent ones.

Measures to raise the maximum corporate tax rate and cut tax breaks on research and development investment are also set to further increase corporate costs.

The Moon administration has also been criticized for dragging its feet on industrial restructuring, deregulation and labor reforms, which are essential to boosting corporate activity and developing new growth engines.

“Creating more jobs is basically up to companies, not (state-funded) incentives provided to workers,” said Nam Sung-il, a professor of economics at Sogang University.

Concerns are growing that the Moon administration’s policies that have worsened business conditions at home will result in accelerating the exodus of local firms to other countries that are competing to forge a more business-friendly environment.

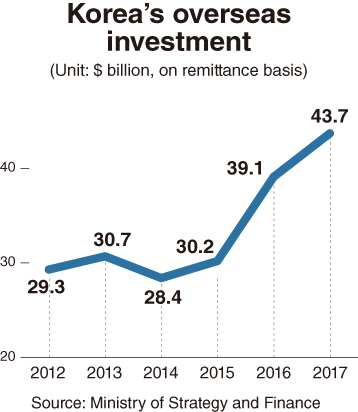

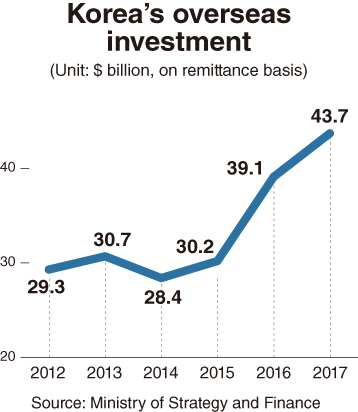

Korea’s overseas direct investment on the basis of remittance increased from $29.3 billion in 2012 to a record high of $43.7 billion in 2017, according to recent data from the Finance Ministry.

Investment by local SMEs abroad more than doubled over the past three years to $7.5 billion last year. The spread of corporate exodus to small and midsized firms deepens concerns that the country will see a continuous worsening of unemployment.

On the contrary, domestic private-sector investment decreased 0.7 percent on-quarter in the final three months of 2017, marking the first negative growth in two years.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)