Calls are rising for South Korea to take full precautions against a possible exodus of foreign capital in the course of tensions escalating over North Korea’s missile and nuclear weapons programs.

Government officials have said the impact of the North Korea risk on the local financial market will be limited. Their measured remarks might be intended to avoid exacerbating volatile market sentiment.

|

(Yonhap) |

But many experts including former economic policymakers worry that the government lacks a sense of crisis in working to contain or limit the fallout from mounting geopolitical risks coupled with deteriorating external trade conditions.

“A highest level of alert is needed to cope with the ongoing situation,” said a former senior economic official, who asked not to be named.

The Korea Development Institute, a state-run think tank, said in a report published last month that North Korea’s development of missile and nuclear capabilities is expected to exert greater impact on the financial market down the road.

The report said the North Korea risk may be the so-called black swan, a high-profile and hard-to-predict event that brings a catastrophic impact.

“It is hard to evaluate the exact level of danger sparked by North Korean provocations based on past experiences,” it noted, cautioning the market may underestimate the growing North Korea risk.

The memory of the foreign exchange crisis that hit South Korea in 1997 was revisited late last month when foreign investors sold off 3 trillion won ($2.64 billion) worth of bonds in just two days and the country’s credit default risk reached a 19-month high.

Volatility in the local financial market seems somewhat subdued this week after the long Chuseok holiday.

The credit default swap premium for South Korea’s foreign exchange stabilization bonds with a five-year maturity stood at 69.9 basis points Friday, down from 74.09 basis points on Sept. 26, the highest since the 78.86 basis points recorded on Feb. 11, 2016.

The CDS spread reflects the cost of hedging credit risks on corporate or sovereign debt.

Foreign investors net purchased more than 800 billion won in South Korean shares Tuesday.

Despite heightened tensions on the peninsula, global rating agencies have kept their ratings on South Korea and outlooks for the country unchanged.

But it is not guaranteed that they will adhere to this stance going forward.

A downgrading of South Korea’s sovereign rating amid a severe intensification of the confrontation between the US and North Korea could risk causing foreign capital to flow out of the local market.

During his visit to the US this week, Finance Minister Kim Dong-yeon plans to meet with officials of the three global rating agencies -- Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch -- for a second time in two weeks to reassure them again of South Korea’s economic fundamentals and ability to cope with possible emergencies.

The country’s economic fundamentals seem more robust than the time when it was engulfed by a foreign exchange crisis two decades ago.

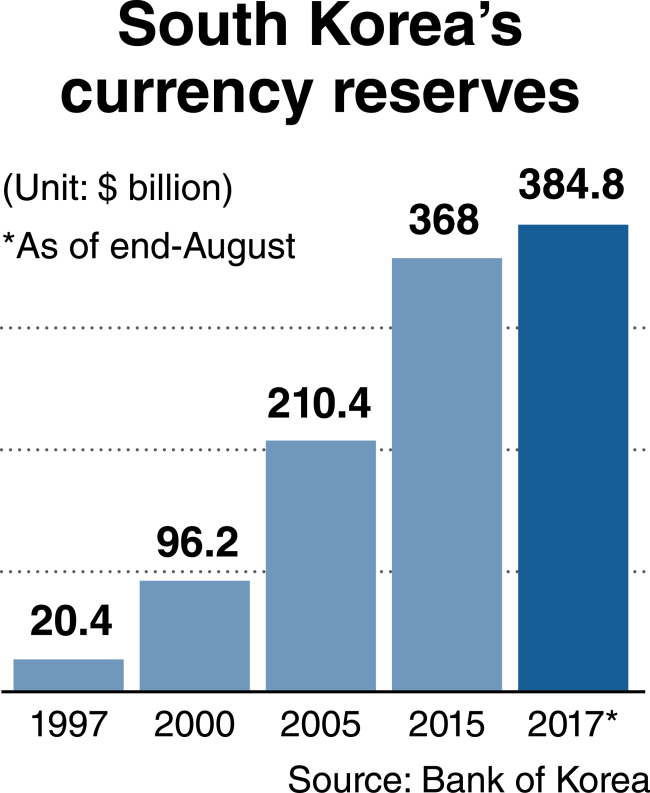

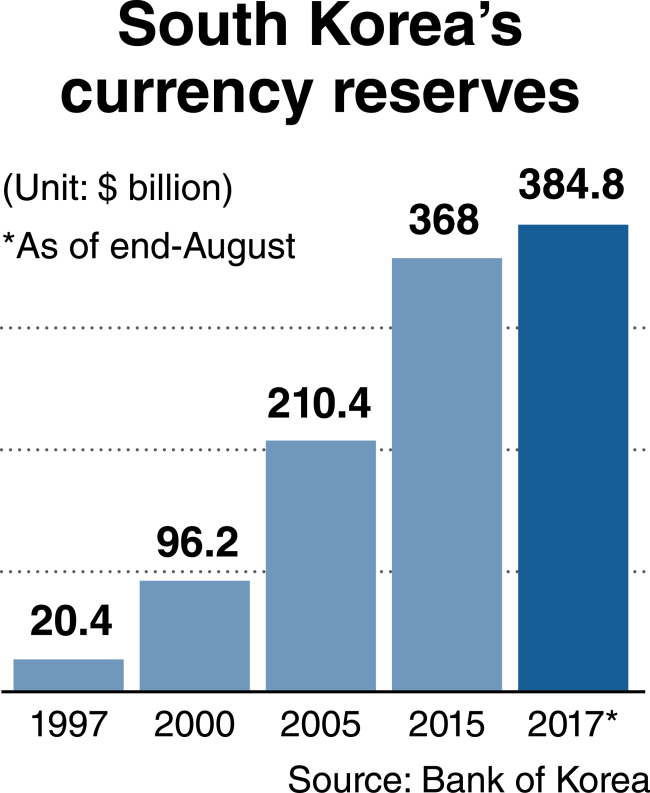

According to data from the Bank of Korea, the country’s foreign reserves stood at $384.8 billion as of August, dwarfing the $20.4 billion at the end of 1997.

The ratio of South Korea’s short-term external debt to its foreign reserves remained at 30.8 percent in June, compared with a whopping 657.9 percent as of end-1997.

The country extended its streak of current account surplus to 66 months in September.

But experts note that as a mid-sized open economy, South Korea cannot be overconfident in its economic fundamentals and ability to deal with possible financial turmoil.

Oh Jung-geun, a professor of IT and finance at Konkuk University in Seoul, estimates South Korea will need approximately $80 billion more than the current currency reserves if it is hit by another foreign exchange crisis.

Expanding currency swap lines with major economic partners is essential to build a stronger fire wall against a possible recurrence of financial turmoil, according to economists and former policymakers.

A currency swap is a tool for guarding against financial turbulence by allowing a country beset by a liquidity crunch to borrow money from other nations with its own currency.

A $30 billion swap deal signed with the US in 2008 helped South Korea overcome a global financial crisis. The accord expired in 2010.

Experts say South Korea should ask the US to conclude a new swap agreement alongside negotiations on the revision of a bilateral free trade pact.

They also raise the need for the country to be more active toward reopening a currency swap line with Japan, which was terminated in 2015.

It is unclear whether South Korea and China will agree to renew a three-year swap arrangement between the two countries, which expired Tuesday, though officials here express guarded optimism.

|

(Yonhap) |

Shin Je-yoon, former head of the Financial Services Commission, stressed the importance of maintaining fiscal soundness as the last line of defense against a possible recurrence of financial turmoil.

South Korea’s national debt increased from 60.3 trillion won in 1997 to 626.9 trillion won last year.

Its national debt-to-GDP ratio still remains below the average of members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. But alarms have been raised about the fastest pace of increase among major advanced economies.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Weekender] Korea's traditional sauce culture gains global recognition](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050153_0.jpg)