|

Balwoo Gonyang’s Head Chef, Kim Ji-young, poses during an interview with The Korea Herald. (Kim Hae-yeon/The Korea Herald) |

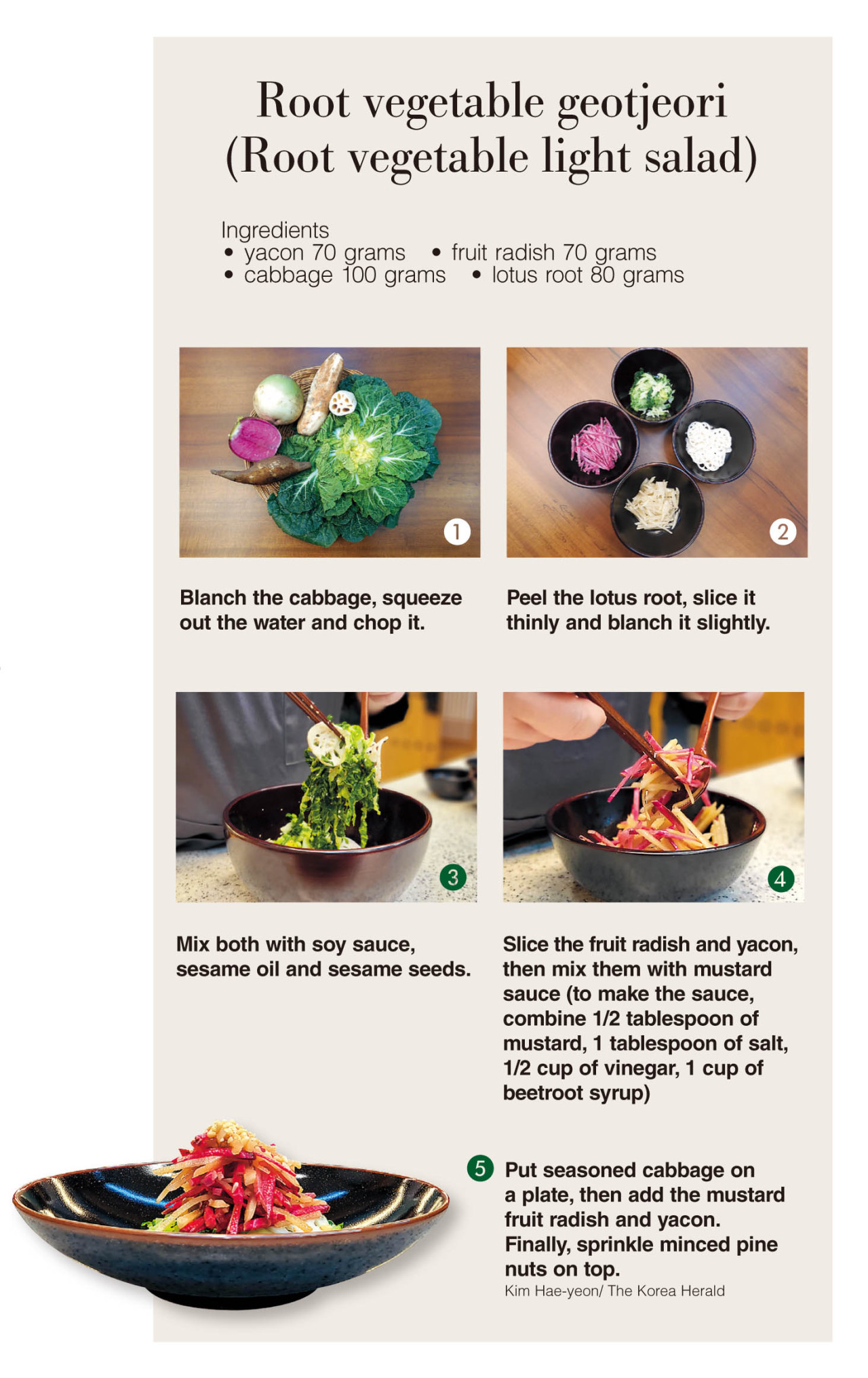

On an early December afternoon, Kim Ji-young, head chef at Balwoo Gongyang, a restaurant dedicated to temple cuisine operated by the Cultural Corps of Korean Buddhism, was demonstrating how to make root vegetable geotjeori, or a light salad of root vegetables. Unrushed and with a generous smile, the chef hummed a tune as she demonstrated the cooking process, step by step.

With 1,700 years of history, some keywords come to mind upon hearing “temple food,” such as vegetarian or slow food. Kim said that the public’s perception of temple food has significantly changed over the past five years from when she first entered the Balwoo Gongyang’s kitchen in 2017.

“The keywords remain similar, but it was not considered a daily meal,” Kim said in an interview with The Korea Herald. “Since temple food is strict with the use of ingredients, the cuisine was thought of as only suitable for religious people or very conscious diners.” Kim mentioned that it took her some time to fall in love with temple food herself.

In her late 20s when she embarked on her career as chef, Kim wasn’t persuaded by her Buddhist mother‘s advice to study temple food. At the time, Kim was looking for trendy foods that easily caught people‘s attention with color and plating techniques. After making her way through French, Japanese and Korean royal cuisines, she made her way to the Ven. Seonjae, a well-known temple food expert whose classes she attended. A year after Kim became the head chef, Balwoo Gongyang earned a Michelin one-star rating.

Kim gradually learned through experience that as more people started to eat for the environment, they began choosing foods that are better for the Earth. Korean temple food came to be recognized as honest comfort food regardless of one’s religious background, according to Kim.

The menu changes four times a year at Balwoo Gongyang, as it operates in accordance with nature‘s order. Since temple food is traditionally consumed by practicing Buddhist monks and nuns, they avoid the use of “o-sinchae,” or five pungent vegetables, known to hinder spiritual practice -- onions, garlic, chives, green onions and leeks. Novice cooks might think that without the five, dishes will be bland. However, Kim says that there are unique scents and tastes in all ingredients, as long as they are fresh and cooked according to their characteristics.

“To present good food to our guests, one philosophy I dearly hold is to find the best seasonal ingredients each year. A habit of mine is to keep a secret notepad, recording up-to-date fresh ingredients after regular visits to traditional markets. I mix them up, and make a creative dish out of those seasonal ingredients.”

When asked about ways for Korean temple cuisine to spread internationally, Kim mentioned an episode with a customer she met in 2018. “He was an exchange student in his 20s from the US. After trying our food, the first thing he said was, ‘It reminds me of my grandma’s cooking.’” Kim later found out that the student’s grandmother was from Eastern Europe, which also has a long history of fermented foods.

Likewise, Kim insists that temple cuisine is not something too exotic or far from reach.

“The roots of temple food are in the state of mind. The underlying spirit is to try to avoid processed food or animal-based meat and oil. If you can’t find traditional Korean pastes, you can find and make your own that fits your local environment,” Kim said. Believing temple cuisine should follow Buddhism’s philosophy of broad tolerance, Kim says the boundaries can be adjusted to local surroundings.

“Protestant pastors come to our restaurant, as well as Catholic nuns and priests. They come to appreciate food grown and made in a healthy environment,” the chef said.

Kim noted that anyone is welcome, as long as they have the spirit and intentions to care about good food.

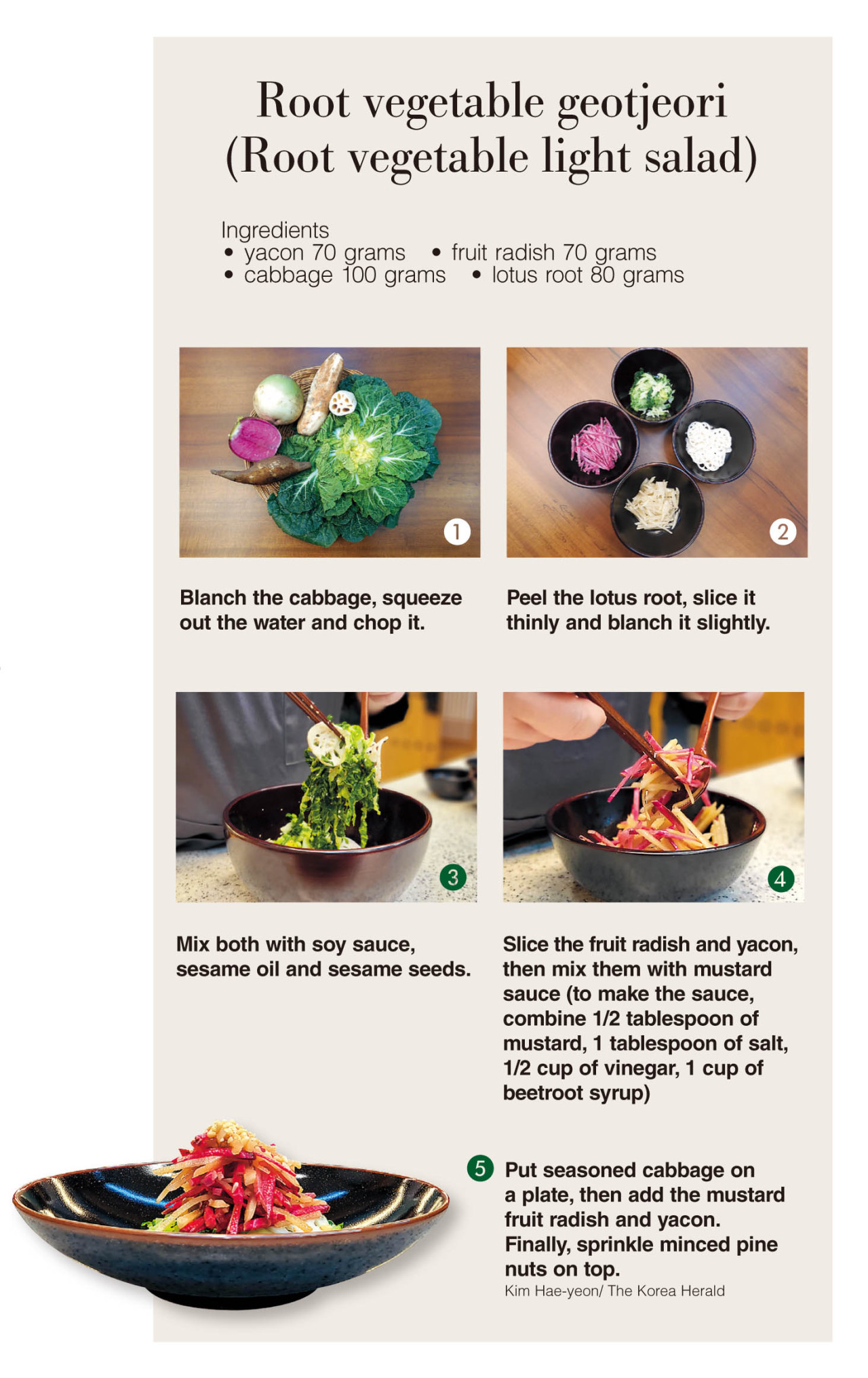

Instructions

1. Blanch the cabbage, squeeze out the water and chop it.

2. Peel the lotus root, slice it thinly and blanch it slightly.

3. Mix both with soy sauce, sesame oil and sesame seeds.

4. Slice the fruit radish and yacon, then mix them with mustard sauce (to make the sauce, combine 1/2 tablespoon of mustard, 1 tablespoon of salt, 1/2 cup of vinegar, 1 cup of beetroot syrup)

5. Put seasoned cabbage on a plate, then add the mustard fruit radish and yacon. Finally, sprinkle minced pine nuts on top.

By Kim Hae-yeon (

hykim@heraldcorp.com)